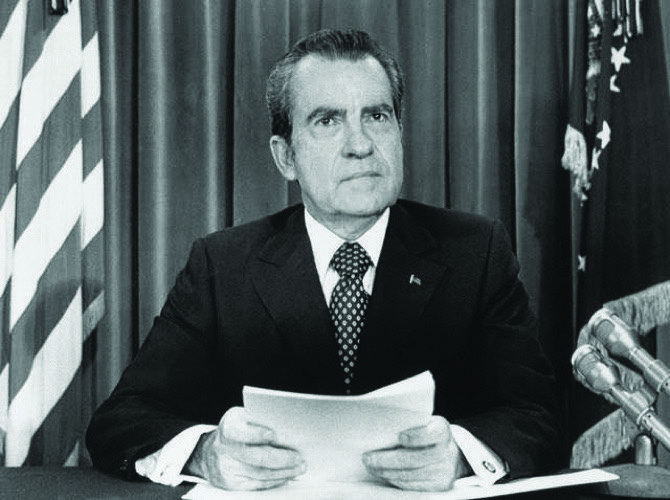

A moody Republican, long considered a national joke, is elected President of the United States on a platform of “law and order,” only to find himself embroiled in controversy over his abuse of power and official misdeeds.

That’s the plot of Thomas Mallon’s novel Watergate, published in 2014.

It’s also the subject matter of many American History classes since 1974.

It’s also probably something you’ve heard about in your particular corner of cable news or Twitter, spun in different ways depending on who you are and who you follow.

That’s what historical fiction is. It’s the facts you’ve heard, or maybe haven’t — the names, the dates, the events — filtered through a perspective and arranged into a narrative for the people of today; a work of fiction that adopts the conceit that the author can take you places you’d never be able to visit, inside the heads of people you’ve heard about but perhaps never regarded as fully human.

With every work of historical fiction, the author sticks their hands into a barrel of agreed-upon objects, details, an sources, and they sift. They sift looking for what they need and what they want. Out of a finite, closed loop of time and space they select those objects that strike their fancy and begin to do what they please with them. They may sand off edges, they may condense, clean up, censor, sensationalize, exploit or exaggerate. They can editorialize or attempt to remain “objective.” Unlike the author of other literary fictions, the author of historical fiction plays in an enclosed field: they are simultaneously restricted (to some degree) by the subject matter and the period, and given a boost, as they have real events to draw from for inspiration.

Historical fiction is all about those choices that the author makes. All fiction is, really, but what makes historical fiction interesting to discuss and to analyze is that we can, to an extent, see the creative process, because we can compare to both the real events and to the other portrayals of those events in fiction, culture, and memory. The choices are thrown into stark relief. The comparisons and contrasts can be seen naturally. All it takes is some research and some outside reading to shed light on an author’s choices.

The inaugural edition of this feature is about Thomas Mallon’s Watergate, and it should be a fine display of how an author chooses to construct their story with the facts that they’re given by the world to work with.

*****

If you grew up in the United States, you certainly know something about the Watergate affair. Maybe you lived through it, and can remember the televised hearings, the monumental court decisions, the public breakdowns. Perhaps you’re a history buff, with a personal library stocked with Haldeman diaries and Ehrlichman memoirs. Or maybe you know it primarily through its appearances in fiction: a classic film like All the President’s Men, or a modern classic like Spielberg’s The Post, or a modern non-classic like, uh, Mark Felt: The Man Who Brought Down the White House. It might be simply a buzzword to you, a vague idea of shame and scandal associated with a couple words (Nixon, burglary, crook) and nothing more. But you’ve heard of it, and it has some meaning to you.

So think for a moment. What happened at the Watergate Complex after midnight on June 17, 1972?

That part is not up for dispute. Five men were discovered while breaking in to the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee, and promptly arrested. The men had lock-picks, cameras, tear gas guns, a short-wave radio receiver, and several thousand dollars in cash. Two of the burglars were found to have address books on them containing an obscure but notable name: Everette Howard Hunt Jr. He worked for the White House. The Watergate Complex gave the scandal its name, but it truly began and ended in the White House.

Or did it?

Think for another moment. Why did these five men break into the Watergate in the very early hours of that summer night, all those years ago? The truth is, the ultimate purpose of the Watergate burglary has never fully been understood. Whatever the answer was, in clear and unambiguous terms, has been buried by official stonewalling, by self-serving lies and misinformation, by genuine confusion, by delusion, and by the memories of those who only saw a fraction of the big picture. Theories have been conjectured about who gave which order, about who believed what at what time. What did the burglars believe they were going to find in the offices of the DNC? It was money from the Cuban government, maybe, that lay at the heart of the whole thing — or, rather, the rumor of money from the Cuban government. Or maybe the money didn’t come from Cuban communists, but from American capitalists — maybe there was evidence of a secret loan from none other than reclusive billionaire playboy Howard Hughes. No, perhaps it was sex instead of money, the Republican operatives hoping to link Democratic big shots with seedy prostitution rings. Maybe there was no specific objective; it could have been simply a big risk for nothing in particular, that paid terrible dividends.

Thomas Mallon tries to answer that question with Watergate, and the novel serves as in many ways as a 400+ page fanciful daydream of what exactly would motivate such a stupid act. The answer, Mallon finds, was shame, tempered by love.

Love? In a story about Watergate? It’s a curious decision, but perhaps the most inspired in the entire novel.

The book begins and ends not with Richard Nixon, the larger-than-life historical icon, but with Fred LaRue, a lovelorn Nixon advisor who is the book’s heart and soul. You may be forgiven for thinking that LaRue is a fictional character: he was no great figure before the scandal, and was almost entirely forgotten after the scandal ended. LaRue was a conservative Mississippi oilman (hard to imagine any other kind) who became a Nixon campaign advisor, delivered hush money to the Watergate burglars, plead guilty, and served four months in jail. He died in Biloxi, Mississippi, thirty years after the resignation of Richard Nixon, and there was little to note about his life after Watergate. The most interesting thing about him was probably that on a hunting trip as a young man, LaRue was present when his father died from a gunshot.

From these scant facts, Mallon spins a web of personal neuroses and unrequited love affairs that the whole of the United States government ends up getting caught in. He doesn’t announce this up front, though — the opening chapter of the novel is deceptively quiet about how important LaRue’s decisions and backstory are going to be. In the first pages, LaRue gazes out the window of his apartment at the Watergate, puffing away on a pipe and thinking contentedly about how easy Nixon’s re-election should be. A TV plays: news about the President’s trip to the Soviet Union. The war in Vietnam seems to be winding down. The world staggers at the sight of Chairman Mao shaking hands with an old red-baiter like Tricky Dick Nixon. President Nixon seems to have done it all — he’s the War Candidate and the Peace Candidate all at once. A brief line about “the elegant bird gun mounted on the wall [. . .] not the gun with which Fred LaRue had managed to shoot Daddy instead of a duck” is the only clue the reader has to the importance and weirdness of this plotline.

In short order, Mallon’s POV characters are introduced: LaRue; Howard Hunt (the burglars’ boss and part-time spy novelist); the First Lady, Pat Nixon; Dick Nixon himself; and in an unexpected but utterly fitting choice, Alice Roosevelt Longworth, the 90-year-old daughter of Teddy Roosevelt, who lingers over the proceedings like a combination Greek chorus and Tennessee Williams protagonist, flitting back and forth between the past and the “present,” delivering bon mots, and serving as a living symbol of the old traditions of Washington.

What sticks out about these characters, in Mallon’s imagining of them, is how funny and how sad they are, often at once. It’s a bittersweet book, far from the frenzied psychohistory of Oliver Stone’s Nixon, or the procedural mystery of All the President’s Men. Mallon seems to have sympathy for all of the above, even Howard Hunt, who forged diplomatic cables, broke into a psychiatrist’s office, and once helped overthrow a democratically-elected government in Guatemala. Through Mallon’s pen, Hunt arises not as an amoral thug, but as a strangely quixotic character: a veteran CIA officers who seems to live as much in his lousy spy novels as in reality. And like Don Quixote, this Hunt has his own Dulcinea, in the form of one of the novel’s best characters, his beloved wife Dorothy, who is ambitious, unyielding, cynical, and far, far smarter than Howard. At one point, Howard Hunt confesses to his wife that he hasn’t thought of an ending for his next paperback. “Let the bad guys win,” Dorothy advises. When Mr. Hunt responds with “The bad guys aren’t supposed to win in this genre,” Dorothy counters with “Try bringing a little verisimilitude to the genre.”

Howard is devoted to her, in one of the novel’s several instances of personal commitments transcending historical judgment. The novel doesn’t deny Hunt’s crookedness, but that quality takes a clear backseat to his love of his wife, his loyalty to the other Watergate conspirators, and to his bizarre brand of personal integrity. Whatever else this novel thinks of him, it thinks of him as true to himself — an honor it doesn’t bestow on other characters.

If Mallon’s Hunt is compared to Mallon’s Elliot Richardson, it’s Hunt who comes across as the better man, which would have sounded crazy to all but the most fanatical Nixon supporters at the time. Elliot Richardson was briefly a Big Deal in American politics: a member of Nixon’s cabinet who stood up to the president and paid for it. As Attorney General, Richardson refused to fire the chief Watergate prosecutor, and resigned rather than abet Nixon’s crimes. He instantly became a household name, a by-word for dignity, and a potential candidate for the next President. Mallon’s Richardson knows all of this is going to come to pass when he resigns rather than fire the prosecutor. He delights in the idea of public adulation, and seems almost single-minded in his pursuit of fame, glory, and higher office. He’s self-righteous, self-serious, and self-aggrandizing. He oozes Old Money entitlement and Ivy League arrogance. If this is anything like the real Richardson, it makes Nixon’s well-known hatred of the ‘Eastern Establishment’ very understandable.

Mallon is a registered Republican who was appointed by George W. Bush to the National Endowment for the Humanities. The book is no right-wing screed, but it’s not hard, once you know what you’re looking for, to find the veins of a Republican outlook circulating throughout the novel. In addition to Richardson’s “sin” of betraying the President, the Washington press, one of the banes of Richard Nixon’s existence, is portrayed as little more than a collection of bottom feeders who go after Nixon for personal animus rather than for truth. There are jabs (not undeserved) at Nixon-antagonistic Democrats like House Speaker Carl Albert, mentioned only as an incompetent drunk, or Watergate Senate Committee chair Sam Ervin, whose hypocrisy as both a civil libertarian and a segregationist is mocked.

But at the same time, this is not Nixon apologia. Roger Stone will not be getting any passages from this book tattooed on him. What it is, instead, is an intimate and human-sized look at the Watergate scandal. This is not Watergate as epic tragedy, or Watergate as crime of the century. It’s Watergate as comedy of manners. In Mallon’s imagination, the real impetus of the Watergate break-in wasn’t a grand conspiracy or a hidden cabal. It was the personal foibles of Fred LaRue. Over the course of its narrative, Watergate gradually reveals LaRue’s motivation and how it plays into history. At the age of 29, LaRue’s father died in front of him on a duck hunt in Canada. LaRue was so traumatized by the event, which he mentally blocked out, that he refused to even look at the official report made by the Canadian authorities investigating the case, in fear that it would reveal to him whether or not he actually did shoot his father. LaRue had passed on the sealed Canadian inquest to his then-girlfriend Clarine. Years later, LaRue learns that Larry is working for the DNC, but has misplaced the envelope somewhere in the office. Scared of his secret being found out, LaRue orders Hunt’s White House “Plumbers” to infiltrate the DNC, misleading them into thinking Nixon needs the documents. In other words, the burglary, the indictments, the special investigation, the impeachment, the resignation, the course of history — all of it flows out from LaRue’s human weakness, cowardice, and fear of being shamed by society. It’s the small seed that grows a big tree. And it’s an interesting way to tell this story.

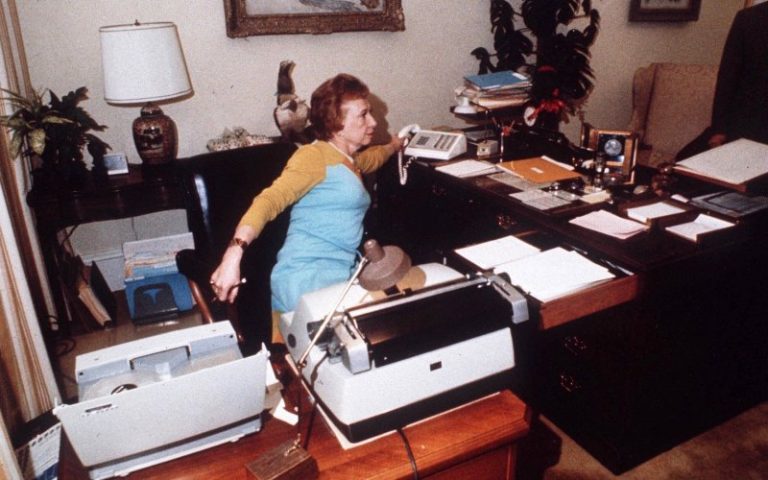

It’s in line with Mallon’s general approach — there is little in the story that’s not explained by simple human frailty or foolishness. What might be the most characteristic moment is later in the book, when Nixon’s dedicated secretary Rose Mary Woods is reviewing the White House tape recordings. When she hears Nixon and Chief of Staff Haldeman talking patronizingly about her (Haldeman says to Nixon “I never wanted to solder myself to you like Rose”), she’s embarrassed and hurt, and impulsively makes a decision that changes history.

“…fearing whatever she might hear next, she experienced a sudden fury, a desire to get rid of this tape […] She let the button up but then pressed it back down, five more times, until this whole personal, irrelevant, conversation was finished…”

And thus the infamous 18 1⁄2 minute gap.

Mallon’s view of the Watergate scandal is that it was a circus of dysfunction and unforced errors. Nobody acts villainously but nobody acts smartly either, and nothing can be attributed to malice that would not be more easily attributed to stupidity. One great sequence involves LaRue and his old flame Clarine having to convince an oblivious Howard Hunt to hand over the Canadian file by hinting at larger conspiracies, flattering Hunt on his importance, playing into his spy novel fantasies. Clarine adopts an exaggerated Ava Gardner femme fatale persona and lets Hunt think the file is the “Rosetta Stone” of government secrets. What looks ominous from a distance is in fact just blemished.

A recounting of the plot does little to convey the darkly comic cocktail party wit that Mallon employs throughout the book, popping through characters’ inner monologues, or in dialogue. When President Nixon counsels an indicted underling to ‘keep the faith’ during a phone call, he hangs up and thinks to himself “Christ: Keep the faith? Where had that come from? Adam Clayton Powell?” When Nixon’s even shadier VP Spiro Agnew arrives to the inaugural ball, Elliot Richardson remarks “A heartbeat away,” to which Henry Kissinger replies “And about fifteen IQ points.” When Pat Nixon informs Alice Roosevelt that LBJ has died, Alice responds “I imagine there’ll be loud grief in the animal kingdom.”

There are more details in the book than can fit here: Nixon’s recurring dreams of playing poker in his Navy days, wondering what bad thing is bound to happen next given his good luck streak; Rose Mary Woods’s office crush on Chief of Stall Al Haig; even Pat Nixon gets a secret intermarital affair with a fictional New York lawyer, someone who’ll show her warmth and gentleness compared to her cold president. This is a book of characters, first and foremost, and it can feel oddly frictionless, as it’s so committed to letting the characters comment on the action that it sometimes forgets to have action. The actual investigation of the cover-up doesn’t come until relatively late in the book, and once it does, the time seems to progress rapidly, one legal setback, one shocking revelation after another, until Nixon gets into that helicopter and flies off. In the final chapters, Mallon takes the reader through pivotal events over the next thirty years in the characters’ lives, ending with LaRue’s quiet death in Mississippi, just a local character once involved on the periphery of a major scandal he’d put behind him. The secret of Watergate dies with him. Well, except for us.

Watergate is not a great novel. For a novel about Constitutional Crisis, it’s strangely lacking in stakes and scope — by design, certainly, but the effect is still somewhat underwhelming. It’s observations are insightful but not brilliant, but it seems to be okay with this — its aspirations are modest. Despite its title, it doesn’t want to be the definitive take on the Watergate story. In fact, by beginning the story the way he does, in the Watergate Complex, with the small, undistinguished Fred LaRue looking at the blinking red light atop the Washington Monument as it peers over the city, the author persuades us to think of the story as a minor one in the shadow of something major. It’s marginalia, but it’s smart, well-drawn marginalia, with a sense of character, and of human fallibility facing the rush of history.