If Phantom of the Rue Morgue struggled to make the classic monsters of the thirties relevant to a fifties audience, Creature from the Black Lagoon did a far better job bridging the two eras. The monsters were no longer supernatural, but explained by (usually very flimsy) science, still waiting to be discovered in the depths of space or unexplored corners of the earth. The Creature from the Black Lagoon is about one of these sci-fi monsters, but it still has an eerie, supernatural quality. Of course, it had the advantage of coming from Universal, the studio that created the best of Old Hollywood horror, and the association with the Universal Monsters family of Dracula, Frankenstein, and the rest, has done a lot to keep Creature in the collective memory.

But it more than stands on its own merits. As he would prove with The Incredible Shrinking Man a few years later, director Jack Arnold knew how to find poetry in camp. That film ended with its hero expanding his strange affliction from kitsch to metaphysics: “So close — the infinitesimal and the infinite. But suddenly, I knew they were really the two ends of the same concept. The unbelievably small and the unbelievably vast eventually meet — like the closing of a gigantic circle. I looked up, as if somehow I would grasp the heavens.” Creature from the Black Lagoon opens in the heavens, in a sequence that would seem more at home in The Tree of Life or at least Fantasia. We begin at the very beginning, the birth of the universe in cosmic destruction. From there, we move billions of years to the present, a shimmering beach in radiant black-and-white photography.

There will be other images like these, equal to any of the shadowy grandeur of Arnold’s Universal forebears, or even their other students like Jean Cocteau and Georges Franju who backgrounded the thrills to focus on the artistry. Images like Julie Adams stretched out on a rock in the Creature’s cave in shining white, surrounded by mists. Images like the groundbreaking underwater sequences, where the characters move with eerie, weightless grace, the Creature gliding beneath Adams’ character (actually played by a double, professional swimmer Ginger Stanley) like her shadow-self.

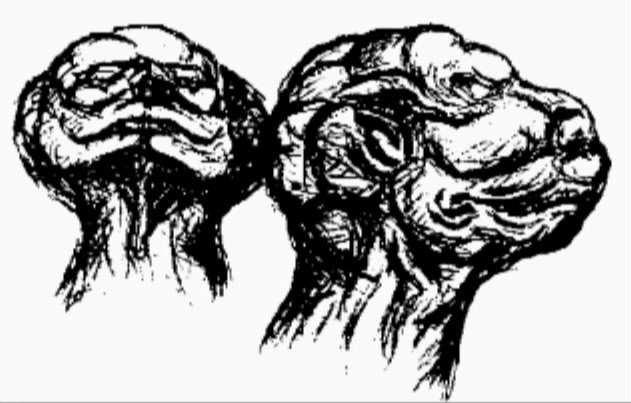

Most of the rubber-suit monsters of the Creature’s generation were weighted-down and clumsy under all those prosthetics. Even Godzilla lumbers around gracelessly, though the filmmakers were able to use that to their advantage. Godzilla destroys his surroundings every time he moves; the Creature glides through them. Instead of being burdened by his costume, stuntman Ricou Browning, another professional swimmer, wears it so lightly you can almost believe that really is his skin. Some of that credit goes to the design by Disney animator Millicent Patrick. Even after sixty years of advances in special-effects technology, it’s as convincing as ever: the only real “tell” is the thin, floppy gloves that represent his flippers. I’d even say it looks better than most higher-tech monsters. And if you don’t believe me, look no further than the Creature’s return in the post-Star Wars golden age of effects films, recreated by one of that era’s greatest technicians, Stan Winston, for The Monster Squad. The new technology allowed for more detailed textures in the Creature’s scales, but they still look more obviously plastic and inorganic than Patrick’s design. The old Creature’s breathing was eerily lifelike, looking just like a real fish gasping for air. But the new Creature’s gills and jaw hang limply and his stomach creases when he bends over, clearly just prosthetics and not part of a real body.

Creature from the Black Lagoon is full of moments of transcendence, even if they do have to struggle to rise above the swamp of monster-movie clichés and silliness. The characters flatly intone the same kind of pseudoscientific technobabble nonsense as any other film it might have shared a bill with. The chilling shots of the Creature’s webbed claw entering the frame are undercut by the hilariously hysterical scores that blasts over it every time. But at its best, Creature has the timeless, lizard-brain power of dreams and myths.

Them! and Godzilla, on the other hand, are both heavily grounded in the timely fears of the Atomic Age. It’s no secret that Godzilla, the primeval creature awakened and possibly mutated by atomic bomb tests to destroy Tokyo, was a blunt metaphor for the horrors of Hiroshima. At one point in the process, director Ishiro Honda even considered giving him a mushroom-cloud-shaped head.

And of course, Them! and the other irradiated critters of American monster movies reflected that country’s atomic anxiety. But looking at these movies together shows that the two nations’ fears were very different. In American films, the radioactive monsters can reflect real-world fears of nuclear annihilation, but they can also be a lazy justification for the monsters’ existence. This bit of dialogue from Monster from the Ocean Floor is revealing:

“What could cause it to, uh, grow out of proportion this way?”

“It could be one of many things. Some freak accident… dietary supplement…it even could be caused by the radiation from the Bikini explosion.”

In other words, it doesn’t matter as long as we get to the fun part — it might as well as be a dietary supplement, however that’s supposed to work. To Honda, it matters a lot, and there’s not much fun to be had; it’s almost cliché by now to point out how relentlessly grim the original Godzilla is, and how far the traumatically realistic recreation of life and death in the face of nuclear annihilation is from the family-friendly action franchise it became. But it’s probably worth pointing out that incarnation of Godzilla didn’t catch on until the first generation born after Hiroshima came of age. The generation that lived through it might not have been able to stomach movies that treated the incarnation of the Bomb so lightly. In America, the creator of the bomb but itself safely un-nuked, audiences didn’t have the same qualms. Edmund Gwenn (the star of Miracle on 34th Street, cheerfully slumming) warns the assembled military in Them! “Man, as the dominant species of life on earth, will probably be extinct within… a year?” But he doesn’t say it with the conviction of Godzilla’s cast. Godzilla exploits the helpless terror of the victims of nuclear war. Them! exploits the fears of the victor: the guilt and responsibility that come from a nation that has unleashed this existential threat on the world. At the end, the surviving hero asks, “If these monsters got started as a result of the first atomic bomb in 1945, what about all the others that have been exploded since then?” Edmund Gwenn, answers, with more conviction this time, “Nobody knows, Robert. When Man entered the atomic age, he opened a door into a new world. What we’ll eventually find in that new world, nobody can predict.”

Them! can’t stand next to Godzilla for sheer terror any more than it could for social commentary. What can? But it’s still surprisingly effective. Especially in its first half, it relies more on atmosphere and dread than spectacle and jump scares. The deserts of New Mexico look misty and haunted in black and white, and the sandstorms obscure everything in a dreamlike haze and create eerie, whistling wind. But not even that’s as eerie as the ants’ calls. Somewhere between a cicada’s buzzing and a nocturnal bird call, it’s a haunting sound that’s far more effective than the stock clattering of future big-bug movies. Godzilla also features a sound effect that’s far more unsettling than its successors’. The big guy’s roar has become instantly recognizable, written by his fans as the onomatopoeia “SKREEONK!” But that’s not what we hear in the original. It’s a deeper, more metallic tone (less “SKREE,” more “ONK”) that doesn’t sound like it should come from any living being, turning Godzilla into something unearthly that couldn’t, and shouldn’t, exist.

Both films hold off on showing the monster too soon. That’s partly because they don’t have Creature-level effects to work with. But no effects would be as effective as the ones that appear in the viewer’s head in the scene of a New Mexico cop walking offscreen and screaming in abject terror as he’s devoured. In a strange case of convergent evolution, when the monsters finally do appear in both Godzilla and Them!, they appear the same way, rising over the horizon, and it’s terrifying each time.

By now, we should all know what Godzilla looks like. Except he doesn’t look quite like that in the original film. For one thing, those aren’t scales. They’re burns from the atomic test that summoned him, and Honda has confirmed he studied the burns of Hiroshima survivors to create Godzilla’s design. This is one way Godzilla’s limited budget works in its favor. He’s not as solid or lifelike as the Creature from the Black Lagoon, but the awkward, ill-fitting suit also makes him look truly deformed: lumpy, asymmetrical, and misshapen.

If the suit’s different than it later became, so is the performance of Haruo Nakajima, the man inside it. In the sequels, he would move, if not with Creature-like grace, with the speed and ease of a five-foot man instead of a twenty-story monster. In the original, he lumbers ponderously, as if he really was carrying around tons and tons of weight. There’s other tricks Honda uses to make this Godzilla believable that apparently he and his collaborators forgot about when it came time to make the sequels. Like the classic Universal horrors, Godzilla uses long shadows and very little light, hiding the imperfections of the effects and making Godzilla’s burn scars reflect sickening, slimy light. If the monster movies don’t always deliver on the promise of “Screen-shattering thrills,” even at their worst they’re still good for some good laughs. And their best, they’re a powerful source of nightmare images that worm their way into your unconscious, and of the nightmares of the time projected from the collective unconsciousness and onto the drive-in theater screen.