My experience with Funeral doesn’t begin in 2004. I was, after all, eleven. It begins a half-decade later with the “Wake Up”-scored trailer to Where the Wild Things Are, because even then, I was normie trash.

Wherever and whenever I discovered the song, it inspired me to seek out the rest of the album. Apologies if I get a little navel-gazey here. But maybe that’s the only way to look at Funeral. Music, even more than every other medium, is deeply personal and subjective, and there’s a certain point where, like a good joke, you just have to say you had to be there.

Funeral wasn’t the first “adult” album I sought out on my own. That would be its non-union Mexican equivalent, Coldplay’s Viva La Vida, (which I still have no small fondness for), or even more embarrassingly, the score to mid-tier Alfred Hitchcock comedy The Trouble with Harry. (I liked the opening credits theme, I had an iTunes gift card, and I couldn’t just buy the one track, ok?) But it is the beginning of my mature relationship with music. Funeral made me realize everything music could be and do.

Eleven might not have been the right age for me to discover Funeral, but sixteen absolutely was. This is an album about the bittersweet transition to adulthood, an un-self-conscious work of epic, teenage-scaled emotions. Arcade Fire, with their Wes-Andersonian vintage-chic album art and their lengthy track names, are in the indie hipster scene. But they’re not of it. There’s not a trace of irony here. What you see is what you get. Like any grand display of emotion, it’s easy to laugh at. We remember our teenage emotions, and most of them were, after all, ridiculous. But unlike most of their peers, there’s never any doubt that Arcade Fire are deeply, painfully sincere.

And for all Funeral’s ambitious song suites and fairy-tale imagery, there’s nothing cute or twee about it either. It easily could be, with lyrics referencing the Soviet space dog Laika, or the instrumentals of songs like “Crown of Love,” 21st-century kids putting on the costume of a 19th-century waltz. Some lyrics strain at profundity instead of actually getting there, like when “Power Out” hamfistedly expands its storyline into a grand metaphor: “And the power’s out/In the heart of man./Take it from your heart,/Put in your hand!” Half-heartedly listening to it in the background for the first time in years, I wondered if maybe I’d been wrong — maybe I’d outgrown Funeral and it really was too cute for its own good. But then a track we’ll get into in more depth later cut through me as deeply as it ever did, and the rest clicked back into place. Funeral transcends turn-of-the-millennium trends by sheer force of artistry. It simply is.

If Funeral opened up a new world of music to me, it also closed it. I’ve spent the last decade looking for something else like it, but like so many of the best albums, no such thing exists. Arcade Fire combine rock with an expansive, full-orchestra classical influence to create effects I’ve chased but been unable to find even in full-on classical music. (Wikipedia claims part of the album was recorded in an apartment, and a citation’s never been more needed.) Not even Arcade Fire themselves have been able to recapture Funeral’s magic, and maybe it’s to their credit they haven’t tried. Their later albums foreground the influence of other genres instead: synth, new wave, and even punk, which is about as far from classical as you can get. But it’s part of the strange alchemy of Funeral that those influences are already present here, cellar-rave basslines chugging under soaring strings. It’s hard to call the attitude behind Win Butler’s shout, “You ain’t fooling nobody!/The lights are out!” on “Power Out” anything but punk.

The nearest ancestor to his odd off-kilter yelp isn’t in anything classically beautiful or even in the prog-rock maestros who dabbled in the same influences, but Talking Heads’ David Byrne. Some deliveries, like “He tore images/Out of his pictures” on “Laika” edge right up to impersonation. But the effect is totally different. Byrne always seems like a strange, unearthly visitor floating above his material with arch distance, even, if a recently-resurfaced story from Brian Eno can be believed, in real life. Win twists his vocal stylings into something unbearably emotional — not a man putting on a voice, but a voice unwillingly distorted by almost physical pain, an unaffected affect. He makes use of Byrne’s trademark whoop too, but he pitches it higher, almost a whimper, and in Butler’s hands, it becomes less an expression of the joy of rocking than deeper, darker emotions.

Funeral isn’t quite a concept album in the Tommy/The Wall sense. But there’s a loose plot of children trapped in a Canadian snowfall, mostly running through the helpfully numbered “Neighborhood” suite, though it’s just as easy to envision “Rebellion (Lies)” taking place in a power outage-induced sleepover. (And I have to wonder if this album would have burrowed so deeply into my subconscious if I hadn’t discovered it during an equally harsh Montana winter.) There are more intangible narratives running through Funeral as well: the universal ones of growing up and, as you’d expect from the title, loss and death. It’s heavy stuff for a debut album, but Arcade Fire came by it honestly: there were famously several deaths in the band’s collective family during the album’s production, and sideman Régine Chassagne draws from the true stories of her parents’ exile and death when she takes the lead on “Haiti” and “In the Backseat.”

But it keeps the harsh stuff in reserve at first. It opens with the ethereal tinkling and wheezing of an apparently very old piano and the fairy tale story of “Neighborhood #1 (Tunnels).” Snow burying the neighborhood isn’t yet a threat but a fantasy, allowing a child to imagine digging a tunnel to his lover’s window and running away together like a Northern-Hemisphere Tarzan and Jane. But like the best fairy tales, it doesn’t hide the dark undercurrents. It’s nakedly a story of escapism from the suffering of reality: the narrator plans to dig the tunnel “When/My parents start crying.” And the responsibility he dreams of running away from hangs heavy over his dream. Win closes the Edenic fantasy by screaming, his voice distorted by pain as much as by the lo-fi recording,

Sometimes

We remember our bedrooms

And our parents’ bedrooms

And the bedrooms of our friends.

Then we think of our parents.

Whatever happened to them?

But here, as in all of Funeral, the beauty sits alongside the horror, created by the unlikely push-pull of classical and rock, an orchestra’s worth of instruments rising higher and higher and a fuzzed-out guitar coming back down, and Régine’s unearthly, averbal cooing, unclassifiable as either.

I didn’t know what to make of that push and pull as a teenager. The world’s youngest codger, I believed that art’s purpose was to capture a certain narrowly, classically defined image of beauty. In that very teenage way, inarticulate but believing religiously in my own articulateness, I thought, “Sometimes it’s more than just music, but sometimes it’s less.” Arcade Fire understood what I didn’t, that art should capture the full spectrum of life and that musicians need harsh sounds to express harsh emotions: the squealing violins in “Power Out,” the clang of guitar strings in “In the Backseat.” For all their classical influence, Win and Régine are far from classically trained vocalists, but every time they go off-key it reflects the dissonance of their experience. Every time they go beyond their range, they understand Brian Eno’s lesson that “the blues singer with the cracked voice is the sound of an emotional cry too powerful for the throat that releases it.” A smooth, perfect voice has a more limited range. It can’t handle the sound of choked-back sobs or the rasp of impotent rage that Win can.

The beauty that is here, and there’s plenty, is of the kind C.S. Lewis described to promote his friend Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings: the kind that “pierces like cold iron” and “breaks your heart.” Someone once told me their class sang “Wake Up” at graduation, and I wondered if they realized how dark the words in their mouths were. Lyrics about “turning every good thing to dust” and hearts getting torn up didn’t seem appropriate for a celebration.

But maybe the truth is somewhere in the middle. If Funeral is a concept album, it’s united by a unique, ineffable mood, something like ecstatic sadness. Maybe The Wake would have been a better title. That ecstasy’s there even in the dourest, dirgiest songs, like “Un Année Sans Lumiére” and “Crown of Love,” where it almost seems like the band’s been bottling up its energy and finally can’t resist releasing it for a kind of dance break at the end. And in “Crown of Love,” there’s another beauty like cold iron as Régine’s falsetto pierces through the instrumentals.

I almost said “despair” instead of “sadness,” but if anything, it’s the opposite. Hope, or at least yearning, saturates everything, as the vocals and other instruments keep straining for higher and higher notes, as if they were reaching for something. Or maybe hope is embodied in the music itself. The city may be dark, but we can still dance under the police disco light.

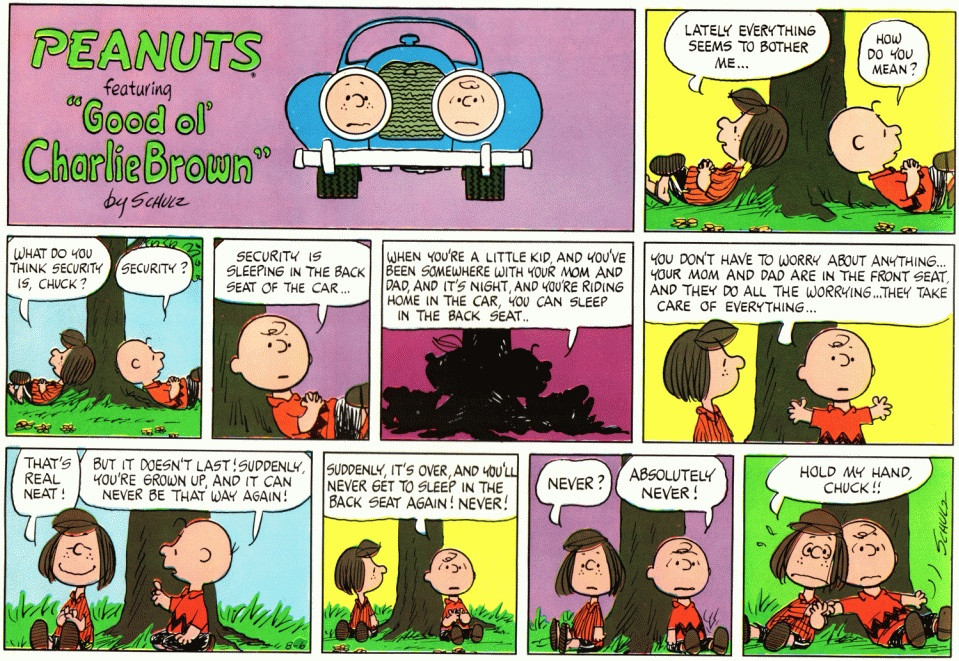

I don’t know if Arcade Fire had this cartoon in mind when they closed the album with “In the Backseat.” I don’t even know if they’ve ever seen it. But its image of the hope and terror of growing up does a lot to explain why the song resonates so strongly with me. If music is subjective, that might explain why, in all the praise of Funeral as a whole, the song I still believe is the greatest and saddest ever recorded seems to be overlooked. In their survey of what they claim are “Thousands of critics’ lists,” Acclaimedmusic.net found plenty that were willing to honor Funeral and individual tracks like “Wake Up” and “Rebellion (Lies).” But even in a list of 10,000 songs, “In the Backseat” didn’t make the cut.

It starts with that same piano, somehow airily high-pitched and deeply resonant all at once, that opened the album. When the vocals come in, they don’t come from Win Butler but Régine Chassagne, a backup singer taking the foreground for only the second time on the album. Like Win, her weak, trembling voice isn’t great by any classical or technical standard. And it doesn’t matter, because the voice, like every tool, matters less than how you use it. And she uses her weaknesses to create an aching, open-wound vulnerability that’s far stronger than anything any vocalist I’ve ever heard has accomplished. But when she needs to bring the power, she does, ending the song with a banshee wail she holds for an almost superhuman length. It conveys more emotion in two wordless syllables than a thousand words ever could. And if her untrained lungs aren’t quite up to it, that rasp of physical pain only doubles the emotional pain.

That pain is bone-deep. It’s not just the romantic ups and downs that most pop music mines for material but death, the ultimate breakup. That’s about as universal as an experience can be, but Régine’s pain is both personal and specific. She even calls her mother, Alice, by name.

There are other, subtler pains running through the song too, like the pain of growing up. As in so much great music, it’s represented by “learning to drive.” But this isn’t Springsteen-style joyriding. This is the kind of maturity that’s not grown into but forced upon you. There’s no one to tell you what to do, but also no one to provide for you — in this case, because they’re no longer there. “In the Backseat” follows “Rebellion (Lies),” a song asking what to do when we learn our parents have lied to us. “Backseat” follows it up with a more difficult question: What do we do when we’ve exposed the biggest lie of all, that they’d always be there for us?

Let’s go back to 2009. Like Régine, I was learning to drive. Hyperaware of the danger, maybe more than actually existed, I felt like I was taking my life in my hands in more ways than one. And for one reason and another, it wasn’t going well. I couldn’t practice out of class without having to navigate the extra dimension of my parents’ manual transmission. (In the interest of not being any more woe-is-me than necessary, my parents actually bought me a car of my own a year or two later.) And I’ve learned since then that my autism meant I needed three or four times the practice my peers did. Not that they would have cared if they’d known; as it was, they never let up on me about it.

Alice didn’t die in the night, but my teacher dropped dead in the middle of class. (And it didn’t help me any that my parents both independently jumped to the conclusion I’d scared him to death in the car.) For me, driving was a source of anxiety instead of a release from it, and a series of accidents later on did nothing to shake that impression. It’s only in the last few years that I’ve learned to look at it from the Springsteen side — to find the peace in the frontseat.

With Funeral’s fifteenth anniversary last year, there were several attempts to tie it into the zeitgeist: the handover of indie rock from grungy headbangers to trendy granola hipsters, or the global anxieties of the War on Terror. But I think “In the Backseat” tells the truer story. As the Funeral generation, the first since the Depression to be worse off than their parents, has grown up, that anxiety of leaving the backseat has defined us. What “adulting” jokes hide and cope with through comedy, Funeral screams out as tragedy. It’s the pain of being promised the world only to have the world take far more than it gives — now more than ever that we’re surviving a global plague caused by adult incompetence, one that’s set to plunge us into another recession before we’ve had time to recover from the last one. In the song’s metaphor, it’s finding the car’s brakelines were cut once it was our turn to drive.

Arcade Fire’s songs about the “kids” are anthems for a Peter Pan generation that didn’t “grow up/Our bodies get bigger but our/Hearts get torn up.” So much of the response to this strange, broken world we’ve inherited is to retreat into infantilization, to hide from the adult world by sitting and watching Rugrats tapes in Spongebob pajamas. But I think Funeral’s smarter than that. Unwanted independence is still independence and unwanted freedom is still freedom. “Alice died/In the night,” Régine sings. “All my life/I’ve been learning to drive.” There’s sadness there, juxtaposing adulthood and loss. But it’s ecstatic sadness. Childhood’s lost, but adulthood’s gained. And that ecstasy reaches into Régine’s anguished howl too. It’s pained. But it’s also triumphant. That’s the album in a nutshell: we may be at a funeral, but at least we’re not in the casket. And that’s something to celebrate, however briefly that lasts.