I really like HP Lovecraft’s novella The Case Of Charles Dexter Ward (written in 1927). It’s a brilliant horror story structured like a cross between a detective thriller and a true crime report, starting with the facts presumably everybody knows – the eponymous young man was struck with a peculiar condition in which he’d lost much of his memory in exchange for an uncanny increase in overall intelligence, as well as aging quite rapidly, and has escaped from the local mental hospital – and then pulling back to describe how this all happened. Ward’s antiquarian interests lead him to discover his monstrous ancestor, Joseph Curwen, and his tragic downfall comes when he tries to recreate Curwen’s experiments, with the crowning horror being the full revelation of his crimes. It’s a masterful raising of tension; your initial clues as to what Ward and Curwen did indicate something terrible but fairly obvious, but the final chapters take a hop, skip, and jump into monstrosity far beyond what you could have guessed. If suspense is at its best when the consequences are four times bigger than the inciting action, perhaps mystery is at its best when the solution is four times bigger than the initial question. And the buildup to the solution is pretty great in itself, as Lovecraft expertly lays out the details of Ward and Curwen’s lives (very particular choice of words there) to cause maximum impact on the reader. It’s a Mad Men-esque storytelling device weaponised to create feelings of horror, pity, or disgust. It all comes together in those gripping final pages.

(SPOILERS from this point)

What’s truly interesting to me is how the story is also the culmination of Lovecraft’s life work. Charles Dexter Ward contains elements of so many previous stories that it feels like it was all practice for this. On a plot level, the climax of a character descending into an underground horror is an image Lovecraft had been drawing on since his first real stab at writing fiction, “The Tomb” (1917), and to which he returned in things like “The Statement Of Randolph Carter” (1919), “The Rats In The Walls” (1923), and “Pickman’s Model” (1926). Scientific necromancy is the premise of “Herbert West – Reanimator!” (1921-22). The idea of horrific gods worshiped by cruel cultists is an idea that dates back to “Dagon” (1917), “Nyarlathotep” (1920), arguably “The Music Of Eric Zann” (1921), and most famously, “The Call Of Cthulhu” (1926). Of course, references to the Necronomicon, written by the mad Arab Abdul Alhazred, are so replete as to be tedious to lay out. What separates Charles Dexter Ward from all of these is a specific command of pacing, doling out the information only as necessary. “The Statement Of Randolph Carter” gives us too little information for the horror to really land; “Herbert West” goes into so much that it just becomes gruesome as opposed to horrific. Charles Dexter Ward gives us just enough to spark the imagination, and then run roughshod over it. This basically comes from the fact that Lovecraft now knows what he’s doing.

I think of Bob Dylan’s line, “I already confessed, no need to confess again.” It’s like everyone has their own puzzle they have to solve before they can just, like, get on with things. Many of Lovecraft’s early works spend much of their wordcount describing the emotion he’s trying to evoke whilst being fairly light on the description; he parodied himself on this with “The Unnameable” (1923), and “The Music Of Eric Zann” is his most effective tweaking of that approach, conveying the effect of music through prose. But more often than not, it undermines rather than enhances the horror, telling the reader “This is very scary and you should be very scared of it”. At the same time, it often seems like Lovecraft is working out his philosophy as he goes – “Nyarlathotep” is a layout of Lovecraft’s burgeoning cosmic pessimism, “Pickman’s Model” is a defense of Lovecraft’s particular vision for the “weird art” he loved making and consuming, and perhaps the peak of this is “The Silver Key”, written shortly before Charles Dexter Ward, where Lovecraft lays out the emotional and philosophical journey he’d been on his whole life. Once he confessed his materialist atheism and his disgust with modernity (and modernism) and his love for the city of Providence, he could take it for granted and find out what comes after them. That makes Charles Dexter Ward as much evolution as it does conclusion.

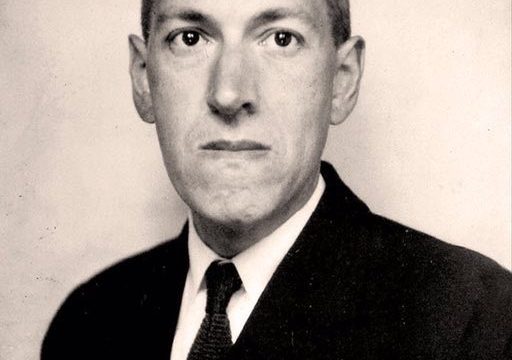

HP Lovecraft was a white supremacist, right up to his death. What makes him interesting (though to be clear not laudable) is how his views changed over his life. In his youth – definitely around 1917 – he passionately, fully believed that white British people were the superior race and that their culture had to be preserved lest the barbarians at the gates break in and destroy it all. His abortive move to New York (which was as full of people of colour in 1925 as it is now) seemed to seriously shake Lovecraft’s conviction in the immortality of white British culture, and at a point I’ve never been able to identify, he seemed to have come to the conclusion that the image of the 18th Century he’d had in his head never actually existed and his values weren’t as rooted in fact as he believed. He considered his values and found his cosmic pessimism kept winning out; “Call Of Cthulhu” was the beginning of his reassessment in story form, a realisation that his beloved white culture was as fragile as all the ones he, uh, didn’t like as much, and Charles Dexter Ward follows that thought all the way to the idea that someone Lovecraft would otherwise idolise – a pure white gentleman aristocrat scholar – could do things he would find abhorrent. By expressing and quantifying his feelings – by thinking of something horrifying and thinking about it in as intimate detail over the course of a decade – he eventually hit on two truths that extend out beyond the worldview of an elitist racist: a) our values are rooted not in any kind of ‘objective’ marker, meaning we’ll hold onto them no matter how abhorrent the facts of them are, and b) do not call up what you cannot put down. Our values, followed all the way to the end, can go somewhere terrible.

After writing this novel, Lovecraft would say that he held onto his conservative values not because they were inherently superior, but out of personal aesthetic preference and a fear of what would come if they were knocked down, and his writing would take a fairly consistent turn to the science-fictional – sometimes to its detriment, in the way At The Mountains Of Madness (1931) gets bogged down in the details of Antarctic exploration at the start. His moods were always present, always driving the action forward, but rarely would he feel the need to either explain or perform them; they would simply serve as the underpinning around which the world was allowed to revolve. They would even continue to mutate; three of his late-period works, The Whisperer In Darkness, At The Mountains Of Madness, and The Shadow Out Of Time serve as the rise, peak, and fall of a freaky alien civilisation in place of our own, with Lovecraft’s emotion shifting from panic, morbid fascination, and then ending in resigned acceptance. I often wonder what would have happened if Lovecraft had lived only another ten years. Would his decreased rigidness over his conservative views and increased fascination with alien cultures lead to him somewhere even stranger than time travelling cone-shaped aliens? And in turn, I wonder what I’ll be like in ten years. I’ve already noticed that spending the past couple of years refining my thoughts has paid off in unexpected ways. Will I look at “Home” the way I look at “Nyarlathotep” – something messy and thoughtful that had to be done to create a masterpiece?