I find it hard to tell you,

I find it hard to take.

When people run in circles,

It’s a very very

Mad world.

– Tears for Fears

Koyaanisqatsi may be the most awesome movie ever made. Not in the colloquial, surfer-dude sense, though – in the older sense, the sense of inspiring wonder and terror. That’s true for both the things director Godfrey Reggio admires and the things he abhors – for the sweeping helicopter shots of vast, empty landscapes and skyscapes, and for the maddening, sprawling rat race of the “life out of balance” that gives the film its Hopi-language title. Roger Ebert says it best: “All of the images in this movie are beautiful, even the images of man despoiling the environment.” I spent most of my first viewing, even on a tiny laptop screen, with my jaw on the floor.

The prelapsarian prologue, with its scenes of clouds the size of cities (Reggio even thoughtfully provides a city for comparison later) churning and roiling over the mountains, actually makes it easier to understand why humanity would want to lose its connection to nature and rush around to distract from its own insignificance. There’s a surprising amount of explosions in Koyaanisqatsi for such an action-light film. But even the mushroom cloud of an atomic bomb test looks puny and pathetic next to those moving mountains.

Though he gave the film a thumbs-up, Ebert, as you might expect for a Chicago boy, wasn’t a fan of Koyaanisqatsi’s anti-modernist, anti-urban message. “Reggio seemed to think that man himself is some kind of virus infecting the planet,” he says in his review of the sequel Powaqqatsi (and we’ll get to that mess later), “That we would enjoy Earth more, in other words, if we weren’t here.” But it’s not quite as simple as that. Reggio is certainly anti- those other things, but I don’t see him as anti-humanist. He spends a good amount of time focused on human faces, some defeated, and others defiant. It’s hard to see the images of women staring straight into the camera as the blur of a train whooshes by behind them as anything but a tribute to the human spirit. They can be sublime, or they can be ridiculous, like the poor little old man who has to shave in the middle of the street because he didn’t have time at home.

And if all this sounds like simplistic ludditism, it’s worth remembering that Koyaanisqatsi gains so much of its power from the skillful use of technology. The whole medium of film is a piece of postindustrial tech, of course, but this specific film wouldn’t work if it wasn’t also state-of-the-art, with those breathtaking aerial shots and the groundbreaking time-lapse photography that turns the sky into an ocean and freeway traffic into lightning bolts. Koyaanisqatsi is great because it reveals truths about the world we live in by showing it from perspectives we’ve never seen before. Look at its scenes of building demolitions: in slow motion, the tenements look less like they’re being destroyed and more like they’re sagging or melting like the Wicked Witch of the West. From a God’s eye view, the crowds of overstuffed cities seem to be churning in an individuality-consuming mass like those rushing clouds. And you can see a society both too chaotic and too ordered, with the regimented stop-start of traffic, for its own good. We can see people in the train station assert their individuality by stepping out of the crowd to connect with another individual, and then get swept away in the sea of other people like drowning men. Traffic on the interstate or a subway terminal may not actually be the way Reggio shows it, but he jerry-rigs the camera to show how it feels instead. In this life-out-of-balance, even people’s relaxation is exhausting, represented by sped-up footage of channel surfing, shopping, and seizure-inducing video games.

Koyaanisqatsi is a strange beast – too much documentary footage to be a narrative film, too little narrative to be a documentary, too accessible to be avant-garde. The closest thing I can think of Dziga Vertov’s silent film The Man with the Movie Camera, which inspired its own genre of “city symphony” films. The main difference is Reggio came to bury the industrialized world, and Vertov came to praise it. (I’d argue Vertov accidentally ended up proving Reggio’s point, but that’s another discussion for another time.)

If you really want to appreciate Koyaanisqatsi’s singular achievement, all you have to do is compare it to Reggio’s own failed attempts to replicate it. Because the Qatsi trilogy is a case of diminishing returns the most disappointing of action franchises could only dream of. I was thrilled to discover Powaqqatsi on the shelf at my local university’s library. And then I actually sat down and watched it. I was less and less thrilled the longer it went on. How could Reggio follow up one of my favorite movie experiences with (as anyone following me on letterboxd will know) one of the few I willingly watched that I could bring myself to actively dislike?

The biggest difference is that where Koyaanisqatsi makes us see the world like we never have before, Powaqqatsi and Naqoyqatsi show us what we’ve already seen a million times. Despite its pretensions to examine western industry’s “parasitic way of life” and its effect on the rest of the world, Powaqqatsi ends up just being a glorified National Geographic special; Naqoyqatsi, meanwhile, looks like the computer graphics one of those specials might have had in its opening credits sometime in the nineties. Once again proving his willingness to embrace technology and his complete misunderstanding of what made Koyaanisqatsi work, Reggio only used, according to Wikipedia, 20% original footage. Instead, he manipulated and combined existing images into what he called a new “digital cinema.” In practice, that just means a lot of crummy animation and filters on everything. It all looks like the work of a kid who just discovered After Effects.

Powaqqatsi’s National Geographic vibe is just a symptom of the deeper problem. In Koyaanisqatsi, Reggio follows the internet’s cherished advice to “stay in your lane.” An American born and raised, he knew about life out of balance. He’s lived it. And for most of the film, he stays within his homeland’s borders. Powaqqatsi is a confused mish-mash of nearly every place on earth. Without that lived experience, Reggio falls back on condescending clichés about traditional ways of life under threat and laughing native children. He’s out of his depth, and his perspective is appropriately shallow. And yes, there is a lot of irony in a film about the effects of western imperialism that falls back on stereotypes from the imperial age.

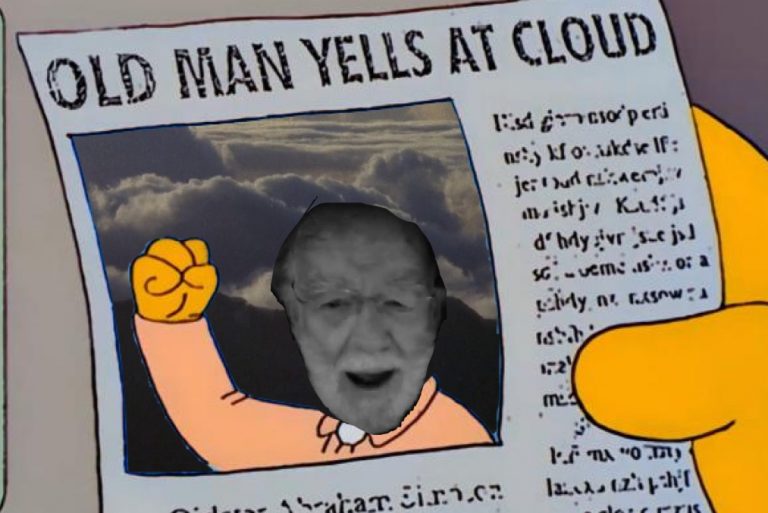

You could spend hours examining all the connections between moments in Koyaanisqatsi – the way the organic shapes of Monument Valley compare with the ugly blocks of project housing, or the grandeur of the wide canyons with the stifling, narrow alleys of the city. Or the visual metaphor of the assembly line, as the juxtaposition of products running down the line with crowds in regimented motion creates an image of a consumer world where people are treated as products.The sequels frequently feel like, as Marge Simpson might say, just a bunch of things that happened. Just look at the montages of famous leaders and international currencies in Naqoyqatsi that have nothing in common except being, well, famous leaders and different kinds of currencies. Or even more hilariously pointless, the montage of tacky 3D renderings of different symbols (a swastika, a star-and-crescent, a friggin’ @ sign) that have nothing in common except being symbols, all symbolizing – well, things that have even less to do with each other. And when the comparisons aren’t meaningless, they’re hilariously blunt, and not just the same thing we’ve heard a million times, but the same thing we’ve heard debunked a million times: one howler in Naqoyastsi flits back and forth between scenes from the Doom games and real-world violence. It’s ironic that a filmmaker who captured such breathtaking skyscapes could become an old man yelling at clouds.

This is true on the macro level too. Koyaanisqatsi develops a few, simple themes from a clear point of view. The same is true of Glass’s score (and he should really be considered co-author on these films), with its throbbing, operatic insistence practically daring you to get bored. His scores for the sequels are too scattershot to demand that kind of attention, with the score in one section sharing no notes or instruments with another. And while it can mostly stand as a musical work on its own, other times it’s just embarrassing. Despite its narrower geographic focus, the score for Koyaanisqatsi is built on the unexpected mix of church organ with Buddhist chanting of a Hopi word. The sequels aim for the same world-fusion mixture, but end up falling back on the same lazy stereotypes as their visual component – some sections sound like they’d be more at home in Disney’s Aladdin. And sometimes they can give the mundane images unearned seriousness (as opposed to Koyaanisqati’s earned seriousness). At one point, the wails of a Muslim prayer played over a rusty car, and I had to ask, are we supposed to be at a funeral for the car?

And Reggio loses his focus just as much as Glass. Everything in Koyaanisqatsi springs from its end-title definition of its title: “1. Life out of balance. 2. Life of moral corruption and turmoil. 3. Crazy life. 4. Life in turmoil. 5. A state of life that calls for another way of living.” You can read that and see how it applies to everything you’ve just seen. In Powaqqatsi and Naqoyqatsi, you have to wait all the way until the end for some hope of context for the disconnected images, and you’ll end up finding none. What does “life as war” have to do with computer-generated tabloid stars and cascades of green zeroes and ones (yes, Godfrey, I saw The Matrix too)?

But despite Reggio’s inability to rebottle the genie, Koyaanisqatsi stands as a towering work of art. I’ll leave you with its final image of awe and horror. A space shuttle ascends into the heavens, with Glass’s gorgeous score making it seem like the most inspiring thing humanity ever achieved. And then, without warning, it explodes. As we watched it ascend, the music ascended – as we watch it descend, the music descends, with that ominous, insistent repetition of the title. The camera zooms in on a piece of shrapnel that for a long time, horribly, appears to be the body of a pilot in his ejector seat. As we get a closer look, it becomes apparent that it’s nothing but a molten chunk of metal. But in this crazy life, is that all humanity’s been reduced to?