After creating about half the Marvel Universe (by a conservative estimate), Jack Kirby, fed up with his lack of creative control, jumped over to their primary competitor, DC Comics, in 1971. They were clearly expecting Kirby to bring the same wealth of imagination that had built Marvel into “the House of Ideas,” and he delivered – an elaborate saga of the “Fourth World” across four series, with incredible new characters and worlds on seemingly every page that other writers and artists continue to draw from. But that still wasn’t enough. Editor Carmine Infantino had Kirby pitch even more new series, and Kirby, expecting to hand them off to other creators, agreed. But then, as a “favor,” Infantino cancelled Kirby’s Fourth World series one by one to free him up to work on these new characters. By 1974, only one, Mister Miracle, remained.

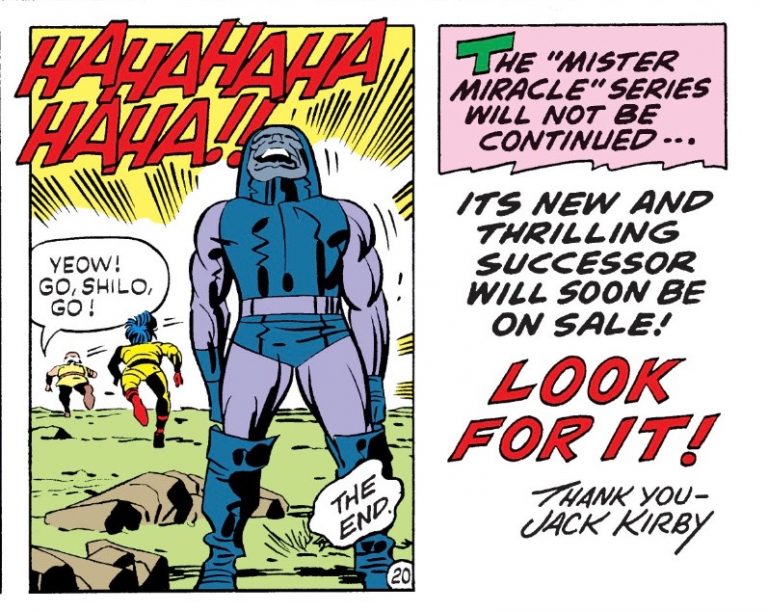

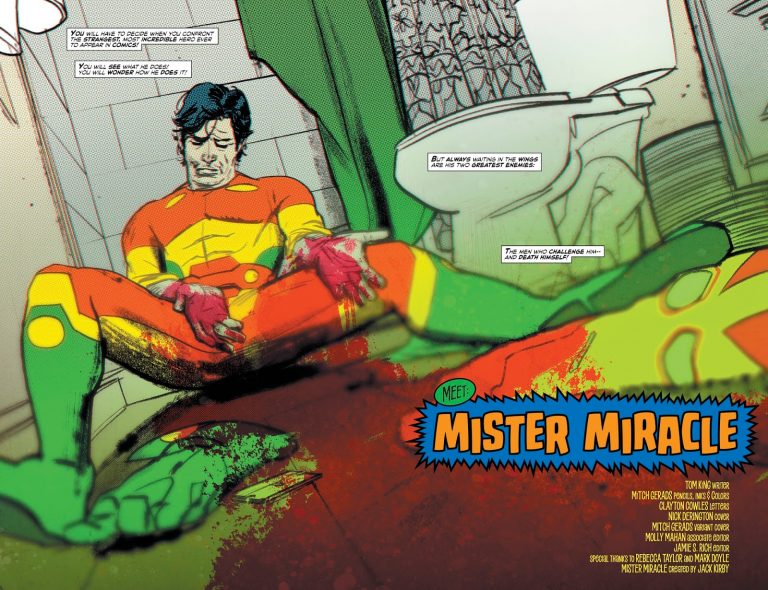

When that, too, ended that March, it was a bit of a mercy killing. After the cancellation of Kirby’s flagship Fourth World series, The New Gods, he almost palpably lost interest in its spinoffs. The rich cosmology of war between the planets New Genesis and Apokolips devolved into run-of-the-mill battles with run-of-the-mill supervillains. That said, he manages to put a bittersweet bow on the whole affair with his final issue of Mister Miracle. It begins like every other issue, with Mister Miracle rehearsing another daring feat for his day job as an escape artist. But this one almost immediately goes south, as the hands of unseen enemies grab his sidekicks Oberon and Shilo. They turn out to belong to the minions of Apokolips’ Virman Vundabar, last seen in those pages years earlier. And he’s soon joined by the rest of Mister Miracle’s colorful enemies: Granny Goodness, Baron Bedlam, and Kanto the Weapons Master. They strap Mister Miracle and his friends into a death trap that even he can’t escape, until the cavalry rides in in the form of the cast of the late New Gods series. Their presence isn’t just a deus ex machina – they’ve arrived because, “Here, in a gathering of our enemies, the Source” – the divine intelligence that guides the New Gods’ Highfather – “has decreed that a wedding must take place!” It’s a deeply personal ending for Kirby, who based the bride, Big Barda, on his own wife Roz. But just like the series itself, the wedding is abruptly interrupted by Kirby’s vision of ultimate evil: Darkseid, “the tiger-force at the core of all things.” He fails to prevent the wedding, but like any good villain, he refuses to admit defeat. “I did spoil it, though –! It had deep sentiment – but little joy. But – life at best is bittersweet!” Kirby’s creative difficulties had obviously embittered this story of good vs. evil: it ends with evil literally having the last laugh. But that bitterness wasn’t enough to overcome Kirby’s natural hypeman instincts:

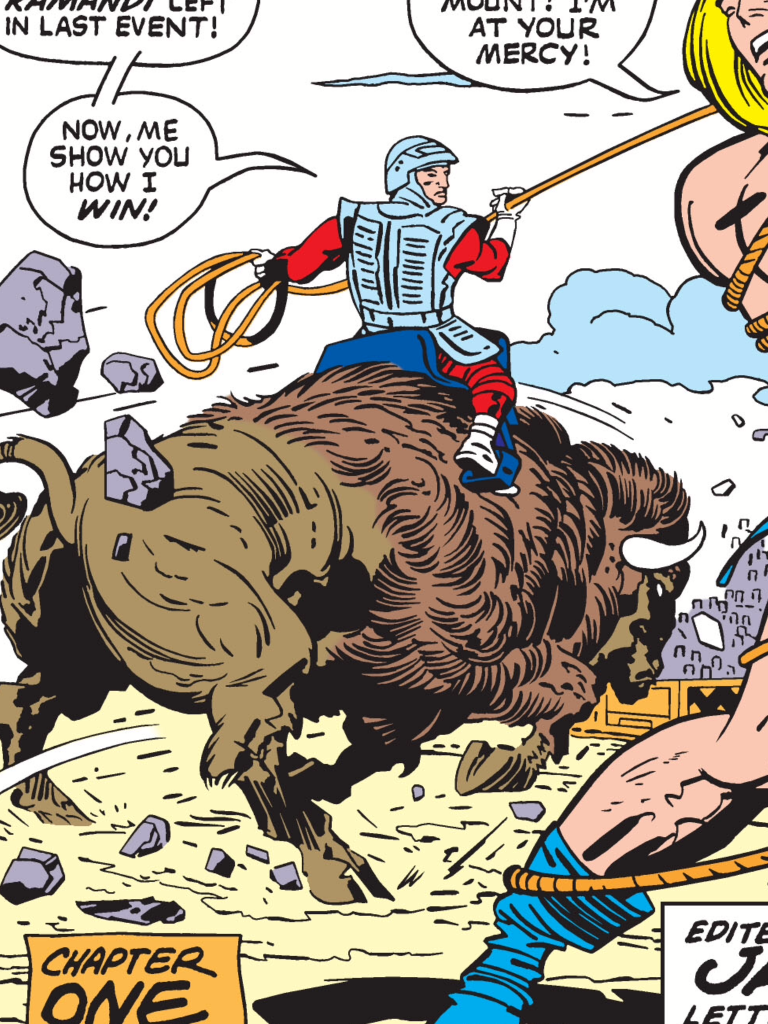

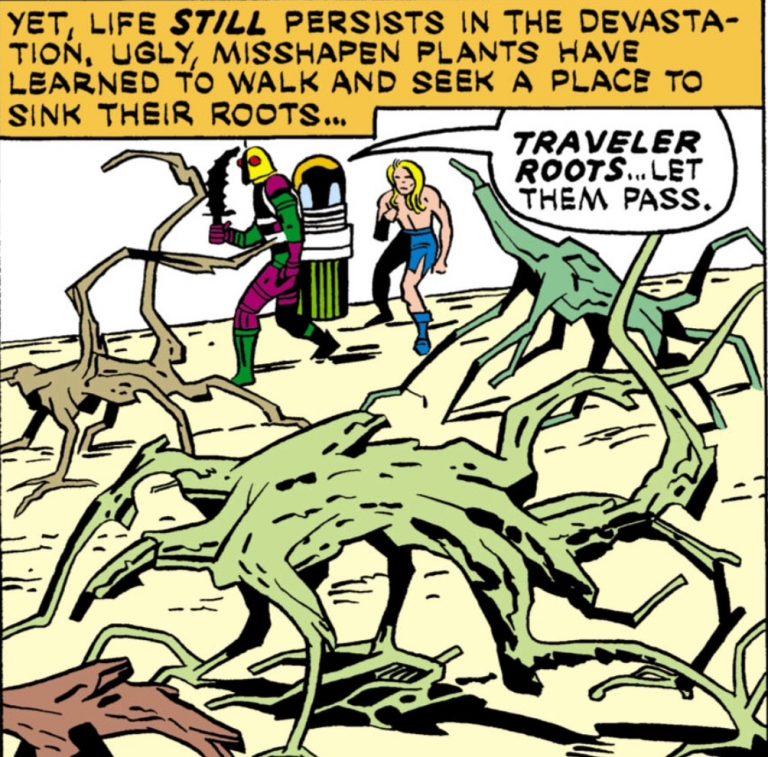

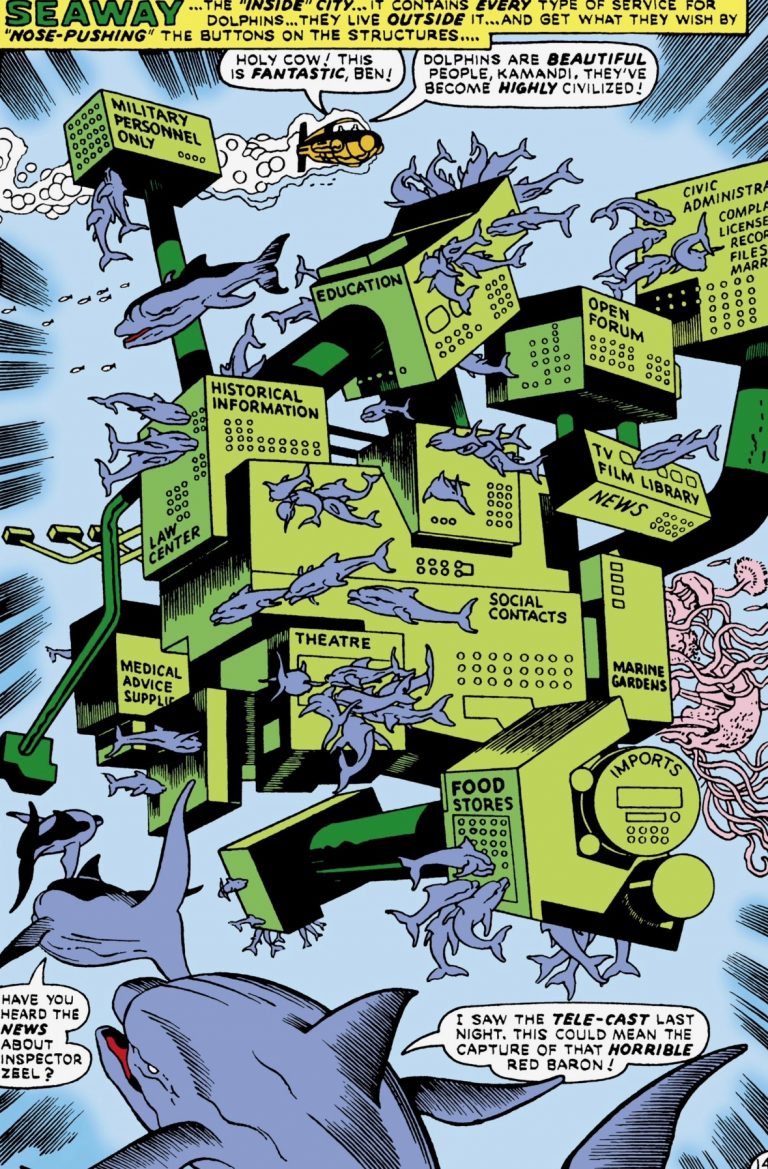

That’s not just hype, either. Creative frustration wasn’t enough to dampen Kirby’s spirit, and if his interest in the Fourth World flagged, he was able to channel it into new characters and new worlds. At first, Kamandi: The Last Boy on Earth doesn’t seem like the product of an original mind. It came about because DC wanted to cash in on the success of Planet of the Apes with a series about a post-apocalyptic world where men had devolved into beasts and horseback-riding beasts had taken the place of men. The cover of the first issue makes its influence clear, with Kamandi rowing past the ruined Statue of Liberty, and inside it even contains a cult worshipping an unexploded nuclear warhead, just like Beneath the Planet of the Apes. But Kirby’s imagination couldn’t be constrained by other creators’ framework. He didn’t stop with apes, populating his future world with a complex network of civilizations of wolves, rat, bats, dolphins, lions, tigers, and bears. Each issue begins with narration over the title, breathlessly promising new wonders in a cadence somewhere between Scheherazade and a carnival barker. It’s a voice something like his old collaborator Stan Lee, but without the self-deprecation or self-aware irony. When Kirby tells you, “DON’T LOOK FOR THE ORDINARY HERE!!” he means it.

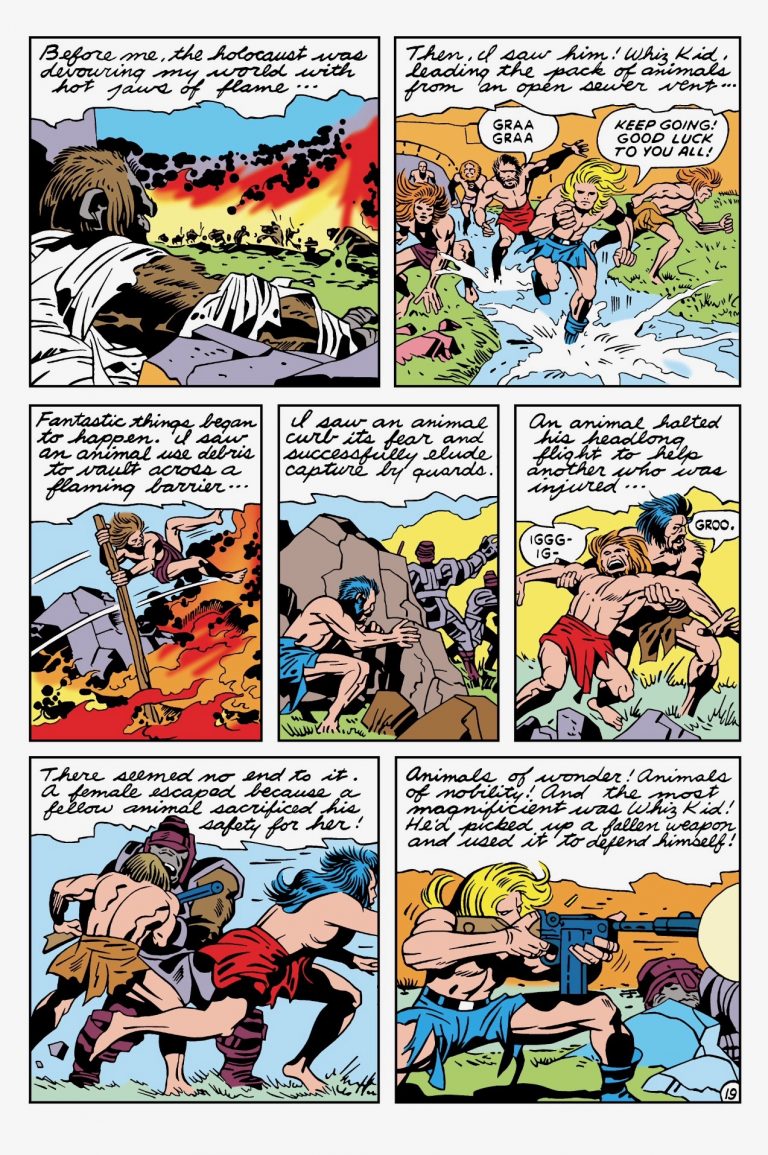

The series’ greatest strength is Kirby’s ability to balance that childlike wonder with a deep and unflinching bleakness. The following generation of comic book writers would pride themselves on how dark and adult their worlds were, but it’s hard to imagine any of them committing as much as Kirby does here. In the very first issue, Kamandi, sheltered until then with the last human survivors in the Command-D Bunker that gave him his name, descends into such complete despair at the state of the outside world that he throws himself on the warhead, hoping to die and take this whole upside-down world with him. He’s pulled back from the brink by the sight of another intelligent human (Ben Boxer, an irradiated mutant, which allows Kamandi to keep his “last boy” title). But he’s not entirely wrong either. Earth After Disaster is full of wonders, but it’s also a cruel and uncaring place. Kamandi walks it alone, and any companion he finds could be murdered the next moment.

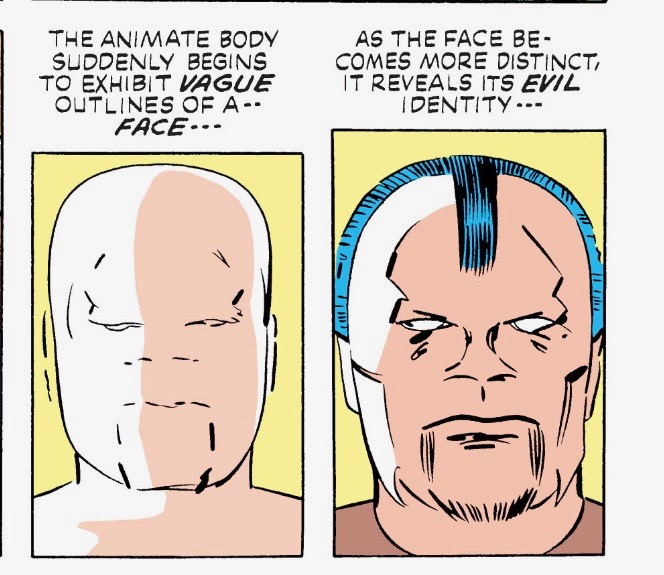

Jack Kirby made his name as the creator of Captain America, and Kamandi, like him, is a man out of time. And not just in the sense that he’s been raised in the last remnants of pre-Disaster earth before being forced into the future. For all of his talk of restoring human civilization, Kamandi is also a character of raw, primal violence, one of World War II veteran Kirby’s many reckonings with the role of the warrior in peacetime. Kirby’s heroes aren’t the clean-cut do-gooder fantasies of most comics. He had seen what violence really looked like, and that was what he drew, most memorably in a New Gods story where the heroic Orion’s brutal torture of a villain literally revealed his true, ugly face. Kamandi is just as savage, sometimes frighteningly so, a kind of bizarro version of Mowgli or Tarzan: a wild human raised by human fitting uneasily into the civilized world of animals.

Unlike most of his generation, Jack Kirby had a deep sympathy for the concerns of the youth that defined the sixties and seventies. It’s easy to see the connection between the long-haired Kamandi’s rage at a world that condescends to him as a subhuman pet and the youth movements of the time. In fact, his primal rage and violence seems to anticipate the shift of the next few years, as “punk” replaced the pacifistic “hippie” as the dominant subculture. But for all Kirby’s bombast, the most powerful moments of pain are also the subtlest, like Kamandi silently walking away, head bowed, from a preserved Chicago he had believed sheltered his own kind. It turned out to be nothing but a Westworld-style theme park, and Kirby enhances the haunted mood with a long-dead announcer’s voice echoing over the intercom.

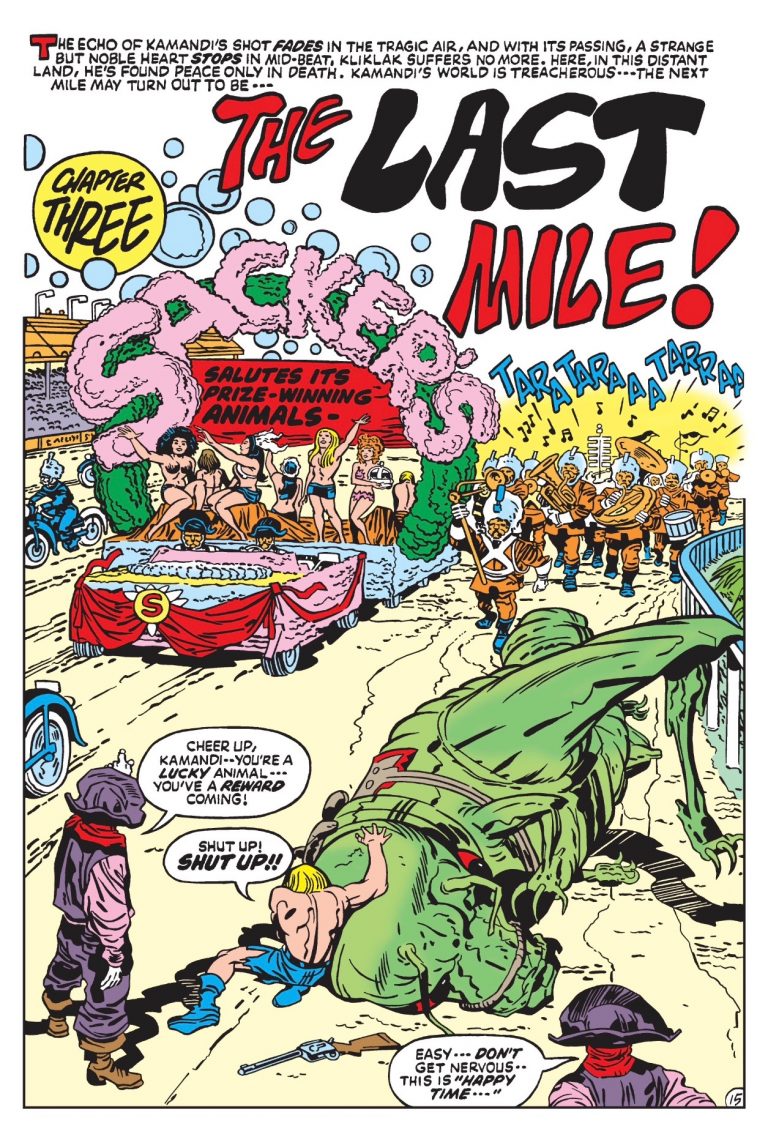

Or the death of Kamandi’s pet Kliklak, where his private pain is overwhelmed by the public celebration in his honor.

Most powerful of all is the quiet, fatalistic melancholy of “The Hospital.” In the aftermath of the previous issue’s wonderfully bizarre story of a cargo-cult of apes who recreate the Watergate trials in a ritual complete with “death subpoenas,” Kamandi wanders into a hospital where the gorilla Dr. Hanuman is experimenting with a drug called “cortexin.” Working from the notes of Michael Grant, a human scientist working in the midst of the Great Disaster, Hanuman realizes the formula might be the origin of his own civilization, and of the whole world of animal-people he lives in. History continues to repeat itself: an army of tigers attacks the hospital, and Hanuman insists on continuing his work just as his predecessor had. Dr. Grant’s notes narrate the story, and his narrative of events from generations earlier double as a description of the present.

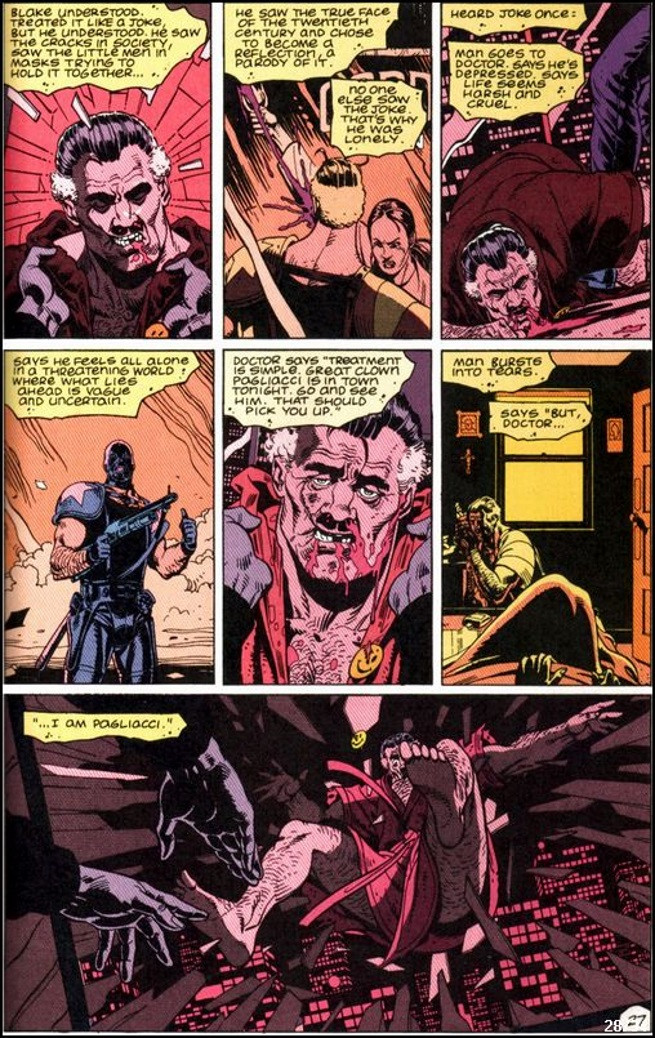

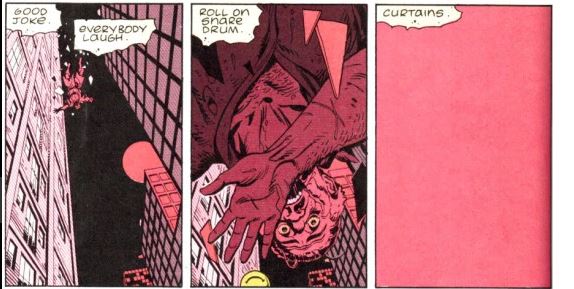

Kirby experiments with the tools of the medium, using narration boxes as a counterpoint to the story instead of simply describing it. It’s a trick future writers would pick up on, from Alan Moore’s iconic juxtaposition of the old joke about the doctor and Pagliacci with the death of another Comedian

Kirby experiments with the tools of the medium, using narration boxes as a counterpoint to the story instead of simply describing it. It’s a trick future writers would pick up on, from Alan Moore’s iconic juxtaposition of the old joke about the doctor and Pagliacci with the death of another Comedian

to Tom King’s use of Kirby’s own hyperbolic narration of the original Mister Miracle and the ominous statement “Darkseid is” as a counterpoint to the depressing mundanity of his present life.

Unfortunately, “The Hospital” also marks a less exciting turning point for Kamandi. It’s the last issue inked by Mike Royer and the first inked (partially) by D. Bruce Berry. Looking at the two artists’ work side by side is like one of those “Wi fi drops by one bar” memes. Kirby has named Royer as his favorite inker, and it’s easy to see why. Royer faithfully followed Kirby’s detailed and beautifully shaded pencils. His flexible line (apparently created using a paintbrush) filled Kirby’s figures with grace and life.

Berry’s thin, uniform line sucked that life right back out; and as for grace, his figures are so clumsy they seem to have been drawn left-handed. Compare the dull, jagged circuits Kirby/Berry draw behind a Chicago Land robot’s face…

With the way Royer faithfully renders the gorgeous technological abstractions that have become Kirby’s trademark.

Figures anywhere more than a couple inches from the reader’s face suffer the most under Berry’s pen. Frequently, he’ll neglect to draw their pupils, making them look like Evil Dead zombies.

Other times, he’ll draw an iris in only one eye, making them look more than a little insane…

Or give them catlike slits.

And most times he’ll awkwardly scrawl over Kirby’s characters like a child with a crayon to create doodle-like figures like these:

Most of Kirby&Berry’s figures look like Kirby&Royer’s depiction of Baron Bedlam’s half-formed face in Mister Miracle.

But these handicaps weren’t enough to dampen Kirby’s imagination. His Berry collaboration see him expanding his boundless post-apocalyptic world even further, as Kamandi and the dolphin Inspector Zeel journey into the irradiated Dominion of Devils.

When Kamandi and Zeel return to the dolphins’ city, it provides another full-page showcase for Kirby’s imagination.

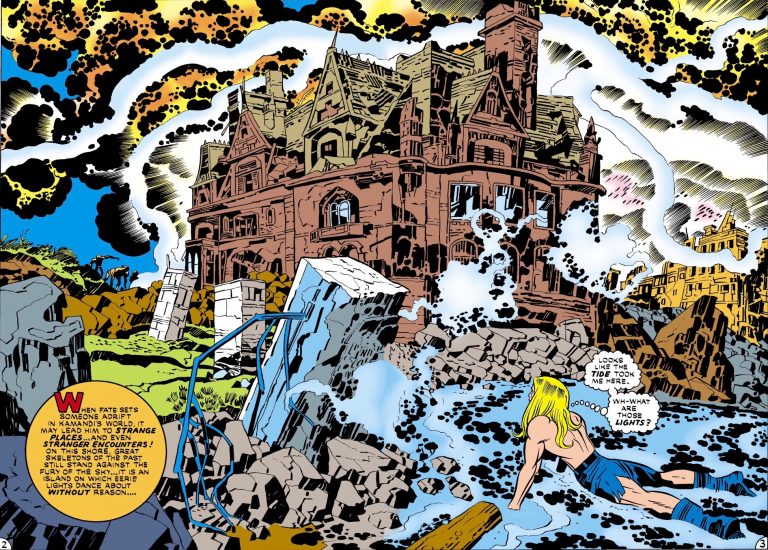

“The Exorcism” is another highlight, as Kirby reshapes The Exorcist as thoroughly as he had Planet of the Apes or Westworld. You haven’t really seen a haunted house until you’ve seen a Kirby haunted house, crumbling and crackling with cosmic energy.

Kirby’s longtime assistant Mark Evanier said, “He was a man who told dynamic stories about dynamic people, and drew from a powerful, almost life-affirming point of view. Someone at the time made a comment – I forget who – that The Demon [another Kirby series] was a comic book about death, made from the perspective of someone who believed in fighting for every last scrap of life. This was in contrast, the forgotten commenter commented, to other ghost and monster comics”– and movies like The Exorcist – “that treated death as inescapable and overpowering – ‘death from the perspective of death.’” These comments apply just as well to “The Exorcism.” That dynamism is the flipside of Kamandi’s violent savagery. While the other characters are paralyzed with terror, he continues moving and acting, finally discovering the source of the horror and intimidating it into submission. And if The Exorcist portrays demonic possession causing outer change, Kirby uses his boundless vision to push that into the realm of full-on body horror.

Unfortunately, Berry manages to sabotage that too.

Kirby even predicted the Dreamworks Animation formula decades early. What a visionary!

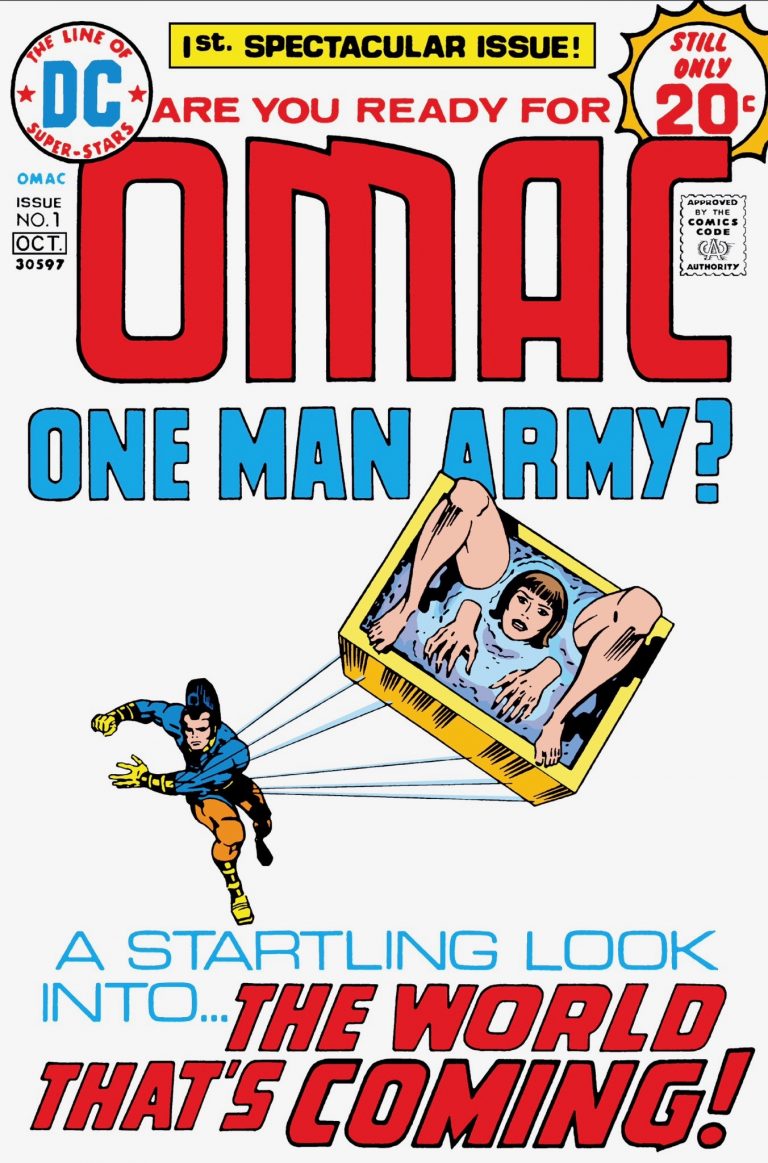

Kirby found another, possibly even more boundless outlet for his imagination in another possible future for OMAC. Kirby was deeply influenced by his Jewish faith, which teaches of HaOlam HaBa, the World to Come; or, in the Zohar, “the world that is coming, constantly coming, never ceasing.”

If you’re familiar with the series, you know where this is going.

That cover shows that Kirby’s other possible future is going to even stranger places with its hallucinatory image of a box containing a scrambled woman’s body, head between the legs, suggesting contortion, birth, or some bizarre form of fetish art. It’s made all the more shocking by the uncharacteristic minimalism: a plain white background, with no other figures except a tiny OMAC in the background, tossing this horror right in the reader’s face.

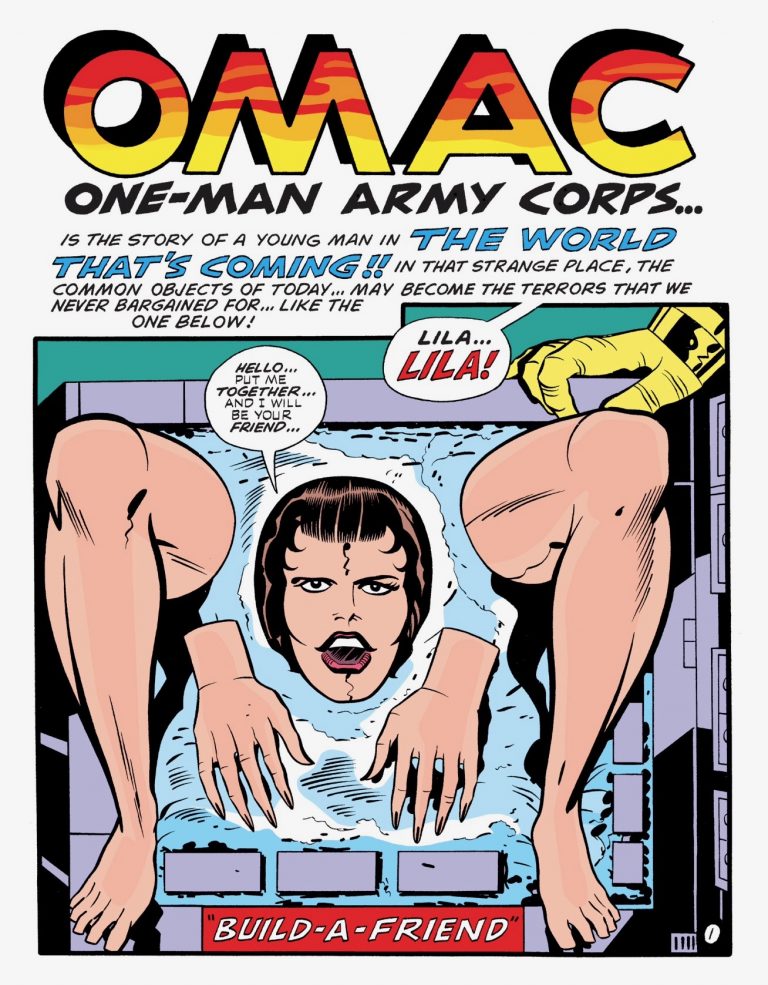

The book’s contents are no less feverish. We open on an even more in-your-face view of the horrible “Build-a-Friend.” Like the rest of the series, it opens with Kirby in full hype mode, describing the World That’s Coming in the same breathless tones as Earth After Disaster: “OMAC: One-Man Army Corps…is the story of a young man in the world that’s coming!! In that strange place, the common objects of today…may become the terrors we have never bargained for…like the one below!” (Later writers would establish that OMAC takes place sometime between our time and Kamandi’s, and that the two characters were family in a more literal way than they already were).

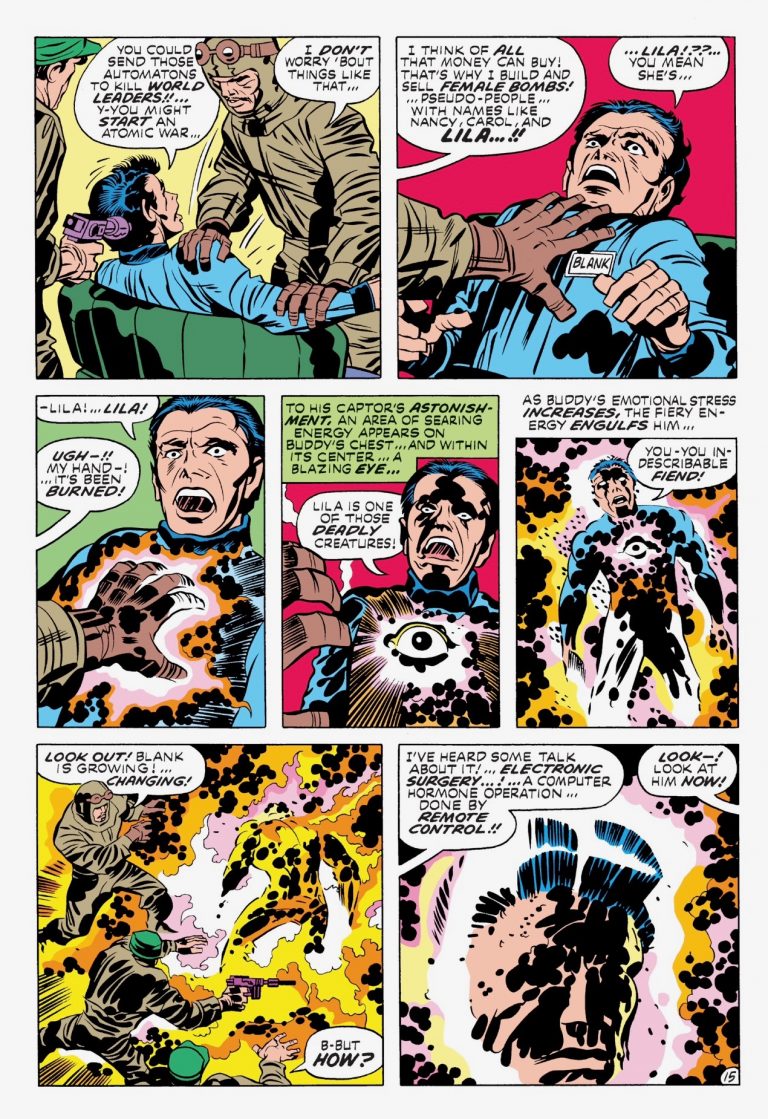

From there, the scene explodes into an all-out brawl, before literally exploding as OMAC destroys the Build-a-Friend factory. He walks out indomitable, before bowing it in despair like Kamandi leaving the ruins of Chicago. We find out why in a flashback: Lila, the disassembled Build-a-Friend he sadly said goodbye to before detonating the factory, had been his only friend. Before his transformation, he had been Buddy Blank, a scrawny sad-sack mercilessly bullied by his coworkers at Pseudo-People Inc. Even his boss blames him rather than taking action: “Someone’s always lying when you’re involved, Blank! You’ve got a ‘persecution’ complex!” He finds a sympathetic ear in Lila, but doesn’t realize she’s just another cruel prank: the lab techs are using Buddy as a guinea pig in a kind of hands-on Turing Test. When Buddy learns the truth, his mental breakdown is accompanied by a physical breakdown as horrifically visceral as only Kirby could make it:

Yes, as that classic bit of Kirby gobbledygook says, “a computer hormone operation…done by remote control!!” courtesy of an eyeball-shaped satellite called Brother Eye, has turned him into a one-man army corps. Kirby has amped up the persecution-revenge subtext of so many superhero revenge stories into the text. The association of these fantasies with recent outbreaks of real-world violence has made this story more uncomfortable. But despite Kirby’s love of violent, aggressive antiheroes, Buddy Blank is lacking that kind of toxicity, even as his future dystopia encourages it. When his boss sends him to “psychology section,” he turns down an opportunity to cut loose in the “Destruct Room” by kicking one of the company’s “Pseudo-People” in the pants: “No, thanks. The company makes ‘em too ‘lifelike’ for my tastes…Bah! I don’t feel like burning cars either…I’m not angry at anybody…I just feel depressed, that’s all.” He only develops violent instincts when he can channel them for the cause of justice. Or is that just a fig leaf? Don’t all these angry young men believe their targets deserve what they get?

Despite the quality of his work for DC, Kirby was still unhappy. He had come there in the hopes of receiving a bigger share of the fruits of his labor; but as we saw with the cancellation of the Fourth World series, he was still plagued by editorial interference. All the shuffling around as DC scrambled to find the next big hit exhausted him: he compared the move to “Escaping a slave ship onto the Titanic.” When DC started assigning him scripts from other writers on Kamandi and other series two years later, he decided he’d had enough and went back to Marvel. Even though he’d introduced several new series in the interim, Kamandi and OMAC were the only ones to survive until his departure, and Kamandi was the only one to continue without him. He continued to write his own scripts at Marvel, which fortunately didn’t reopen his fraught partnership with Stan Lee. And his imagination continued unabated, as he created new characters like Devil Dinosaur, the Celestials, and the Eternals, who are coming soon, as they say, to a theater near you. That upcoming film, and DC/Warners’ attempt to beat it to market with a New Gods adaptation, is a testament to Kirby’s legacy. He may not have been recognized in his lifetime, but he’s sure to be remembered far beyond it.