Doug’s Cinematic Firsties is a recurring series wherein Douglas Laman (A.K.A. NerdInTheBasement) will review a well-known classic motion picture that he’s never seen before.

When Todd Haynes goes to the 1950s, you better expect some remarkable cinema. Haynes is already a great filmmaker on his own merits but just like with Martin Scorsese doing religious-themed cinema or Agnes Varda doing intimate movies about the virtues of everyday people, dramas exploring issues relating to identity in the 1950’s bring out the very best in Haynes. Much like Spike Lee’s BlacKkKlansman, Haynes doesn’t use period pieces to make the suffering of the marginalized a thing of the distant past for privileged viewers. Instead, both BlacKkKlansman and the Todd Haynes directorial effort Far From Heaven (the latter being the subject of this review) intend to make one contemplate how the horrors of the past reverberate into the modern-day world.

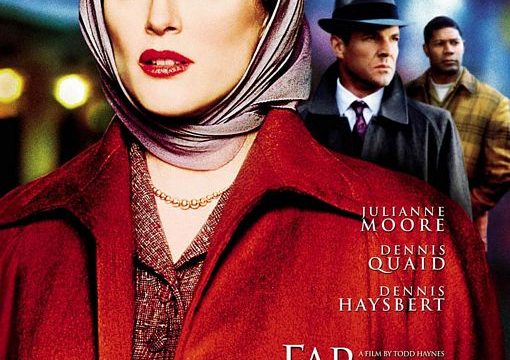

The lead character of this piece is Cathy Whitaker (Julianne Moore), who is living the perfect life for a housewife in Connecticut in the 1950’s. She’s got a husband, Frank Whitaker (Dennis Quaid), who has a steady job, two wonderful kids, a wonderful house, things couldn’t be more perfect! Well, that whole existence gets upended once she stumbles on Frank kissing a male co-worker at his work. At the same time she realizes how distant she is from the husband she thought she knew, Cathy begins to strike up a friendship with her family’s new gardener, Raymond Deagan (Dennis Haysbert). Here’s somebody Cathy actually begins to connect to on a profound level. Too bad her Connecticut neighbors disapprove of this friendship in no uncertain terms.

Movies that are set in the 1950s dealing with the bigotry of the era hiding under a guise of white picket fences and happy-go-lucky attitudes isn’t exactly a new proposition. However, Far From Heaven is unique in its depiction of how and where prejudice emerges in this period-era society. Specifically, it comes from people films don’t usually code as narrow-minded. These are upper-crust people from Connecticut who proudly say they’re all for the advancement of people of color but get squeamish about the idea of actually interesting with non-white people. Carey Whitaker and her neighbors are basically the kinds of people who, if they lived in 2016, would have voted for Obama a third time if they could.

Even authority figures can’t be trusted, like a doctor who, upon noting to Frank that he has “more modern approaches to homosexuality”, proceeds to suggest electric shock-therapy to treat Frank’s queerness. Haynes’ script constantly finds thought-provoking ways to manifest prejudice in the world of Far From Heaven and similarly omnipresent is Far From Heaven’s adherence to certain traits of Hayes Code era American cinema. Transitions between scenes, for instance, use the same kind of editing techniques that ran rampant in classic Hollywood films while the production design & costumes are clearly hewing closely to the extravagant colorfulness of a filmmaker whose presence is felt throughout Far From Heaven, Douglas Sirk.

Perhaps most interesting is that characters speak in a style reminiscent of films from this period of Hollywood’s history. Specifically, there’s little to no swearing to be found, references to sex are kept to vague references (Cathy and her friends talking about how often they “do it” with their husbands is about as explicit as it gets), why, Cathy’s son even expresses disdain by saying phrases like “Aw jeez!” An honest-to-God wonder why Haynes didn’t go whole-hog and have this adolescent character exclaim “Leaping Lizards!” in a moment of excitement. The film’s sole F-bomb, emerging from Frank after his first doctor visit, intentionally is framed as an accident, a depiction of just how rattled Frank is about coming to terms with his sexuality.

That moment of extreme profanity demonstrates how Far From Heaven frequently embraces Hayes Code-era restrictions on what can and cannot be said or shown on-screen as a way of demonstrating how stifled members of marginalized communities are in the world. Just as characters in Hayes Code era cinema couldn’t talk about interracial marriage or homosexuality, so too are people of color or queer people frequently forbidden to express their own viewpoints publically for fear of alienating privileged members of society. This brilliant use of Hayes Code-era restrictions demonstrates that Far From Heaven has as much of an impressive knowledge of film history as it does with real-world subjugation of vulnerable populations. Another way Far From Heaven uses Hayes Code era restrictions to its advantage is in how it establishes a world as one firmly rooted in a 1950’s era of Hollywood filmmaking before taking its characters and their world into a far more thematically complex direction than you’d find in your average Hayes Code film.

This aspect of the production is perfectly embodied by Julianne Moore’s lead performance, which at first captures the archetypical 1950’s housewife in astonishingly accurate detail. The way Moore composes her slightest hand gesture makes it look like Cathy Whitaker is constantly preparing to pose on a publication like Housewife Monthly. But when it comes time for a greater level of nuance to be introduced into the character, well, Moore is more than up to the task. Moore is especially adept at poignantly capturing Whitaker coming to terms with how the world around her is far more complex than she could have ever imagined. She’s similarly excellent in her intimate scenes with Dennis Haysbert’s Raymond Deagan, the two have such quietly touching chemistry together as they find comfort just in being able to share in each other’s company. Just as remarkable as Moore is Haysbert in a performance that really makes me wish Hollywood would give him more chances as a lead performer. Haysbert’s does great work in making sure Deagan isn’t just around to support Whitaker’s storyline, Haysbert gives the character his own distinct complex personality that truly touches your heart.

Just as impressive as the performances is Far From Heaven’s wonderful production design. As previously mentioned, this is a project taking some heavy-duty cues from Douglas Sirk films which were famous for their gorgeous sets. Similarly, Far From Heaven doesn’t skimp on the stunning locales, with the Whitaker household, in particular, being an avalanche of colorfully gorgeous locations. This movie isn’t just content to lean on homages to prior films, though, Far From Heaven also brings plenty of its own unique visual qualities to the table, including in the recurring use of green as well as how exterior locations tinged with colors associated with Autumn and Winter manage to conjure up an appropriately melancholy feeling in the viewers’ stomach. Much like the 2015 Todd Haynes masterpiece Carol, Far From Heaven is a visually masterful production that delves into the 1950s to create far more thoughtful and emotionally resonant cinema than your average Hollywood mid-20th century period piece.