They don’t make them like Spartacus anymore, an overstuffed, overlong pileup of gorgeous, funny, tearjerking, tearproducing, masculine, erotic, heroic, silly, stupid, insightful, manipulative, evocative, subtle, and overblown. It’s Kubrick’s longest film, and the one that’s least his–there are so many other voices and styles crowding for credit here–and yet it’s still more of a Kubrick film than most people (himself included) will notice.

Just looking at the credits and a bit of the history of its making, the authors of Spartacus would have to include: Kirk Douglas, who starred and was instrumental in getting it made; Howard Fast, who wrote the source novel (and wasn’t terribly thrilled with how the film came out); Dalton Trumbo, screenwriter (the first blacklisted screenwriter to come off the list and get a credit, and Douglas insisted on that); Anthony Mann, who shot the opening scenes; Saul Bass, who designed the titles (brilliantly, as you’d expect) and the battle scenes; and Laurence Olivier, Peter Ustinov, and Charles Laughton, major stars in Spartacus, all of whom had directed films and had strong ideas of how they should be directed. (Ustinov added some dialogue of his own, and I think Olivier did too.) Let’s also toss in Robert A. Harris, who supervised the restoration for the 1991 re-release and the Criterion edition. That it’s as much of a Kubrick film as it is tells us how strong his creative personality was.

Let’s get what’s bad out of the way first: the film lies down and dies any time we go to the romance of Spartacus (Douglas) and Varinia (Jean Simmons); in fact, it loses a lot of energy whenever Douglas has to talk. The dialogue between them ranges all the way from forgettable to embarrassing. Varinia doesn’t have any role in the overall plot, and barely any in the theme. She’s there so she can give birth to his son, who gets freed in the final moments of the film, and that’s pretty much it. OK, she does give Alex North a reason to compose one of the most memorable melodies of the 20th century, on which more Thursday.

A bigger failure is Trumbo’s and Kubrick’s inability to give Spartacus himself any personality. Lack of motivation isn’t a problem, as I have no trouble believing that people would be willing to fight rather than die as slaves. It’s that once Spartacus starts leading the uprising, he has only speeches to deliver, and none of them have got any poetry or force to them. (Trumbo can write great dialogue when he wants to; see below.) That poses problems for Douglas, who, as we saw in Paths of Glory, can do a great job portraying good characters but who still needs a character to portray. Often, he comes off as an entirely modern person reciting someone else’s words. You keep wondering where the smart guy we saw in Ace in the Hole went to. His best moments all come without words, or with a few words, like telling a Levantine pirate “get out” or in the deservedly legendary “I am Spartacus” scene, where the whole point is that he says nothing. (More on that later too.) Kubrick and Trumbo lightly explore an interesting possibility there: that Spartacus is more figurehead than anything else. That idea comes back in a few moments, but the story beats commit them to the idea of him as a heroic, romantic, and most importantly an active figure, so they can’t go down that road.

If Spartacus comes off as a weak character when he’s leading the slave rebellion, he’s much more effective in the film’s first (and best) hour, at the gladiator school of Batiatus (Ustinov). Here Kubrick can display his full skill with the dynamics and geometry of power. In addition to the steady horizontal pans of his previous films, he adds vertical pans, so effective when showing the gladiator’s cells; when Spartacus comes back to the abandoned cells, Kubrick paces it slowly and frames him in isolation. Douglas plays the scene silently and nearly unemotionally, and it’s among Kubrick’s best and most characteristic scenes. He paces the film so carefully here, speeding up or slowing down moments for maximum effect and tension, and doing so much with what we can see and can’t see. When Spartacus and Draba (Woody Strode) wait for combat, there’s another fight to the death going on, and Kubrick lets the whole thing play out through sound, through a single slit where Spartacus can see the action, and through watching their faces. Like Sergio Leone, Kubrick knows that whenever you can, just point the camera at Strode and let that face do the work.

We get in this hour the most Kubrickian character of the film, the trainer Marcellus (Charles McGraw), a former slave who Batiatus granted freedom. McGraw makes Marcellus completely confident in himself, and just a little bit strange. (He introduces himself to the slaves with “I like you. I want you to like me.”) There’s that military sense that he’s there to break you, and he simultaneously wants to protect you; it’s one more way in which this hour anticipates the Parris Island sequences in Full Metal Jacket. More than any other character, there are no politics to Marcellus. This man is a professional; more than any other character, he made his identity rather than inherited it.

Perhaps the best scene in the film gets played by McGraw and Douglas, as Marcellus literally marks kill zones on Spartacus’ body. Everything that’s great about Spartacus is in this scene: the framing, the vivid Technicolors, the professionalism of Marcellus, the silent acting of Douglas (his expression says “you know, sometimes being a slave just sucks”), and most of all, the objectification of beautiful men, because more than anything else, Spartacus is about the bodies of men.

Because Western culture is still so rooted in the (deeply stupid) idea of the mind/body split, objectification still gets a bad reputation; paraphrasing (I think) Michael Schudson, it’s a word that needs to be as complex as the thing it represents. To see people as objects means, on one level, simply to acknowledge the physical aspect of the world, and one necessary aspect of our world is its beauty. Spartacus glories in its beautiful, nearly naked men, the way they stand, the way they move; the lush Technicolor gives full range to all the colors and textures of skin, and Kubrick’s camera lingers over these bodies even more than in Killer’s Kiss or Day of the Fight. (If you’re looking for the objectification of women, you get one shot of Jean Simmons naked in a pond, with almost nothing visible.)

One horror of slavery is that it treats people not as objects but as commodities, as things that can be exchanged with each other or for cash. Kubrick and Trumbo nail that horror in the tense, funny scene when Batiatus leads Nina Foch and Joanna Barnes into selecting gladiators for combat (knowing two of them will be killed); Kubrick just keeps getting better at mixing his tones. The women are on a shopping expedition, sizing up the men and choosing favorites, and of course Batiatus tries to pass off the shortest, weakest men for them; Ustinov’s comic desperation is at its height here. Foch’s reading of the line “I’ll take the big black one” as she selects Draba suggests the banality of evil in a single sentence; she’s the Roman Lucille Bluth here. Later, as the fight takes place, the two women, Crassus, and Glabrus act exactly like those people watching movies in a theater who just will not shut the fuck up, and this is going on while two men are trying to kill each other.

On the level of plot, it’s a nice touch that Crassus’ commodification of bodies–setting gladiators to kill each other for entertainment, and buying Varinia–leads directly to Spartacus leading them in a breakout. Kubrick composes his best action scene yet, beginning with a fight between Spartacus and Marcellus. Douglas broke McGraw’s jaw in the fight, for real and on camera; I believe it’s Douglas who notes on the Criterion commentary that it’s the simplest stunts that are the most dangerous, because nobody thinks they need to be rehearsed. The bodies start running out of control, first with this fight, then by smashing the gates, and then overrunning Batiatus’ home and running into the hills. It’s visually thrilling, as each shot shows the chaos spreading wider; like so much of Kubrick’s great work, it’s precisely calculated and viscerally exciting all at once. The final, major battle scene isn’t as exciting, because there’s less of that sense of spreading disorder, but the lead-up to the battle (designed in part by Saul Bass) is fantastic, showing the precise, regimented order of bodies ready to be sacrificed, with, as in the gladiator battle before, Crassus watching from a distance; if the horror of slavery is the commodification of people, the horror of war is the instrumentalization of people.

Men’s bodies come back in another funny scene, and one that expands them from a visual aspect of Spartacus into a theme. Gracchus (Laughton), in conversation with Batiatus, remarks “You and I have a tendency towards corpulence. Corpulence makes a man reasonable, phlegmatic, and practical. Have you ever noticed that the nastiest dictators are invariably thin?” (I will never stop laughing at how Laughton hits that last word.) As Batiatus, Ustinov is plump, nicely rounded; as Gracchus, Laughton is a magnificent patrician blob. He looks more suited to sea rather than land, someplace where gravity is less of a big deal.

Gracchus’ line points to the most interesting conflict of Spartacus. The surface story is that of Spartacus’ uprising, and how Crassus (Olivier) puts it down; it’s the story of a slave vs. a patrician. Making the classic literary-critical move of taking a step back, though, shows a much more interesting conflict: Spartacus is about conflict between the idealists and the pragmatists, the buff men and the fat guys, Spartacus/Crassus and Gracchus/Batiatus.

Spartacus owes a lot of its intensity and interest to the way Kubrick, Trumbo, and Olivier make Crassus a full character. Olivier requested a false nose for this performance (the restoration creates at least one moment where this is really noticeable) and it both makes his face look more Roman and gives his performance a layer of, well, performing. Like George Macready’s General Mireau in Paths of Glory, Crassus is always performing, but unlike Mireau, Crassus has beliefs, smarts, and genuine courage. (Crassus gets blood on his face in his first appearance; you can’t imagine Mireau ever getting dirty.) Like Spartacus, Crassus is an idealist, holding the idea of Rome as his highest principle. “Rome is an eternal thought in the mind of God. . .if there were no gods, I’d still revere them.” He never once comes off as a hypocrite, and there’s so much more effort in characterizing him than Spartacus gets. And, of course, he’s as fit and as frequently half-naked as Spartacus.

Crassus’ two big scenes with his new slave Antoninus (Tony Curtis) keeps the theme of bodies going, not just because Curtis is easily the most beautiful man in the film. Done in longshot and through a screen, Antoninus bathes Crassus as the latter monologues about sexual taste vs. appetite, disguised as a discussion of food. (“Do you consider the eating of oysters to be moral, and the eating of snails to be immoral?” For reasons I can’t possibly explain, the 1960 censor suggested changing it to a discussion of truffles and artichokes.) The importance of the manner of sex over the object of sex (and its connection to other appetites and desires) was a key part of the Greco-Roman approach to sex; this scene winds up, intentionally or not, having a good deal of historical sense.

That scene points up the importance of Robert Harris’ restoration in the making of this Spartacus. It was cut from the original release and the audio from the footage was lost. Harris brought in Curtis to re-record his lines (you can hear thirty years’ worth of cigarettes in his voice) and Laurence Olivier, unavailable for reasons of being not so much alive, got dubbed by Anthony Hopkins, who clearly studied Olivier’s inflections on “mmm?” Also, if by some chance you haven’t seen The Celluloid Closet, watch it to catch Curtis’ reading of this scene: “. . .the guy’s a slave, he knows what’s coming, but he’s thinking ‘geez, buy me dinner first.’”

The following scene is the real payoff, though, as Crassus’ monologue shifts from love of men/women to love of Rome: “you must abase yourself before her.” That’s when Antoninus takes off, and Olivier gives a perfect little chuckle, like that’s happened before. Crassus will always be more comfortable with ideals than with men or women, and he gives the impression of having known that for a long time. Olivier’s Crassus embodies a truly classical sense of personhood–what you are gets chosen for you, you don’t make it yourself, and you have a duty to live up to that code. He’s a patrician, the guardian of “the Rome of our fathers,” and he lives that at every moment.

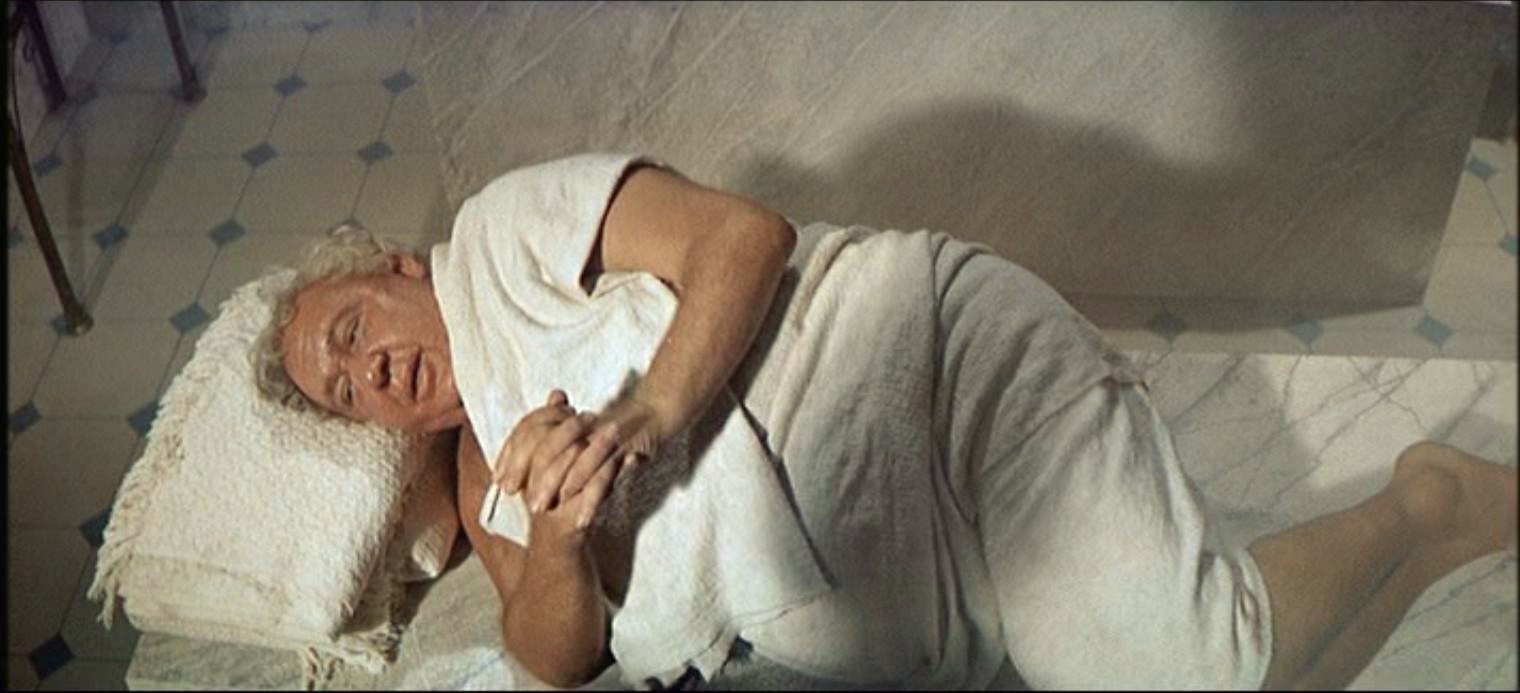

Crassus and Spartacus get played off against the pragmatists, the ones who don’t necessarily have ideals but try to get through the day as best they can. It’s another mark of Spartacus’ maturity that Batiatus isn’t a cruel guy; as much as in 12 Years a Slave, we understand that the cruelty isn’t a matter of people but of the institution itself. Ustinov, in his own words, plays Batiatus as one of his characters “who aim low and miss,” and it gives him a lot of comedy as he scrambles around, trying to please every master and get a cut for himself. As for Gracchus, we can see that he has convictions equal to Crassus or Spartacus; he has an amazing scene in the Senate where he just explodes. Gracchus believes in the people of Rome (the demos) where Crassus believes in the ideal of Rome. Gracchus makes the deals he needs to; he’s the expert politician caught in a world of crusaders. In his last moment, as he walks into the back of the frame to kill himself in his bath, Kubrick and Laughton create such a sense of sorrow, because Gracchus finally wound up in a situation that he couldn’t negotiate his way out of.

Part of what makes Spartacus a true epic are all the stories going on. Most contemporary films that claim epic status (Gladiator comes to mind) are simple stories told on a large scale, but this film crams so much action and so many characters into just over three hours that it actually feels like an edited-down miniseries. (It also has a lot of people who are barely characters at all, like Nick Dennis as Dionysus, aka Wacky Italian Guy.) Two of those characters, Caesar and Glabrus, create a vivid sense of generations in just a few scenes. John Dall plays Glabrus, Crassus’ protégé, as a genial, big-smiled moron; it’s impossible to watch him and not think of George W. Bush, the one who got to power entirely on connections and without ever once having to think about it. His reaction to getting played by Gracchus demonstrates one of Buster Keaton’s comedy principles: the audience loves a slow thinker.

More complex is Julius Caesar, who starts as Gracchus’ man and ends up with Crassus, which is to say he starts with the pragmatist and ends up with the idealist. (As Caesar, John Gavin has the body of an idealist.) He’s not as easily led as Glabrus, or really as anyone; he has the sense of being untested. That uncertainty loads Crassus’ final line with so much meaning, as he says to Caesar that he’s more afraid of Spartacus dead than alive, almost as much as he’s afraid of Caesar. (“Me?” “Yes, my dear Caesar. You.”) We don’t know, and neither does Crassus, just how much of an idealist this guy really is. Steven Soderbergh said once that endings are about beginnings, and Caesar’s story begins here.

Let’s not walk away from this movie without reflecting on its most famous scene, where after the final, massive battle, first Antoninus and then every other captured slave offers themselves up as sacrifice, shouting “I am Spartacus!” More than anything, what makes it work is the cut Kubrick makes between the faces of Spartacus and Crassus. Both of them are spectators to this moment; the agency belongs to everyone around them. Douglas’ face is in tears but determined; Olivier’s just falls apart. The Former Mrs. Wallflower described it best: Crassus realizes that no one will ever love him like this. Arthur Koestler’s observation “man is a reality, mankind an abstraction” lands in that moment. We see perhaps the strongest bond between these two idealists, because both of them see, without any sentimentality, what love means; not the love of the ideal of Rome or love of the ideal of humanity, but love of the man standing next to you. It’s a fusion of the practical and the idealistic that the rest of the film has placed in opposition. We can imagine a more rigorous, streamlined, more Kubrickian film about that idea, but from the glorious mess that is Spartacus, that scene and that theme has deservedly endured.

Previously: Paths of Glory (1957)

Next: Soundtracking #8: Spartacus and the early films