This segment of The Solute looks at 5 movies that came out this month in previous years by factors of fives. Today, we look at April 2000.

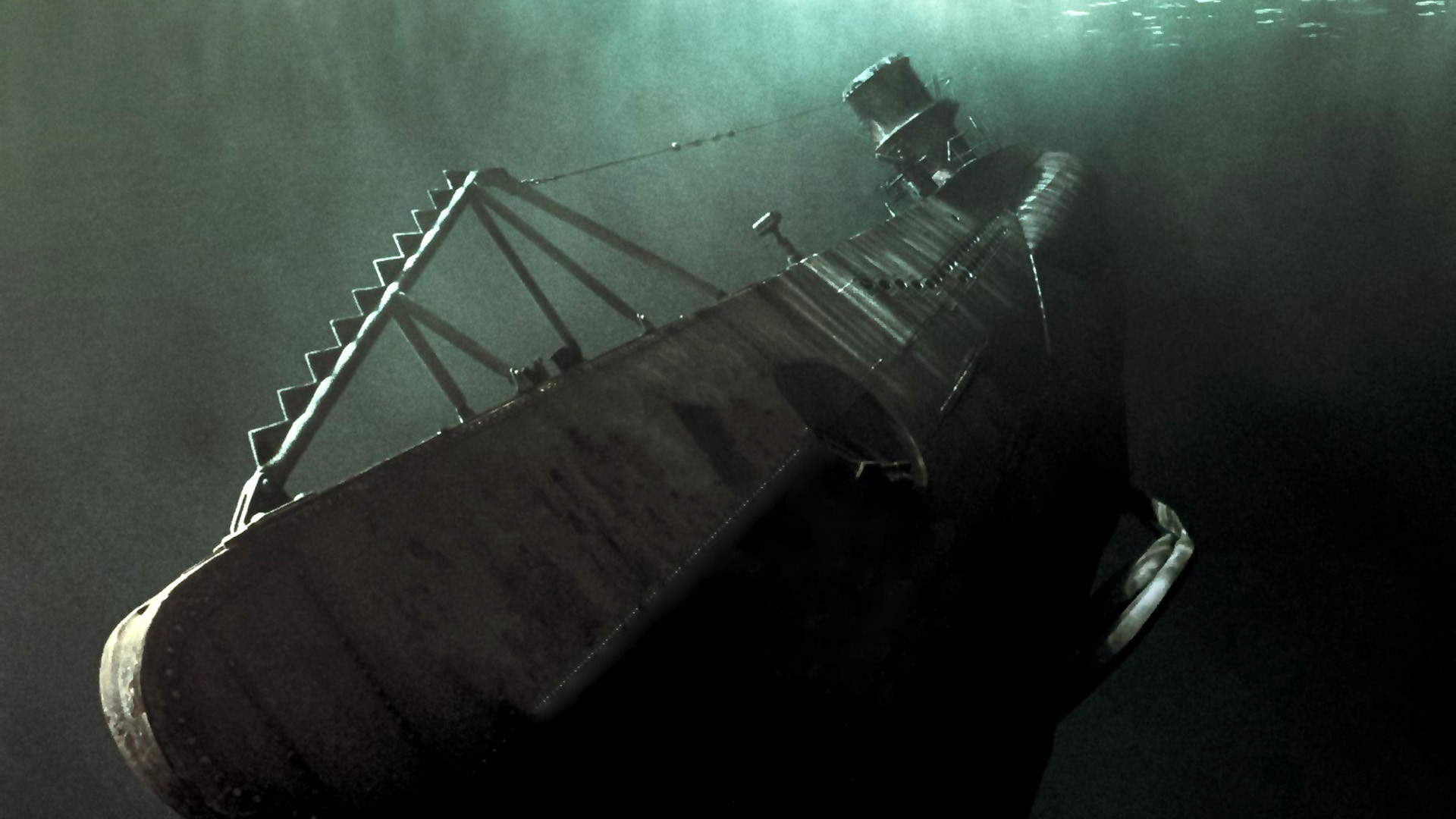

Top of the Box Office: U-571

U-571 is one of the most unexplained movies I have ever seen. U-571 was an actual German submarine in World War II that was bombed off the coast of Ireland in 1944 by the British. U-571 reimagines the sub as a central role in the Allied retrieval of the Enigma coding machine. It also reimagines America as having a central role in the retrieval of the Enigma coding machine, even though America HADN’T EVEN ENTERED THE WAR when the real Enigma had been picked up.

In order to explain the full depth of the strangeness of U-571, I have to go through the cast and place them in terms of their career. U-571 was led by Matthew McConaughey well before the McConnaissance. At this point, his biggest roles had been Ed in the relative flop EdTV, and the preacher/slight love interest in Contact. The biggest star in U-571 was Harvey Keitel, who, at that point, was still known for his harder-edged foul-mouthed roles from Tarantino and Ferrara. Also in the mix was Bill Paxton, whom we all know can curse a blue streak, and Jon Bon Jovi(?). Yet, U-571 was a war movie that retained a PG-13 rating. So, Keitel’s usual poetic tapestry of swear words were kept out of a high pressure movie where it would have been natural for him to swear.

Somehow, this historically inaccurate, non-violent, war movie with neutered language got decent reviews in America leading to financial success before being derided by Tony Blair as an affront to British sailors. When I saw the pre-screening, I didn’t get tension or thrills from the movie because I kept waiting to be eased into the soothing swears of Harvey Keitel, but they never came. It won an academy award for sound editing and serves as a test disc for sub woofers everywhere.

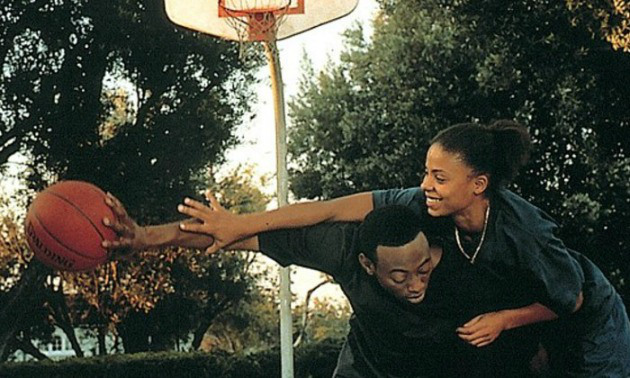

Endearing Romance: Love & Basketball

Cultural Critique: American Psycho

Bret Easton Ellis’ ultra-violent blackly comic novel American Psycho is about Patrick Bateman, a closet case loser who fantasizes he’s the life of the party. Every time he’s humiliated, Bateman turns to violently misogynist fantasies to preserve his own ego. However, the novel is written from a first person perspective without many signals separating the fantasies from reality, thus leading to the charge that the novel is actually about a typical 1980’s Wall Street he-man who harbors and encourages a seething hatred of all women. The film version, adapted by Guinevere Turner and Mary Harron, reimagines the story with a feminist perspective, marking him as a typical he-man misogynist but also ridiculing him as a closet case loser…inadvertently stumbling onto the point of the novel. The final product is a blackly comic horror movie that is as patently ridiculous as it is frightening, toning down the violence but still capturing the flavor.

Auteur Beginnings: The Virgin Suicides

Sofia Coppola, daughter of Hollywood giant Francis Ford Coppola, made her mark on Hollywood with a melancholic period piece set in 1974 Grosse Point, MI. The Virgin Suicides tells the story of five sisters growing up in an overprotective upper class household, documenting their struggles with rebellion and freedom through the eyes of the boys in the neighborhood. The boys watch the girls grow into women without knowing the inner struggles of the girls who are endlessly trying to break free of their gilded cage. This was a solid first feature, displaying a mastery of tone and image, that set Sofia up as the rightful heir to the Coppola cinematic throne.

Experimental Essential: Time Code

Mike Figgis tried to work within the Hollywood system, but they didn’t get along. In 1995, his petulant Leaving Las Vegas, about an alcoholic and a prostitute, earned Nicholas Cage an Oscar and both Figgis and Shue were nominated for Best Director and Actress respectively. But, in the 5 years after, he made increasingly eccentric low-budget flops showing his restlessness with the form. Time Code is his boredom with the single screen story made into a movie. Told simultaneously with four cameras and no edits, Time Code allows the audience to follow four interrelated stories at once. The cameras interconnect, sometimes changing characters and plots. The experiment predates the modern era of multiple devices fighting for attention, engaging the viewer by allowing them to soothe their ADD tendencies by allowing them to visually edit between the four separate screens. In the theatrical version, Figgis highlights what he thinks is most important through sound editing, but the DVD allows the viewer to even control that through the remote control. The stories themselves are rather shallow jabs at Hollywood and its shallowness, but the form is more important than the plot and other deeper meaning. It’s a fun zesty exercise, just don’t expect to bring much back to chew on.