Before helming Hereditary, director Ari Aster took an even more brutal look at family dysfunction with the excellent one-quarter-satire-three-quarters-Greek-tragedy short film The Strange Thing About the Johnsons. It’s just under half an hour and nearly impossible to discuss without spoilers as the whole plot turns on an early revelation; it’s available on Vimeo if you want to duck out now and watch it.

Spoilers will follow.

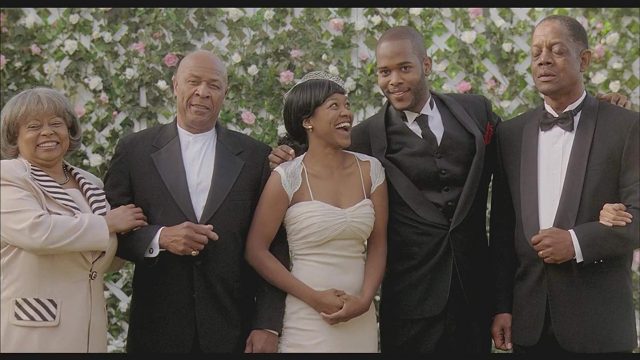

The Strange Thing About the Johnsons is set in an upper-middle class black family, in a suburban world with spacious lawns where decorous weddings can be held, in a milieu of light conversation with friends. (Even the title is suburban, framing the narrative as a kind of gossip.) Aster received some criticism for setting this sharp, bleak story of incest in a black family, but the choice is an interesting one, artistically grounded as opposed to just provocative. The undercurrent satire here is that the stuff of tragedy can’t be worked out of the fabric of human existence. The Johnsons exist squarely in the moneyed middle class, so their problems don’t stem from poverty, but they aren’t part of the traditional (and traditionally white) narrative of suburban secrets and WASP reticence, either. Aster’s not satirizing the idea of a functional black family, he’s taking aim at the idea that dysfunction is something that happens to other people, to people who are only either the recipient or the embodiment of social ills and pressures.

A father inadvertently walks in on his son masturbating. He backs out hurriedly, apologizing awkwardly through the door, and asks to come back in and have a talk. It’s excruciating to watch him earnestly slather on emotional openness as he tries to tell his teenage son that this is perfectly normal and it’s not something the son should feel guilty about and this incident isn’t something that should become an unspeakable secret in their relationship, a pocket of silence in which something could fester. It’s hard not to cringe with secondhand embarrassment, but at the same time, the father, Sidney Johnson (Billy Mayo), is, by modern terms, doing everything right. He doesn’t want his son to view sex as squalid and shameful. He believes in open, empathetic communication–though he does hit a wall of sorts when Isaiah (Brandon Greenhouse) asks him if he also “does it.” There’s a difference, after all, between “explain to your child that masturbation is fairly universal” and “explain your personal jerk-off habits to your twelve-year-old son,” and Sidney knows it. He flails and falls back into vague affirmation, “Everybody does.” (When we see Sidney’s books and realize that he’s a sentimental, popular poet along the lines of Billy Collins, it’s a perfectly chosen character touch.)

It’s awkward, sure, but it’s the awkwardness of doing the right, progressive thing. Emotional openness and mature conversation–those are, by modern doctrine, supposed to smooth everything out.

Except Isaiah is masturbating to a photograph of his father, and nothing here is simple. And as he grows older, and takes the upper hand, he molests and assaults his father for years, causing Sidney to retreat further and further into alternating fits of depression and terror. Joan, Isaiah’s mother, discovers the abuse but has no toolkit to deal with it at all. She retreats into willful ignorance, turning up the volume on the TV and sitting there with tears in her eyes while her son rapes her husband as punishment for locking the bathroom door, and if it’s a horrible, damaging strategy that helps no one, it’s in some ways a more coherent approach than Sidney’s. He burrows into self-help books about how your day will be determined by your own positivity, a thing his own life has already conclusively disproven; the phrases and rhetoric he clings to are ones his son uses against him. Talking about your feelings is, Aster implies, not an inherent good–it’s something that can be weaponized as easily as Joan’s silence. When Sidney tries an older form of talk–when he tries to write a confession to his wife–his son intercepts the manuscript and frames Sidney’s pain, horror, and shame as just, like, his opinion, man:

“I’m here now, and I’m in it, and I’ve given myself and I’ve accepted you, completely. But you’re not just my father. You’re my friend, you’re my best friend. And maybe we can just agree that that’s a beautiful thing, and not something to be perverted and corrupted and mutilated by your warped and confused conscience. You’ve always sabotaged everything good in your life. You’ve been shitting all over this from the minute it started. You never gave it a chance to be good.”

Sidney’s suicide after that point is inevitable. He’s caught in a tangle of his son’s rationalizations, and he takes the only noticeable way out of the Gordian knot. He runs out of words, and actions are all that’s left.

Joan runs out of silence, and words are all that’s left.

And the film runs out of narrative, and darkness is all that’s left.

There is a twisted grandeur to all this. The same beauty and savagery of the Orestes is also present at garden parties. If the message is that there is no way to stop bad things from happening to you, no sacred or sane combination of words and deeds that will protect you, then the message is also that you are more than your attitudes, more than your social contexts, more than your beliefs. You are whatever you do next.