(In light of the two-pronged nature of Mike Mills’ latest project, I have decided to split my article on I Am Easy To Find into two; one on the short film, the other on the album.)

In The Thin Red Line, Terrence Malick began a practice of voice-over different even from the poetic narration of his previous two films. From then on, Malick’s narration emphasizes the collective nature of existence, cycling through narrators who speak their thoughts. Malick’s point isn’t that we’re all the same; we speak in different voices and experience different things. What he does believe is that we form one grand chorus of life, our experiences joining together to sing the song of life.

This may seem like a strange way to begin a review of the new album by The National, but only until you see that it’s produced and partially cowritten by Mike Mills, who’s a gen-X Malick with more of a sense of humor. Under his watch, The National have turned in I Am Easy To Find, an album broadcast directly from Malick’s Oversoul, a hymn about life and love in all kinds of different voices.

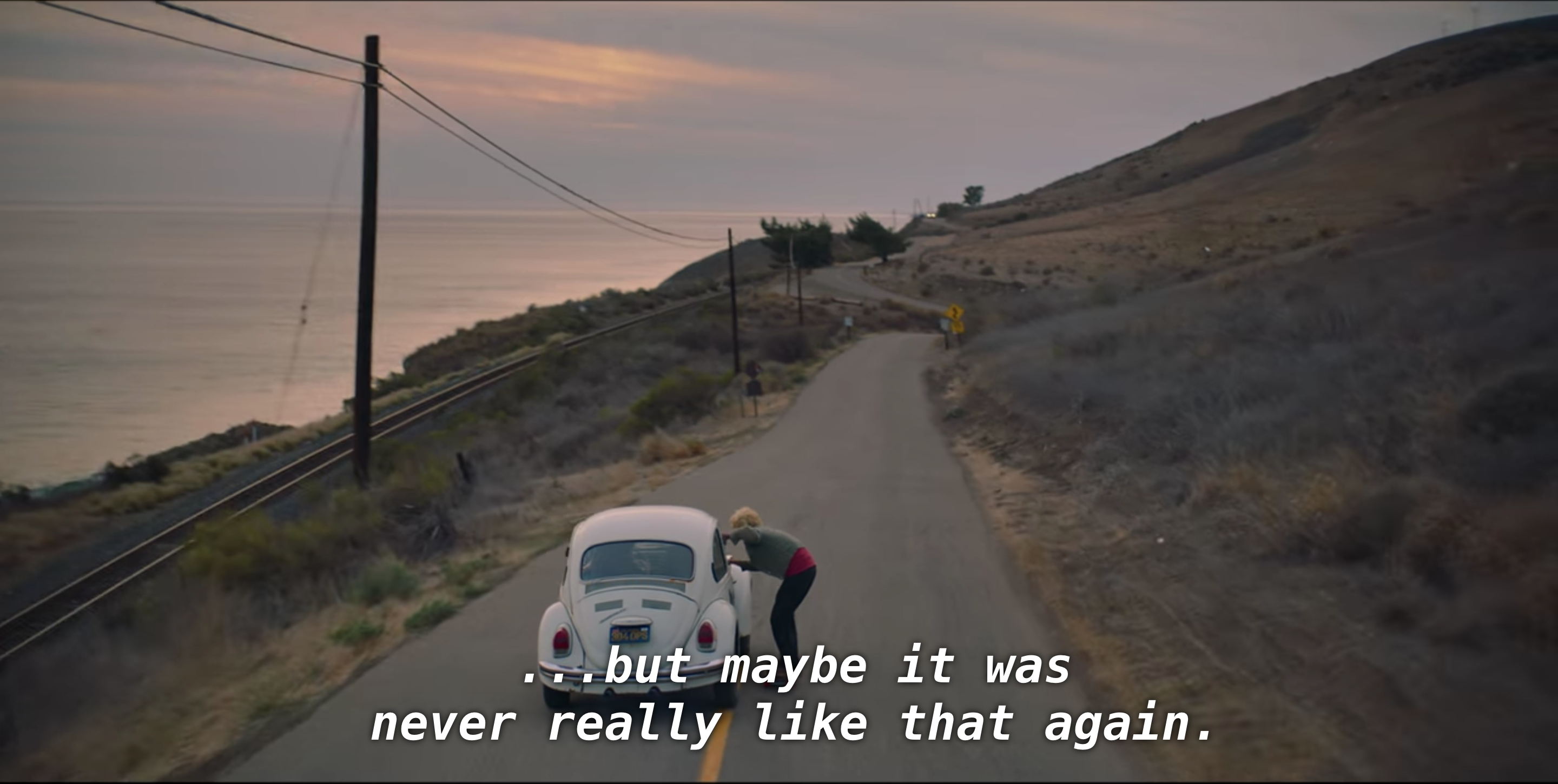

I’ll get this out of the way first: I Am Easy To Find the album is not neatly connected to I Am Easy To Find the film. The songs on the album featured in the film were, by and large, written around the time of The National’s last album Sleep Well Beast, and even the ones recorded in response to the film are unlikely to give you a clear synopsis of it (anyone expecting a song called “How Does It Feel When You’re Alicia Vikander (Good)” will be disappointed). There are a few songs that explicitly tie in, with “Where is Her Head” being centered around the words of a children’s book Mills wrote for the short, and “Dust Swirls in Strange Light” being a dramatic reading of some of the short’s subtitles by the Brooklyn Youth Chorus. But otherwise, the relationship between the two is more of a feedback loop than any kind of traditional companionship; the bulk of the album is Matt Berninger and Co.’s thoughts on life as inspired by a film of Mike Mills’ thoughts on life, which were already inspired by National songs inspired by yet more of their thoughts on life, and so on.

“Rylan”

Let’s begin with an easy-to-unpack example. “Rylan”, a song about a layabout longing to escape California, has been kicking around in National concerts since 2011, and there are only two lines changed from the live version to the album version. Before, the second half of the chorus went “Is it easy to seem so grand / Wanna be alone in La La Land”; now, it goes “Underwater you’re almost free / If you wanna be alone come with me”. The change in the second line in particular shifts the song from what was previously a lecture to an act of communion. Even with the specifics of Rylan’s existence, Berninger sees such a strong connection that them together is just Rylan alone.

The first line, meanwhile, suggests a stranger, knottier kind of alchemy. It ties into both the film and the album’s motif of being underwater (hell, the track immediately following “Rylan” is an instrumental called “Underwater”)… but the song already tied in with its lyric telling Rylan to “don’t let show any emotion / when you climb into the ocean”. If this lyric, even unconsciously, inspired Mills’ water imagery, then the song becomes an address to Mills. And maybe it was that in the first place, because the lyrics read like a continuation of the scene in 20th Century Women where Mills’ younger self is told by his older sister figure to get the hell out of California. The indignity of being stuck there working at a sunglasses shop is matched by the prospect of wearing “light blue and be[ing] forgotten”. Perhaps Mills saw this in the song and that’s why he had a female vocalist (British rocker Kate Stables, to be specific) take over the second half, in which the narrator asks Rylan “don’t you want to be popular culture?”. That’s as beautiful a summation of 20th Century Women and Mills’ work at large as any, finding joy and release in the idea of making yourself over in the image of your favored media. Perhaps Rylan will dye their hair red after seeing The Man Who Fell to Earth, or fantasize about a romance with Bogart in the afterlife. Of course, Matt Berninger could’ve meant this line as a joking suggestion that Rylan sell out, but Berninger isn’t the one in charge of the line now, is he?

Berninger and Besser

Berninger has long been the face of the band, not just as its singer but as an avatar for its brand of depressive-yet-polished indie rock. He has the voice of a well-put-together drunk and a disheveled demeanor despite always being tailored in a nice suit. But as emphasized by the publicity around this album, the sad-white-boy Berninger persona is in part a creation of Berninger’s wife, Carin Besser, who’s co-written many of his songs since Boxer. Berninger describes their writing relationship as them channeling their own voices and the voices of each other, creating an end result that may seem like Berninger’s straight-from-the-heart confession, but is really a swirl of different lives led. I Am Easy To Find is the first National album to fully utilize this relationship. This weird perspective that exists both outside and deeply inside Berninger and Besser fits perfectly for the voice of Alicia Vikander, someone who is at once herself and every living soul.

Even within the album, the addition of prominent female vocalists makes literal this kind of strange symbiosis. The vocalists aren’t here for hack he-said she-said gimmicks; more often than not, they’re picking up where Berninger’s words left off rather than rebutting them. But they bring out new details in those words, encouraging the listener of think of them as more than just the ramblings of a middle-aged guy. This is especially crucial in the album’s many songs that concern long-time relationships, where both sides experiencing the same struggle to stay committed to each other presents a more universal struggle than one guy’s whining. In the title track, Berninger and Kate Stables spend almost the entire song locked in harmony, both singing of the burden of heartbreak and the small comfort of knowing that the other person will still be “waiting for you every night with ticker tape.” It’s akin to the double-hander of 20th Century Women‘s narration, where mother and child express their love for each other while struggling to explain each other in the exact same ways. Human nature is the same halting, inaccurate words delivered in different voices.

Not that it’s all duets. Sometimes, the added voices go against Berninger’s in exciting ways. The opener “You Had Your Soul With You” deliberately sets up the entrance of Gail Ann Dorsey to be a breath of fresh air, Berninger’s neuroses giving way like the clouds parting in the sky, even if she’s not actually saying much different than what he was saying. “Where is Her Head” goes even further with the dissonance, delaying Berninger’s frantic ramblings about love until the middle and surrounding him with the English-rose vocals of Eve Owen (Clive’s daughter), speaking in the simple terms of a children’s book next to Berninger’s babble. She’s offering him a different way forward, a simpler means of understanding the people around him; where are her eyes? Where are her feet? Is she looking out? Given the misinterpretations all over the album, approaching someone on this literal a level seems like the safest bet to understanding them. Or maybe the solution is just to “stop being human” altogether, as the choir of voices sing when they interrupt Berninger’s stream-of-consciousness musings in “Not in Kansas”. Those words come from the Thinking Fellers Local Union 282 song “Noble Experiment”, but the original plays them as a dirge, while here they sound so heavenly as to be the word of God, telling us mortals that our time on this dying planet may mercifully be cut short. It’s certainly a perspective that’s understandable in this climate, and even if Berninger doesn’t go along with it (there are still several songs on the album following it, after all), he still leaves it on the table, as valid as anything else being said.

“That’s your version of me, that’s not me”

This is a line from 20th Century Women, one I referenced in the previous piece. What I didn’t mention about it either there or in the 20th Century Women article is that it’s Mills self-criticism. He admits in the commentary that he threw this line in there to admit that he, as a straight white male, might very well be coming from a perspective that’s misrepresenting the women in his life. And it’s especially crucial coming from Julie, who’s a composite character of many different women Mills once knew; it’s all too likely things got lost in translation when Mills made one human out of many.

I bring this line up again because it pops up twice in this album. First in “Oblivions”, about the lifelong commitment needed for a marriage, where the idea that “I am easy to find but you know it’s never me” presents a much sadder reality than in the film. Jamie only has so much time with Julie before they go their separate ways, but to spend an eternity with the idea of someone rather than their actual self is a grand tragedy (as Mills could likely attest, having lived with a father in the closet until his last five years on Earth). It then comes back in “So Far So Fast”, where Lisa Hannigan sings “what you think I am, it’s never been me.” It should be even more tragic, coming at the end of a relationship instead of the start, but Hannigan sings it with such wistfulness and awe that it’s so much more beautiful than sad. It’s maybe the most Malickian moment in the album, Hannigan seeing the grace in what should be devastating; she now understands that human nature is built around misguided ideas, and with that knowledge, maybe she can live a better life with this person. Her last lines in the song encourage her partner to “get away and talk to me”, so that an understanding may finally be worked out.

There are one more way the album ties into 2oth Century Women as well. In “Not in Kansas”, when Berninger admits to currently “binging hard on Annette Bening.” A fun nod, sure, but it starts to feel like it means more as the song morphs into Berninger begging for a mother figure to guide him through these troubled times; Dorothea Fields’ dinner parties seem like the inclusive ideal that America should be striving for. In “The Pull of You”, he wonders if he’ll go by being “carried to space by a dolphin balloon,” the same kind that floats above Dorothea’s head as she awaits death. He longs to be near her by any means, but hers is the one voice permanently absent from this tapestry.

The note the album leaves us on, “Light Years”, is a heartbreaker on any level, but its first verse levels me mostly because it reads unmistakably like a synopsis of the ending of 20th Century Women. There, the difference in perspective between Jamie and Dorothea becomes a chasm; we have come to the end of their adventures, and they are still worlds apart, and will only grow more distant with time and Dorothea’s death. They sing in harmony one last time, and are soon silenced. In the first part, Berninger, much like Mills/Jamie before him, realizes “the glory of it all” far too late, and is left to reckon with the fact that, no matter how long the relationship, he still never knew her.

But then the second verse comes. Suddenly, we are in a new scene, where Berninger sings of possibly seeing his subject’s mother in the park, or maybe seeing the subject, or maybe seeing no one at all. But still, the little bit of hope comes through, that maybe Dorothea’s ghost walks the Earth, or that Berninger is closer to his partner than he thinks, or that he finally sees the beauty of these other perspectives, even if it’s too late for him to do anything with that.

Conclusion

Thank y’all so much for bearing with me in these two articles. The short film and the album are two beautiful pieces of art that I can’t recommend highly enough, and Mills continues to present life to me in ways that change how I see the world. I’ll hope to see you sometime soon, whenever that movie Mills wrote while listening to Trouble Will Find Me comes out.