Everyone knows Martin Scorsese loves New York City, but that doesn’t quite sum up all his feelings about it. A lot of commenters on here have referred to Taxi Driver as a critique of the anti-urban conservatism of the time, but I’m not so sure. I have no trouble deferring to my readers, who clearly know more about Scorsese than I do (which is unfortunate, since knowing about Scorsese is kind of my job). But looking at his gorgeous recreations of the past in New York, New York and Gangs of New York next to the cesspool Travis lives in, it’s hard not to see a bit of a decline narrative at play. As early as Who’s That Knocking, he pokes fun at his autobiographical heroes for preferring the concrete canyons of home to the searingly beautiful rural vista they see in New Jersey. He equates the city with hell pretty often too, from the subterranean smoke of Taxi Driver to the red-soaked lighting of Mean Streets to Gangs, where he treats the name Hell’s Kitchen as a statement of fact. And then there’s After Hours, about as literal a picture of hell as you’ll get in a Scorsese picture, set in the greatest city on earth in the time most people are most excited to be there. To outsiders, it plays as a paranoid fantasy, but Scorsese claims that locals have no trouble believing it.

He credits that believability to something he learned from Allan Dwan, who you may know from such Old Hollywood comedies as Getting Gertie’s Garter and Here We Go Again! (which I swear are real). He thought of those movies immediately when he saw Joseph Minion’s screenplay, and knew that he had to keep the movie going too fast for anyone to notice how impossible it all was. And oh, does it ever move fast. Roger Ebert said that The King of Comedy was so slow and the camera was so static that “it’s the kind of film that makes you want to go out and see a Scorsese movie.” This is that movie. Scorsese used to like slowing down the film, but now it’s all about speeding it up – the Benny Hill-style fast-forward of the hero’s cab drive into the underworld is like a bizarro world version of all those moody slow-mo shots in Taxi Driver. (Or, if you’re an arcade kid, a version of Crazy Taxi that takes the cake for Hollywood’s most faithful video game adaptation). Scorsese does tracking shots here like I’ve never seen them, jittery, racing things that look like there might be frames missing. The closest comparison I can think of is the “evil cam” from the Evil Dead movies, which I wouldn’t expect to be on Scorsese’s radar, but given that After Hours stars Cheech and Chong and the dude from American Werewolf in London, you never know…

A more likely explanation for the camera genius on display here is Scorsese’s first collaboration with Michael Ballhaus. All his films up to this point had been beautifully shot, but he had never found a dependable working partner and Ballhaus was the one: he would end up working on the majority of Scorsese’s films for the rest of his career. It’s easy to see why Scorsese took to him so strongly. The Variety review calls Ballhaus a “luminous lenser,” and I can’t think of any better way to describe the richly beautiful things he does with color. I said last week that Scorsese was a Technicolor filmmaker, and Ballhaus was the man he needed to bring his movies up to the standard of his father figure, Red Shoes director Michael Powell. That look would be essential for Scorsese’s epics in the future, and here the lurid primary colors and stagey lighting right out of Italian horror make After Hours’s New York a totally different kind of nightmare world than Taxi Driver’s.

And, as I alluded to earlier, Ballhaus could get impossible shots. There’s an early scene where Griffin Dunne as Paul watches a keychain fall to the ground. The keys fly through the blackness, and it’s a brief moment, but it was essential to the story. “Just for a moment,” Scorsese says, “he realizes that the keys could kill him.” It’s a gag about the gigantic keychains that were in vogue in eighties SoHo, and also the moment of clarity that foreshadows everything that’s about to happen. Ballhaus worked with a grips to invent a rig that could get the shot, even if it would have killed Griffin Dunne, the lead actor, if it didn’t work. “He had a European attitude to camera movement,” Scorsese says, referring to Ballhaus’s experience working with Rainier Werner Fassbinder on classics like The Marriage of Maria Braun and Fox and His Friends. “And it didn’t have to be perfect, it just flowed or flew.”

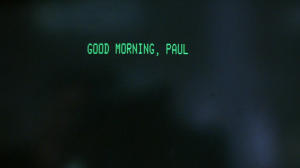

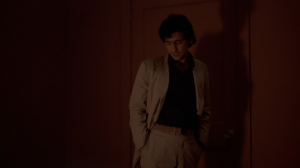

The collaboration didn’t just make the film better. It’s what it needed to work at all in Scorsese’s intention of making “an exercise in pure style” to shake off the cobwebs of financial and personal failure and the Sisyphean experience of trying to get The Last Temptation of Christ made. It reassured him creatively, and it was the first movie since Taxi Driver to turn a profit, but there’s nothing reassuring about the movie itself. Dunne plays a cubicle-bound worker drone who ventures downtown in the middle of the night in search of some tail and soon becomes the victim of an improbable sequence of guilt and bad luck. Scorsese says he’s never read Kafka, but I’m sure he knows his Orson Welles, and Dunne is more than a little reminiscent of Anthony Perkins in Welles’ version of The Trial. Dunne’s workspace wouldn’t be unfamiliar to K either, a washed-out fluorescent purgatory that Ballhaus shoots all in white and sickly green – another sign of modernity going under the microscope. He’s training a new word processor who lets slip that the last thing he wants in the world is to make a career out of working there. We see flashes of the little world Dunne is stuck in, and he seems to realize the trainee is right. At least, that may explain why he decides to venture through the heart of the city at a time Scorsese imagines he would normally be in bed. His apartment also establishes the kind of space he’s used to, a minimalist modernist wasteland, all flat surfaces with no sign of life breaking out of the right angles. So maybe he thinks the chaotic spontaneity of SoHo is just what he needs.

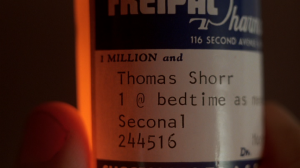

Well, obviously not, given what happens to him there. He should have seen it coming, too: besides the killer keys, there’s the cab driver, who Scorsese describes as Charon the Boatman, and his date’s roommate Kiki asks for his help on a papier-mâché man in the throes of Dantesque torment. His date, Marcy, as played by Rosanna Arquette, shows up late, and it’s something less than a dream date. To get over his nerves, he takes one of the joints that she had offered him earlier. But then, something strange happens. Instead of cooling him down, the joint leads him to throw a tantrum and storm out of Marcy’s room while she breaks down screaming and crying. I can kind of guess what’s happening – this little white collar man is coming out of his shell at the worst possible time, and letting out all his frustration, sexual and otherwise, on Marcy. And yet, it’s still shocking. He knows this woman is fragile – that’s what he’s mad about, and he handles the rage by directing all of it at her. “I don’t know what came over me,” he says, and he doesn’t sound convincing, but I don’t know either. But I know the consequences are fatal. In his previous films, Scorsese had made psychopaths, thugs, and raging bullheads relatable. So it’s somehow fitting that his everyman remains unreadable. Even in After Hours, the S&M freaks, Dorothy fetishists, gay men in leather vests or polo shirts, Bohemian artists and stoner burglars are all sane and normal. It’s the put-upon Average Joe who’s the weirdo.

Maybe Paul isn’t like K, the innocent man who never finds out what everyone thinks he’s guilty of. Maybe he came from somewhere else in the canon. From Shakespeare, say. Like King Lear, he’s more sinned against than sinning, but not by as much as he thinks. The punishment kicks in as soon as he leaves Marcy’s loft. As of a few minutes ago, the change in his pocket isn’t enough to get him home. He jumps a turnstile, and in a great bit of Chaplinishness[*], does a split-second 180 when he sees a cop on the other side. Of course, this isn’t the silent age, it’s Scorsese-style cringe comedy, so he keeps awkwardly making excuses as he walks backwards up the stairs. Through a long series of unfortunate events, he ends up back in Kiki’s apartment. When he gets there, he sees two burglars played by Cheech and Chong have bound and gagged her, except they haven’t. He interrupted her in the middle of an S&M session with a wonderfully, incongruously whispery-voiced leather titan named Horst. It wasn’t a total waste of time since Horst suggests he take the opportunity to apologize to Marcy.

Of course, she’s already killed herself by then. Ballhaus lays on the horror atmosphere here, putting the scene in dull red light that makes Paul’s shadow, or maybe his guilt, tower over him. And if you don’t believe me that he deserves just a little of what he gets, go on and listen to his impressively self-serving apology: “Ya know, I just figured… It’s not working out between us, and uh, hell, I’ll never see you again, and, you know, there’s just no excuse… I think I just got a little spooked, you know?… With that story about you and your husband. And your boyfriend? I mean, that was really weird. What was that all about?”

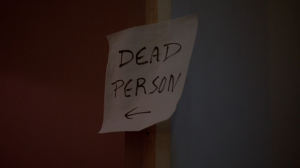

Not to mention that the first thing he does when he realizes she’s dead is strip off her blanket and look for burns. There aren’t any. But then, the catscratch scar we’d seen earlier is missing too. It’s the most purely horrific scene in the movie, but it also sets up the first scene to make me laugh out loud: Paul helpfully directs the police to Marcy’s body by writing “Dead person” on a series of paper towels with arrows pointing to her room.  That’s how the comedy works in After Hours: it’s what the producer, Amy Robinson, calls “dark scary funny stuff.” It’s not as funny a black comedy as King of Comedy, but it’s a lot blacker, and it shows that same thread of interchangeable comedy and horror that goes back to Scorsese’s very first film, What’s a Nice Girl Like You Doing in a Place Like This? Take an earlier scene in Marcy’s room. She’s just finished telling Paul her rape story when everything goes silent and the phone rings… and rings… and rings. It’s scary, but it’s so scary, and so quiet, and so awkward, that it’s hard not to laugh. The movie as a whole plays like an over-the-top parody of Hitchcock’s wrong man thrillers, where an even more whitebread protagonist gets tortured by even more relentless pursuers for crimes he had even less to do with. You can shiver, or you can laugh – Scorsese does very little to point in one direction or the other.

That’s how the comedy works in After Hours: it’s what the producer, Amy Robinson, calls “dark scary funny stuff.” It’s not as funny a black comedy as King of Comedy, but it’s a lot blacker, and it shows that same thread of interchangeable comedy and horror that goes back to Scorsese’s very first film, What’s a Nice Girl Like You Doing in a Place Like This? Take an earlier scene in Marcy’s room. She’s just finished telling Paul her rape story when everything goes silent and the phone rings… and rings… and rings. It’s scary, but it’s so scary, and so quiet, and so awkward, that it’s hard not to laugh. The movie as a whole plays like an over-the-top parody of Hitchcock’s wrong man thrillers, where an even more whitebread protagonist gets tortured by even more relentless pursuers for crimes he had even less to do with. You can shiver, or you can laugh – Scorsese does very little to point in one direction or the other.

As for the crime Paul does have on his head, he’s learned absolutely nothing from the experience. In another K-ish plot development (I don’t care if Scorsese’s never read Kafka, Minion obviously has), a total stranger becomes totally infatuated with him for reasons no one understands. That’s Teri Garr as “Miss Beehive 1969.” The closest thing he has to a friend, a bartender played by John Heard, encourages Paul to just blow her off. “What’s she gonna do, kill herself?” he asks, seconds before receiving the news that Marcy did just that. Paul tries not to replay the earlier situation, but he panics when he sees a mouse caught in one of the traps suggestively lined around Miss Beehive’s bed. She’d mentioned earlier that she works in a copy shop while she was sketching a portrait of Paul, and when wanted posters of him start showing up all over town, it eventually becomes clear why (I’m sure most of you figured it out sooner than I did.)

There’s a real paranoia at work here, the kind Kurt Cobain was talking about when he said “Just because you’re paranoid don’t mean they’re not after you.” There’s a specific direction the paranoia here, the fear of the effects our actions have on other people. Every human interaction is so complicated that it’s easy to imagine a thoughtless comment can end up destroying someone. Here, Paul’s carelessness leads to Marcy’s death and almost to his own, and even when he says something completely innocent, it inspires women to freak out at him. When he tries to commiserate with Miss Beehive’s job woes, she breaks down crying over every single anxiety she’s ever had, and in the rough cut this was mirrored in a scene where Catherine O’Hara wakes up the neighbors yelling at him for offhandedly suggesting she should leave if she hates the city so much.

Speaking of deleted scenes, the movie originally ended with the mob catching up to Paul in the basement of Club Berlin, and he had to hide in a woman’s womb so she can drop him off naked on the street. It was a product of desperation over an impossible plot to wrap up, and it violated the movie’s already thin connection to reality, but I’m still a little sad we didn’t get to see it, especially since Paul’s instructions include the wonderfully deadpan line, “It’s really all right if you have a waterproof watch on; just take it off if you don’t.” After discussions with everyone from Steven Spielberg to Terry Gilliam (in what must be the closest thing to a collaboration we’ll ever get from them) the crew came up with another way to end it. The woman hides Paul in a papier-mâché statue that looks suspiciously like the tormented creature Paul’s gotten to resemble more and more throughout the night. Cheech and Chong run off with it, and he falls out the back of their van – right in front of his office. The rebirth imagery is still there: the statue cracks open like an egg before he walks out.

Minion had already dropped The Wizard of Oz into the script when Marcy describes how she broke up with her husband (who, likely as not, is the bartender) because he kept shouting “Surrender Dorothy!” in bed, and it’s easy to see that movie echoed again right at the end. After dreaming of something better than his drab, colorless life, Paul gets transported to a Technicolor dreamworld full of exciting possibility, but it’s so harrowing that he decides he’s better off being bored. Or maybe not. The film ends with the camera whirling through the office, and as Roger Ebert points out, once we get to Paul’s desk, he isn’t there any more. What happened to him? What happened at any point in this movie?

Scorsese had gotten locked into a bit of a formula before making After Hours, having Robert DeNiro play mix and match with a set of character traits so often that critics were unsure he could do anything else. Combined with the years-long ordeal of getting Last Temptation made, he needed a quick low-stakes, anything-goes indie movie to get back on his feet. That was one way to keep working while chasing his impossible dream, one of the two options filmmakers take when things go belly-up. The other of course, is to take whatever the Hollywood machine will give you. As it turns out, Scorsese had time to try that one out too.

Up next: The Color of Money

* Pronounced chuhPLINishness, if you were wondering.