In 1998, Solaris was an experience barely known outside certain geek circles. As a science-fiction novel, it was still a Polish novel that only piqued certain interests. As a three-hour Russian film, it was still relatively unseen other than among film devotees. As an American film starring George Clooney, it still hadn’t been made. Yet, Solaris and Sphere have such similar plots that it wouldn’t be a stretch to consider this a case of trainspotting at best. Both Solaris and Sphere consider humans in a foreign habitat exploring an object of extraterrestrial interest and being plumbed for their worst fears. In Solaris, the astronauts are confronted with their past through subconscious hallucinations of their past. In Sphere, they deal with jellyfish and squid.

As a teenager in 1998, I certainly had not heard of Solaris in any capacity. But, I had read the best selling smash hit Sphere when I was 12 or 13, when I had a Michael Crichton kick. As such, my experience of the novel Sphere was that it was a perfectly acceptable twist on the Alien/The Abyss genre of alien space ship exploration representing something vaguely metaphorical about human nature. The novel may have plumbed the depths of everyday human cruelty, since the pain these benign scientists inflict is on each other rather than on themselves. I honestly can’t remember, and I haven’t read the novel since.

The movie version Sphere did not live up to anybody’s expectations, least of all those who really liked the novel. They say that comparing a novel to a movie is a fool’s errand, but Crichton’s novels are so basic that they feel like they should leap from the page to the screen fairly intact. The adaptations of Crichton’s stories up to this point had been relatively successful. Jurassic Park, Rising Sun, and Disclosure, content aside, were rather decent adaptations of their source material. Plus, the success of Jurassic Park had caused a Crichton fever in America, where every book he had written were constantly being discovered by new readers. By 1998, America had had two disappointing Crichton adaptations in a row, Jurassic Park 2 and Congo, and were already entering Sphere wary of what Hollywood would have done to destroy this semi-beloved novel.

Our first hints that Levinson’s Sphere may have missed the point of the novel are delivered right at the beginning, in the title credits. Consider that this movie is a present day movie about a crashed space ship at the bottom of the Pacific ocean which has a futuristic sphere in it that exploits the subconscious fears of anybody who comes in contact with it. Now, look at this drawing of a sailboat. The opening credits play out over a montage of old world sketches of sailboats being attacked by monsters and close ups of piranhas and other fishes with sharp pointy teeth. Sure, the credits and the images are distorted by a spherical lens reflecting and refracting in every which way to create some visual interest. But, this is the first sign that Sphere misses the supposed point of the exploitation of the subconscious in order to focus on being a monster movie.

Beyond the credits, the first 40 minutes of Sphere is a solid first act to an Alien knock-off. Dustin Hoffman and Huey Lewis open the film in a helicopter. Hoffman plays a psychologist, Norman Goodman [groan], who thinks he’s being flown to an airplane crash site to help the survivors. Lewis is flying Norman into the middle of nowhere somewhere off the coast of Guam, where a bunch of ships have gathered to investigate this not-a-plane-crash. Once Hoffman is on the ship, he quickly learns that the not-a-plane-crash is actually the discovery of an alien spaceship covered in 17 yards of Pacific coral, indicating it has been hanging out at the bottom of the ocean for 288 years.

In these openins scenes, Levinson gets to interject politics through the assembly of Norman’s team. Norman had written a bullshit report for the Bush Administration about what to do in the case that we find alien life forms. He recommends that we assemble a marine biologist (for some reason), an astrophysicist, a mathematician (math would be the common communication), and a psychologist (because the aliens would be confused). Since he named names, his friends are hired: Ted Fielding the astrophysicist (Liev Schreiber), Harry Adams the mathematician (Samuel L. Jackson), and Beth Halperin the marine biologist (Sharon Stone) who also happens to be Norman’s former patient. And, they’re all led by Navy Captain Harold Barnes (Peter Coyote). Beyond the obvious cronyism at work, Levinson’s political cynicism comes through Barnes declaring Norman’s half-assed report to be the Bible that this whole operation works under. Wah-wahhhh.

The opening shot isn’t actually the afore-displayed wide open shot. It’s actually a top-down close-up of the helicopter before it expands into the wide open shot. This kind of irrational playing with space is the downfall of Sphere. Potentially, as the crew descends into the depths of the water, their environment steadily closes in on them. But, in the name of realism, Levinson already puts everybody in tight quarters before they’re even debriefed. Levinson introduces us to three main characters – Harold, Ted, and Beth – in the tight hallways of a naval ship. These shots are played so close that Hoffman’s head even gets in the way and interrupts the screen.

The too tight framing of the naval hallways could be considered foreshadowing, but when the characters are debriefed in the next scene, Levinson returns back to a wider, more open frame composition. Levinson and D.P. Adam Greenberg are constantly alternating between claustrophobic and spacious framing, with little thematic rhyme or reason for why one scene is all close-ups and why another has the most empty space in the world. Perhaps it is meant to keep the audience disoriented, but the end result is that it looks like an amateur production from a first time director.

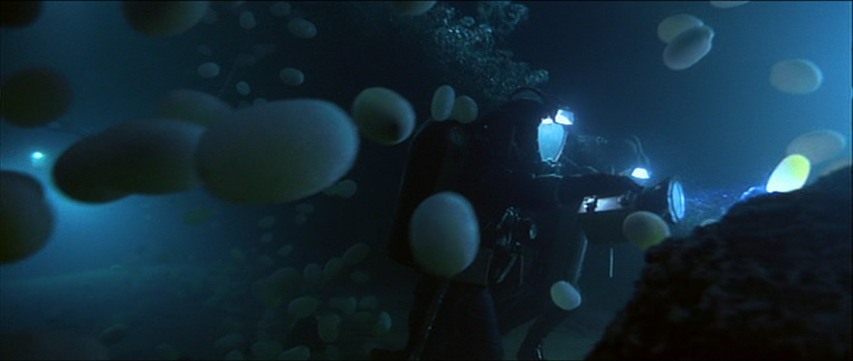

Anyways, the bitchy characters are finally debriefed and get in a submarine to go to the habitat underwater. In the transport sub, everybody is bitchy at Norman for pulling them into this mess, and Beth is a bit extra bitter because of her past with Norman. Things are about to get perfectly overdramatic when the sub finally makes a pass by the spaceship, interrupting the oncoming airing of grievances. The theme of Sphere is vagueness and distortion, and Levinson cashes in on that theme by utilizing vague and distorted special effects. The scale model shots of the space ship in the deep are filmed through a 2000 Flushes filter of dark water that barely show up on screen. I don’t remember it being any more vivid on the big screen.

Look, we all know this is an Alien rip-off, and Levinson was obviously trying to go for the same color scheme as Alien, but check out Ridley Scott’s clarity compared to Levinson’s reveal of his ship. Scott uses the same shades of blue color scheme to convey a sense of darkness, but Scott isn’t hiding his production skills. Unlike Levinson, Scott wants you to see the imagination of his team at work. This type of nod is the first of many inferior visual nods to Alien specifically. By the end of this sequence, all we know about this ship is that it is huge compared to the transport.

In the end, our team of

In the end, our team of assholes scientists finally shack up in the naval habitat at the bottom of the ocean. Similar to the above color scheme, the naval habitat has more than a passing resemblance to the Nostromo in Alien. The walls are alternately decked out in stitched padding and stainless steel, and whole rooms are lit using florescent bulbs. Even though this film is completely ripping off Alien throughout this point, Levinson’s techniques are still working on the audience, providing a sense of impending horror.

Sooner than the audience realizes, the crew eventually enters the spaceship. The first time the crew enters the ship, we’re only about 30 minutes into a 135 minute movie. At this point, the audience realizes that we have no clue what lies beyond the doors of the space ship, except that they’ll probably encounter a sphere somewhere in here. To Levinson’s credit, the mystery of the unknown is what keeps this first act afloat. Even through the forced terrible witticisms – upon feeling the door, Beth remarks “Is there heat coming off this thing, or is it just happy to see me?” – we’re still with Levinson on this rehash of Alien.

The very first sign that we’re in an American space ship is the crew’s discovery of a trash bin. They read the word trash, and that’s where this movie heads. The next discovery is of a dead body holding an individual packet of Blue Diamond peanuts (you have to have product placement somewhere!). The eyes sockets seem to have worms, but where the worms came from, I don’t know. Maybe we have worms in our body? Maybe they’re space worms. Overlook this detail because the creepy dead body signals a shift to a different frame of reference.

In 1997, another movie about an American space ship with a nightmarish sphere in the hull was released: Event Horizon. The sphere in Paul W.S. Anderson’s horror film was the ship’s hyperdrive that opened up dimensional rifts to allow the spaceship to make long distance jumps to the far ends of the universe. Upon boarding the Event Horizon, the crew discover a video diary entry straight out of Hellraiser. Its a horrific piece of found footage that has guts puking out of mouths and demonic voices. Sphere has similar lost entries, but they’re more mundane. This is a PG-13 movie, and so the worst we get in our scary video is an intergalactic black hole and a dimensional rift with the words WARNING and UNKNOWN EVENT on the frame.

Similarly, Anderson was more interested in creating a nightmare vision of the future with his sphere than Levinson. Event Horizon‘s Sphere O’ Doom was an shiny metallic ball with black spiked bands that circled it like a gyroscope in a room full of silver and black spikes. It was so goth it hurt. And, it was kind of scary as hell. By contrast, Levinson’s sphere is just a gold round CGI ball with a 1990s liquid gold texture mapped all over it. It’s more glam than goth, and seems completely out of place in the context of Sphere‘s knock-off Alien aesthetics, and for whatever purpose the Sphere has in the film. It doesn’t look otherworldly, it just looks shiny and made of liquid gold (the scientists say it looks like mercury, but mercury is grey!). Maybe it is meant to be deceptive and devious. A gold ball would be worth something, after all. But, greed never comes into play in this movie. Nor does desire. The driving emotions of the film are fear and curiosity. So, why a gold ball? We’ll never know.

When the team first discovers the sphere, they treat it with respect and awe. But, they leave it alone. It’s a first encounter. In secret, one by one, Norman, Beth, and Harry are attracted to the sphere. Harry secrets off and “enters” the sphere, by which I mean his reflection appears on the sphere and he disappears. Norman follows Harry and his reflection enters the ball. And, eventually Beth does the same thing.

In the vein of Kane from Alien (we’re back), when Harry returns from the sphere, he is unconscious for a long period of time. Eventually, he wakes up hungry as hell and ravenously eating copious quantities of food, especially eggs. Hilariously, he has a strong emotional reaction when he discovers the onion rings he was eating as actually calimari because he has a strong opposition to squid. Meanwhile, Queen Latifah has been attacked and killed by a bunch of jellyfish.

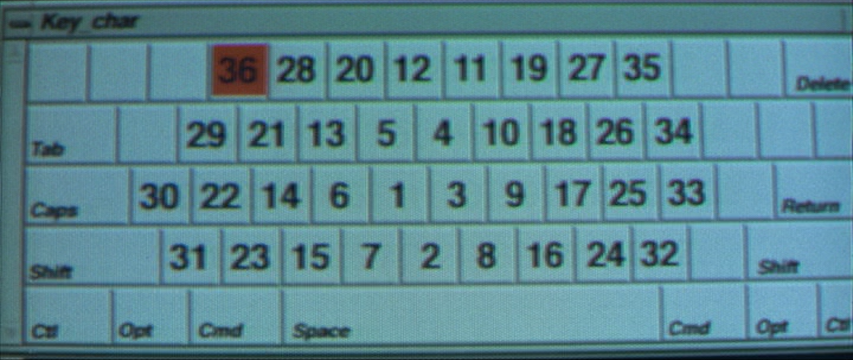

Trapped in the habitat, suddenly the sphere starts sending mathematical code at them. Through a hilarious series of logic leaps, they quickly interpret the code as a numerical representational of spherical reflection of an QWERTY keyboard. The first message, however, is hilarious. “Hello. How are you. I am fine. My name is Jerry. What is your name?” It’s basic, polite, and doesn’t lead with the chat room equivalent of A/S/L (What are chat rooms? ask your parents). The crew is now able to communicate with the sphere and vice versa. According to Norman, though, they have to be wary because Jerry, the entity of the sphere, has been trapped and lonely for 300 years and is now very clingy and desperate for attention.

Trapped in the habitat, suddenly the sphere starts sending mathematical code at them. Through a hilarious series of logic leaps, they quickly interpret the code as a numerical representational of spherical reflection of an QWERTY keyboard. The first message, however, is hilarious. “Hello. How are you. I am fine. My name is Jerry. What is your name?” It’s basic, polite, and doesn’t lead with the chat room equivalent of A/S/L (What are chat rooms? ask your parents). The crew is now able to communicate with the sphere and vice versa. According to Norman, though, they have to be wary because Jerry, the entity of the sphere, has been trapped and lonely for 300 years and is now very clingy and desperate for attention.

We’re only an hour into the film at this point. The remaining 70 minutes is a complete mish-mash of a wide variety of other influences. The crew is attacked by a variety of monsters, including giant egg-dropping squid and sea snakes. A giant squid attacks the habitat, breaking the outer barrier and causing fires. They discover that the sphere is actually connected to somebody’s subconscious, or everybody’s subconscious. And, they figure out that these things attacking them are actually imaginary even though they can kill?

In this vein, Sphere suddenly becomes a low-rent b-movie edition of Solaris, where a group of interspacial explorers have to face their greatest fears. Except, the fears of these scientists have absolutely nothing deep to say about the people. At most, the attack of an egg-dropping squid could be a hilariously on-the-nose symbol for Beth’s fertility, but nowhere does she say that she wanted kids. She was just screwing her psychiatrist, Norman, who also happened to be married and she’s a bit bitter about that. She also steps on one, perhaps hinting at an abortion, but this isn’t made explicit either. To make matters worse, Sphere strongly implies that the giant squid is Harry’s hallucination, and Harry is the one bombarding Beth and Norman with fertility eggs.

In this vein, Sphere suddenly becomes a low-rent b-movie edition of Solaris, where a group of interspacial explorers have to face their greatest fears. Except, the fears of these scientists have absolutely nothing deep to say about the people. At most, the attack of an egg-dropping squid could be a hilariously on-the-nose symbol for Beth’s fertility, but nowhere does she say that she wanted kids. She was just screwing her psychiatrist, Norman, who also happened to be married and she’s a bit bitter about that. She also steps on one, perhaps hinting at an abortion, but this isn’t made explicit either. To make matters worse, Sphere strongly implies that the giant squid is Harry’s hallucination, and Harry is the one bombarding Beth and Norman with fertility eggs.

Harry becomes obsessed with 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, of which he could only finish 84 pages. This is apparently one of his greatest regrets as his subconscious eventually causes hundreds of copies of the novel to turn up in the galley, each of which only have 84 pages printed in it and the rest are blank. To accompany Norman’s horrifying discovery that all of the food has been replaced by paperbacks of Jules Verne, one of the novels actually leaps out from the cabinet to attack him. Books are dangerous, yo.

Harry becomes obsessed with 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, of which he could only finish 84 pages. This is apparently one of his greatest regrets as his subconscious eventually causes hundreds of copies of the novel to turn up in the galley, each of which only have 84 pages printed in it and the rest are blank. To accompany Norman’s horrifying discovery that all of the food has been replaced by paperbacks of Jules Verne, one of the novels actually leaps out from the cabinet to attack him. Books are dangerous, yo.

Much like Solaris, the remaining three – Beth, Norman and Harry – eventually figure out they should get the hell out of dodge. They reach this decision in no small part because Beth hilariously set up a bunch of dynamite early in the film and set it off for the ticking clock finale. This escape is made all the more difficult because the sphere causes them to hallucinate that they’re not in the emergency escape pod even as the explosives are set to go off. They have to reach through their collective hallucinations in order to press the button causing their seacraft to go back up to the surface as the spaceship and habitat explode behind them.

When they finally reach top side, the finale is the best final laugh. Taken straight from The Simpson‘s 1997 episode The Itchy and Scratchy and Poochie Show, the three remaining scientists decide to collectively force themselves to forget about the sphere. They hold their hands and wish away their memory of the sphere. In return, the still-intact sphere rises from its underwater nest, out of the ocean, and flies away to return to its home galaxy. The end.

When they finally reach top side, the finale is the best final laugh. Taken straight from The Simpson‘s 1997 episode The Itchy and Scratchy and Poochie Show, the three remaining scientists decide to collectively force themselves to forget about the sphere. They hold their hands and wish away their memory of the sphere. In return, the still-intact sphere rises from its underwater nest, out of the ocean, and flies away to return to its home galaxy. The end.

The jukebox sci-fi movie wasn’t exactly new. The Italians had been perfecting the genre for decades through the 70s and 80s. Event Horizon had been Alien meets Hellraiser and was actually a great piece of schlocky horror. Later, Danny Boyle would make Sunshine, a compendium of pulpy horror and sci-fi tropes, using a self-referential wink that almost excuses the lack of originality in the face of an exquisite execution. With Sphere, however, the schlock is delivered with such earnestness that it becomes inexcusable.

In the face of such awfulness, the bigger question becomes, “is Sphere camp?” Some of the dialogue hints at intentional camp. Beth feels the door of the spaceship and asks “Is there heat coming off this thing, or is it just happy to see me?” Barnes asks for Jerry’s last name, saying, “I’m not putting in my report that I lost a crew member on a deep-sat expedition to find an alien named Jerry.” My favorite line is Beth commenting about an offer for coffee, “I’ll take mine black. Like my mood.” But, these pieces of trash dialogue don’t hint at a camp sensibility any more than they do an especially underdeveloped sense of wit. It’s hard to know who to fault for what in the awful production of this adaptation. Kurt Wimmer, eventual screenwriter of Ultraviolet and 2012’s Total Recall might be the easiest to blame, but he’s reduced to an “Adaptation by” credit. Screenwriter Paul Attanasio had his promising screenwriter career cut short by this movie after he had written Quiz Show and Donnie Brasco, finding himself on the rocks after Homicide: Life on the Streets finished filming. Or, possibly, screenwriter Stephen Hauser had moved quickly from production assistant in 1994 to screenwriter on Sphere, and then he disappeared from Hollywood (cursory research suggests he moved to Nashville).

Maybe it’s Barry Levinson’s fault. He was doing his best to elevate a crap screenplay by making it into a genuine horror movie. He managed to make a genuinely scary horror movie until it became too stupid to take seriously. A smart horror movie can sustain a 135 minute running time, but a camp reclamation struggles under such long-term criticism. The split sensibility between horror and camp really weighs down a movie, keeping it from becoming a fondly remember anything. The cultists want to like a movie unironically, but the camp class wants to laugh at a movie through and through. Sphere resists both efforts depending on the half you’re watching. It becomes a neutered movie, and ultimately an unfulfilling experience. Still, if you want a movie with A-list stars trying to tell you a batshit insane script without winking at the camera, you could do worse than Sphere.