If there is one piece of received thinking about film that ought to be challenged, it is that there is somehow a positive correlation between popular success and artistic quality. Yet there are multiple examples of works of art that were deemed unpopular (or worse) at their premiere and have gone on to have lasting value. With that, comes a cinematic lesson from the 1980s.

Part 2: “Love Is a High-Wire Act”

One from the Heart (dir. Coppola 1982)

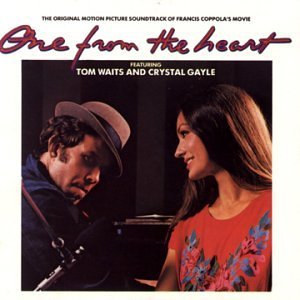

Before reading further, you should take the opportunity to listen to Tom Waits’s soundtrack to One from the Heart (on vinyl, because to my ears, it sounds best). Not only are the songs remarkably lyrical depictions of the peaks and valleys of romance; they are also filled with stately arrangements and subtle, yet gripping, musical hooks. These songs pay tribute to the sophisticated pop of the 1930s. For example, as Barney Hoskyns observes in Lowside of the Road: A Life of Tom Waits (2009), the wordplay of “Is There Any Way out of This Dream?” could have been lifted from Cole Porter.

It would be increasingly rare to hear this kind of music in a Hollywood film in the 1980s: the sonic barrage of “What a Feeling” and “Maniac” from Flashdance, released just one year later in 1983, would open the gates to brash, insistent soundtracks, sporting songs with huge choruses, layers of synthesizers, drum machines, and guitars that sound like they’re being played through stacks of cranked-up amplifiers (though, the guitars are actually being played through electronic effects devices that duplicate the arena-rock sound).

Even with their homage to a classic songwriting style, Waits’s songs have a raw, emotional honesty, not at all hesitant to dwell for minutes at a time on the carnage inflicted by heartbreak that is intensified by resentment and regret. That simply cannot be said of post-Flashdance soundtracks, for they are glossy and smoothed out—they have the anesthetized sensation of a cocaine high (the drug du jour at the time).

The narrative analogue for these soundtracks is the “high concept” style that films such as Flashdance initiated in the 1980s. Quoted in Peter Biskind’s Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How the Sex-Drugs-and-Rock ‘N’ Roll Generation Saved Hollywood (1998), Steven Spielberg described such a style as: “If a person can tell me the idea in twenty-five words or less, it’s going to make a pretty good movie. I like ideas, especially movie ideas that you can hold in your hand.”

Francis Ford Coppola went in the opposite artistic direction by intending his film to convey multiple narrative perspectives. In addition to the action taking place on the streets of Las Vegas, as Hoskyns points out, Coppola “wanted to make the film as a kind of musical, with a male and female voice representing the thoughts and feelings of his characters—like Zeus and Hera looking down on the romantic struggles of foolish mortals.” Waits voiced the male perspective, while Crystal Gayle voiced the female perspective.

Additionally, Coppola envisioned the film as the start of a larger, more ambitious project, using his newly-acquired studio (at considerable financial risk), Zoetrope, to create, independently of the Hollywood system, “live cinema”: what he described in the DVD commentary track as using video technology to combine the intimacy and excitement of theater with the visual beauty of cinema.

And, it should crucially be pointed out that Zoetrope was getting off the ground just as the Hollywood balance of power was shifting away from the director (who tended to be viewed, a decade earlier, as the creative mastermind, or auteur) and back to producers, studio executives, and stars. The list of 1980s Hollywood movers and shakers would predictably read: Simpson and Bruckheimer, Cruise, Murphy, Kassar, Schwarzenegger.

In every way, Coppola’s film was an artistic gamble—using a bona fide cult musical artist, Waits, to musically guide the narrative of the film, which was, shaped by the Las Vegas setting, about the gamble of love. But the consensus, historically, is that the film was a massive failure. One from the Heart was pulled from the theaters after seven weeks. Then, the primary loan for Zoetrope was called in, causing Coppola’s financial devastation. Artistically, the film was judged to have failed to deliver on its promise. Even Hoskyns, sympathetic to those artists who buck the system, delivered a rather harsh verdict on Coppola: “With all his highfalutin ideas about synthesizing cinema, theatre, and music, at the end of the day he was just a moviemaker and couldn’t make this stuff work on screen.”

As I re-view this film, two things should be kept in mind, which did not factor in the disastrous screenings in 1982. One, the Waits soundtrack came out afterwards, giving the audience at the time little chance to assess, as I will, the importance of the music to the narrative. Two, the film on DVD (2012) from which I draw my conclusions was reedited. Coppola, as he explained on the commentary track, added a brief comic scene that lightens the tone at the beginning and re-arranged the central dance sequence.

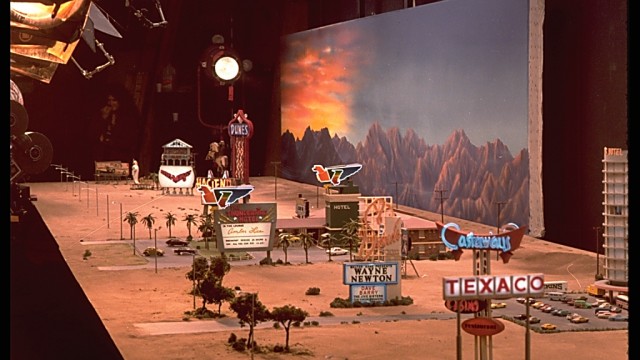

Because the film looks so striking—using careful and complex lighting arrangements to connect color and mood: red for the flamboyant Frannie (Teri Garr) and green for the more down-to-earth Hank (Frederic Forrest)—the first point that should be brought to attention is that Coppola achieved, before digital effects and CGI, a visual look that deserves praise just for its working out of numerous first-generation technological problems, albeit with excessive time, cost, and labor. For example, as Coppola pointed out on the commentary track, he filmed on set at Zoetrope (which constituted a substantial financial outlay), rather than on location in Las Vegas, because he wanted to have the neon lights in full view, whereas in the real-life city it would be impossible because the neon lights are several stories above the street. By way of a useful comparison, this effect is pulled off more easily in the film made, in the digital-era, of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998) in the scene where a car drives down the street with a wall of neon lights as a backdrop that appears to descend from the top of the frame.

The film, as it reflects Coppola’s ambitions for Zoetrope as a factory for a brand-new dream, accordingly comments, from an outside perspective, on the lifelessness and unoriginality of the Hollywood system (which Coppola, at the time, thought was doomed to extinction). As Biskind remarks, the high-concept trend would turn 1980s Hollywood into even more of an echo chamber, making the production of sequels and look-alike films into standard practice. And Hollywood, Coppola seems to realize, is the filmmaking double of Las Vegas, seen as, the way that Hunter S. Thompson famously did in his doom-laden chronicle, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1971), the death of the American dream that hides under the glitter, excess, and money-grubbing. If Las Vegas exacts a financial toll, Hollywood exacts a psychic one, both attempting to satiate more deeply-felt desires for personal and social connection—desires further corroded, as we see in the film, by male jealousy that isolates people and cuts them off from each other.

To put it another way, all of this can be summed up by Steely Dan’s “Show Biz Kids” (1973): the tape loop of “Go to Lost Wages” throughout the song reiterates the hipster putdown of Las Vegas; sarcasm morphs into outrage, directed at Hollywood, in the last verse:

Show biz kids making movies

of themselves you know they

don’t give a fuck about anybody else(part of this lyric was digitally sampled in Super Furry Animals’ “The Man Don’t Give a Fuck,” released in 1996).

Coppola proposed to leave the show biz kids behind by envisioning the future of filmmaking in its past origins in live theater, regarded, idealistically, as a more democratic art form. The horizon line gives the film a flatness that reminds us that it is taking place on a soundstage. Set over the Fourth of July, One from the Heart tells a classically American story about Frannie and Hank, who break up, each then having a one-night affair, and reunite. While the parallel stories and the intense depiction of male jealousy appear derived from the ground-breaking independent film, Faces (1968), directed by John Cassavetes, the use of music furthers Coppola’s intention, as he elaborates on the commentary track, to experiment with different ways of storytelling, for instance, having characters act, without speaking, to the songs. A scene where Frannie wanders through her bedroom, set to “Old Boyfriends,” followed by Hank’s wandering through a junkyard, set to “Broken Bicycles” provides a sense of history to these characters (augmenting the rather thin storyline) and shows them evocatively lost in space, without a firm sense of direction as they are pulled back into their routine lives. The way the atmospheric setting speaks through the actors would be repeated in Paris, Texas (1984), directed by Wim Wenders and starring Harry Dean Stanton, who here plays a supporting role as Hank’s best friend, Moe. In a central example of the democratic approach to storytelling in One from the Heart, Moe has the crucial line in an exchange among him, Hank, and Leila (Nastassja Kinski), Hank’s dream lover for the night:

L: When you love a married man, you have to learn.

H: I’m not a married man.

L: Yeah? You step out there together, but you gotta come back alone. It’s a high-wire act.

M: Yeah. Right. Love is a high-wire act, especially with this guy.

The film, granted, is also a high-wire act. It attempts to balance naturalistic acting, especially Forrest’s Brando-like delivery, with the retro-futuristic setting of a Las Vegas romance. While, at times, the simplified gestures—again epitomized by Forrest, who plays the self-destructive, jealous male to the hilt—work well with the widescreen emotional charge of Waits’s songs, the film’s ending cannot help but feel like a letdown.

This happens, I would say, because the visual narrative simply cannot equal the fluidity and power of Waits’s finest songs, “This One’s from the Heart” and “Take Me Home,” that end the soundtrack and film—and two of the finest songs, arguably, in this phase of his career: the soundtrack brings to a close his being an innovative singer-songwriter (subsequent albums would sharply veer away from this genre and plunge into much greater dissonance and noise). As Coppola states on the commentary, because cameras, before the digital age, could film only for a limited time, he backed away from his original idea to feature continuous action. In the last scene, Frannie returns from out of the frame, as if she just suddenly appeared.

Another way to look at it is that the fall from the high wire is inevitable due to the conventions of a happy ending, which leaves us to face a grimmer reality outside of the theater, or our viewing room. Whatever magic there is can never, of course, last. Somewhat ironically, Coppola’s film, usually regarded as excessive, leaves us wanting more. It is yet another parallel with Las Vegas, or with any vacation destination (and what is film traditionally seen as offering if not a vacation for a few hours?).

It is the same question posed, earlier in the film, by the title of Waits’s darkly humorous song, “Is There Any Way out of This Dream?”, and the lyrics which, in the context of the film’s storyline, serve to comment on the tired fantasies of Hollywood that Coppola tried so hard to dismantle:

let’s take a hammer to it

there’s no glamour in it

If we take Coppola’s ambitions seriously when he made this film (leaving it to the viewer’s discretion whether such ambitions were brave or foolish), then we might conclude that what he finally discovered was that the Hollywood system cannot be completely de-mystified. Just as One from the Heart reproduces a Hollywood ending, so did Zoetrope prove just as costly and inefficient as a Hollywood studio. Another way of putting this is what Hank, in the film, tells Frannie: “You’re always talking about paradise, but when you get there, it’s still gonna be you and all your shit walking along the beach.” For Coppola, the kind of forward thinking that inspired One from the Heart and Zoetrope all but guaranteed (for any number of reasons) that neither would succeed financially.

Coppola’s challenge, issued in his film, to break out of routine might even be interpreted as a call to action for 1980s filmmakers who faced off against Hollywood high-concept filmmaking. Released in the same year, Smithereens (1982), directed by Susan Seidelman, critically reflected on the New York punk music scene’s failure to provide a viable alternative to a less stultified way of living. Furthermore, Coppola’s emphasis on personal storytelling would be taken up, two years later, by Stranger than Paradise (1984), directed by Jim Jarmusch, featuring closed-off characters who say little, set to an off-kilter musical score that at times is reminiscent of Waits’s “The Tango/Circus Girl” from the soundtrack of One from the Heart. Echoing Hank’s remark to Frannie, the main idea of Stranger than Paradise and, similar to Coppola’s film, its questioning of the distinctions between the familiar and unfamiliar is voiced by Eddie, one of the protagonists: “You know, it’s funny… you come to someplace new, an’… and everything looks just the same.”