Since Cinemascore began operation in 1979 only 19 films have received the lowest score. In this series I’ll be reviewing those 19 films. This week, we all do what we can to ensure a good harvest.

So What is it?

The original Wicker Man is one of those movies that lives in the strange alchemy between lots of things that shouldn’t rightly work. It’s a horror story with a lot of musical numbers. It’s a surprisingly authentic portrait of a small eccentric community but is also permeated with an odd unreality. Everything is heightened, almost surreal, and at the same time feels commonplace and down to earth; with the school rooms, and playgrounds, and bustling bars, and polite shop owners giving it a stronger sense of place than any other horror film I’ve ever seen.

What The Wicker Man really thrives on though, is the odd tension it creates in the audience – between the desire to identify with the detective (a stranger to Summerisle just like us) looking for a missing girl, but then finding the islanders, with their bawdy songs, and naked dancing, and consistently cheerful dispositions, to be a lot more appealing than this stick-in-the-mud asshole cop. When the turn comes, we find the cop is of sturdier and deeper faith than we gave him credit for and the Pagans are just as casual around ritual murder as they are around sex and nudity. It cuts very deep and is disorienting and haunting in a way few other movies have ever managed. The Wicker Man is a miracle, one of those magic movies where all the elements came together in precisely the way necessary to make it work, and only a fool would think they could reconjure that magic. And there’s no greater fool in Hollywood than Nicholas Cage.

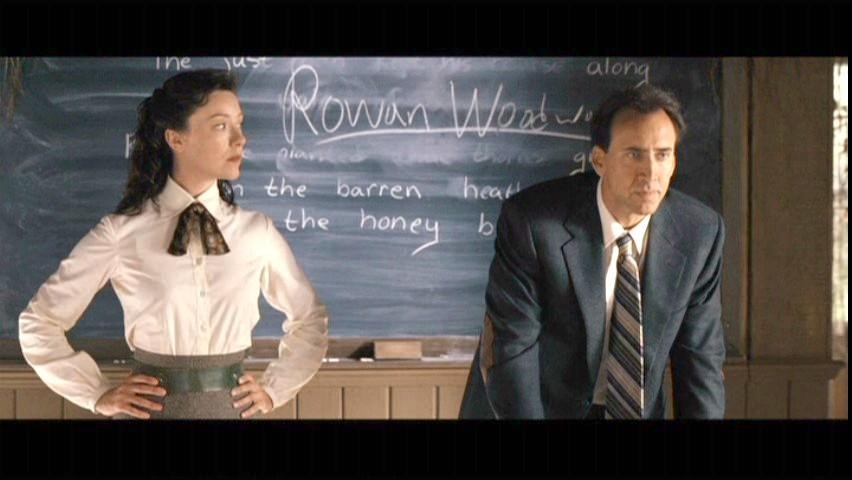

Right off the bat, the remake makes the somewhat admirable but ultimately misguided decision to reverse the central dynamic and drains the movie of all its tension along the way. Instead of a conservative cop investigating a hippie-dippy commune, we have a worldly cop investigating a conservative quasi-Amish town. The new islanders are matriarchal, which is an interesting wrinkle, but unfortunately this is the nightmare feminism of many a recently divorced Hollywood screenwriter, with stern sexless women whose only use for men is lifting heavy logs and carrying ominous child-sized burlap sacks, and whose only pleasure in the world is to stand about in heavy clothes and glare disapprovingly at Nicholas Cage. There’s no sense of a functioning community here, and certainly not one that anyone, man or woman, Christian or Pagan, would have any desire to join.

The plot itself is both far more convoluted and much thinner. The original narrative is driven by a core mystery; our protagonist is a police inspector who has been sent an anonymous letter and photo of a missing girl, but when he arrives on Summerisle to investigate, everyone, including the girl’s own mother and baby sister, insist that she never existed. It’s a good hook, and it forces the detective to explore the island and engage with the culture in order to unravel the mystery.

Cage, on the other hand, is not a police detective, but an out of state motorcycle cop haunted by a car accident he saw once and we will see many, many times, that killed a woman and her daughter, who is contacted by his ex-fiancé to help investigate her missing daughter who he will later discover is his own daughter (though the story is much clumsier for leaving him in the dark about this detail for so long, and then makes no use of the knowledge once he gets it). This takes far longer to set up (the scene that opens the original doesn’t show up until we’ve gone through 15 minutes of laborious set up in the remake) and yet once we’ve finally reached the island, there’s far less to actually do.

This is because there’s not really a mystery here. Cage is informed immediately that there is a sinister conspiracy at play, he has a confidant that ought to be able to tell him what he needs to know about the inner workings of the cult, and he has a vocal witness who he can take to the police and get a full-fledged search going – were he so inclined. Without any, you know, plot, to guide him, Cage is left flailing around the movie with a constantly escalating frustration that feels more than a little like a meta commentary on the film’s own ineptitude, spending most of his time screaming at an increasingly bewildered series of women, until it’s finally time to get turned over to the bees.

So Why the F?

There are three distinct periods in Nicholas Cage’s career. First, he was Coppola’s nephew, a talented up and coming actor who would take risky roles and totally give himself over to bold auteurs like the Coen Brothers or David Lynch. Then, somewhere around the time he won his Oscar for Leaving Las Vegas, he became Nicholas Cage: Movie Star, able to balance work in ridiculous but well made blockbusters like Face/Off (B+) and Con Air (B+) with more respectable fare like Bringing Out The Dead (C-) and Adaptation (C).

The third period of Cage’s career didn’t begin with The Wicker Man (F), but shortly after, when edited together compilations of his performance in the film started to hit YouTube (which had only just launched the year before). The YouTube supercut is really the ideal medium for an actor who relies so heavily on manic outbursts, and Nick Cage quickly became Hollywood’s preeminent madman, a reputation that only increased as the IRS chased him through an ever denser series of low budget actioners and high concept indies. 2006 was the last time audiences could sit down to watch a new Nicholas Cage movie and reasonably be disappointed when it turned out to be an outlandish fiasco centered on the bizarre adventures of an absolute lunatic.

So Were they right?

In its own way the modern Wicker Man has become just as much of a cult classic as its predecessor. This was a difficult movie to write about because of just how much its biggest and strangest moments have been absorbed by the culture:

- “HOW DID IT GET BURNED?! HOW DID IT GET BURNED?!”

- “NOT THE BEES! NOT THE BEEEEEES!”

- The bear suit.

- The many solid character actresses that Nicolas Cage punches in the face or judo kicks across a room.

It’s all so familiar now, such a fundamental aspect of who Nick Cage is as a star and an icon. I have to admit that the familiarity has dulled the comedy from when I first saw this movie [Jesus Christ] over a decade ago. But even watching it alone with my little notepad, knowing all the gags before they came, waiting for jokes that aren’t even in this cut, I still found it solidly amusing. (What hit me hardest this time, was the end credits dedication declaring the movie “For Johnny Ramon”. A low blow to a man who couldn’t even defend himself, and only a hair different than ending with “The Aristocrats”).

For all its memeification, for all the tired and worn out impressions, for all the blunting and wastefulness of one of Hollywood’s strangest and bravest talents that has defined the last decade of Nick Cage’s career, this is still an absolutely essential film to anyone who’s ever enjoyed sitting back with a group of friends and having a laugh at a movie’s expense. This is one of the all-time Great Turkeys. It deserves at least a Beeeeeeee–

Next Time: We turn the column over to guest writer, The Ploughman, to find out whether 2008’s Disaster Movie really lives up to its title.

[Editor’s Note: Whoa, whoa. A movie whose only audience is the lowest common denominator that was given an F by the lowest common denominator? You kicked this beehive, you wear the ceremonial bee funnel.]