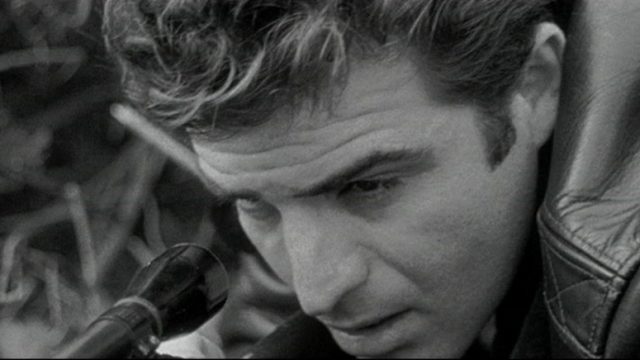

At the beginning of 1958’s Murder by Contract, we know only two things about Vince Edwards as its protagonist, Claude: he has a girlfriend in Cleveland and he needs money to cash out a house in New York. As the plot advances, we can deduce that one of these things is probably not true. For the first ten minutes, we see Claude planning to meet this objective by becoming self-taught mob assassin. Cooped up in a small apartment for two weeks waiting for his first assignment he orders takeout so as not to miss the call for his first assignment and does pull-ups to pass the time. After that, he provides his services with skill and anonymity. Then, over the next 70 minutes, Claude’s self-discipline and professional acumen are tested, not surprisingly, when confronted by a house and a woman.

For Claude, becoming a murderer is an existential choice, and he presents himself as an embodiment of the hitman whose job and persona are inseparable. The two seasoned gangsters who chaperone him on the aforementioned job find his coldly self-confident demeanor disquieting. Even for those employed in a line of work where violent death occurs with casual frequency, murder constitutes a resolution of a personal animus, not an ethos. One of the mobsters, Mark, nicknames Claude “Superman,”referencing the romantic egotism of Friedrich Nietzsche, not the comic book superhero. Claude is a killer who walks silently amongst the denizens of a lonely city, a particularly fifties s variant of the mass murderer as an archetypal marker of an alien consciousness.

The lone killer operating outside the strictures of urban heterosocial norms has been a fixture of mass public interest for nearly two centuries. The growth of cities during the Industrial Revolution fostered a sense of alienation as familial, religious and community bonds withered from economic change and the rise of new forms of political and social interaction. Some men couldn’t adapt to this transformation, and popular narratives began circulating from the pulpit and the yellow press blaming violence on the isolating effect of urbanization. Combining a flair for taunting the authority of Scotland Yard with a facility for concealment, Jack the Ripper transformed his fiendish acts of sexual compulsion into the subject of public interest. He embodied a quest for recognition harbored by legions of aimless men, strangers roaming among us in the dark alleyways of a terrifying new era.

The archetype of the lonely killer evolved over time, reflecting the time of his perpetual reemergence. In Fyodor Dostoevsky’s writings, that figure masked personal frustration as expressed in nihilistic Western philosophy. In Fritz Lang’s M, the abhorrent acts disrupt the fragile truce between the police and organized crime, forcing the latter to resort to vigilantism to retain order in the status quo. As the khe killer, Peter Lorre comes off not only as a victim of his impulses but as a catalyst for the suspension of the process of justice. The murderers in film noirs like He Walked by Night and The Sniper received training in their modus operandi from the military, with battlefield trauma and rejection (often by women) during peacetime triggering their homicidal fury.

In Murder by Contract, we get a dime store Dostoevskian tragedy built on a clash between Nietzscheanand Freudian modes of self-actualization. Claude channels his bloodlust into an entrepreneurial path, training himself to become an independent, professional killer, limiting social contact through isolation when possible and compartmentalization when necessary. He tries to be the utmost professional for the job, hogtying potential witnesses, checking to make sure he isn’t being tailed and mastering McGyver-like skills in turning household appliances into bombs. Yet he can be paradoxically cavalier, as when he spends a week on an L.A. job hanging out at his killing sites, blithely explaining to his chaperones that he needs to “clear his head” before surveying the area and mapping out a plan. Upon discovering that his target is a woman, he escalates the number of self-defeating actions that, as in all noirs, leads to his doom. Existential self-projection is no match for psychosexual dysfunction.

This is not a new development. The use of psychology to indict philosophical justifications for breaking moral commandments was a common trope in early mid-century American crime films. Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope and Strangers on a Train pretty much invented this tradition, and a year before Murder by Contract’s release, Richard Fleischer’s Compulsion dressed up the notorious Leopold and Loeb murder case (arguably the true-life inspiration for the motif) as a prestige courtroom drama. The interaction of the subconscious with objective reality, and the struggle to retain a coherent personality in the face of social custom, reaffirmed the irreducible substance of individuality over perceived threats posed by abstract ideologies. Emotion instills a moral balance that corrects excesses of pure thought.

What distinguishes Murder by Contract from these other movies is its low-budget aesthetic, and the ways writers Ben Simcoe and Ben Maddow, with director Irving Lerner, use the limitations of a one-week shooting schedule to visually and aurally bring this conflict to life. The constraints of the budget result in tight sets and exterior scenes largely devoid of extras or superfluous surface detail. Claude’s alienation is palpably expressed through a noticeable stillness and emptiness in his surroundings. For the interiors, small sets with minimal decorations create an air of escalating tension, highlighted by cinematographer Lucien Ballard’s hot lighting of blank white spaces on walls and doors. The unease generated by the intensity of refracted light forges an intimacy between the audience and the protagonist.

I must also cite the contribution of the film’s score to the overall effect. It is a spare, guitar-based variety of jazz themes composed played by Perry Botkin. While reminiscent of the zither used in Carol Reed’s The Third Man, the sparseness of orchestration serves an aesthetic purpose that further binds spectator to subject. The acoustic space around the music augments a hushed use of background noise, calling attention to itself by muting diegetic sound around it. In the same manner as the blazing whites of the lighting design visually isolate and scrutinize Claude , the music stands in pronounced contrast to the intensity of silence around it.

Like Claude, Lerner makes every aesthetic choice by the subtraction of what he deems irrelevant to his main point. The key element in a scene pops out, but the absence is also felt through a heightened awareness of absence. We experience this world through the lead’s character attempt to exercise power through intense focus. The narrative, however, takes us in another direction in which that power is taken away.

The influence of this film is significant. The consummate professional hitman re-emerged in Jean Pierre Melville’s Le Samourai in 1967. Like Lerner, the hard-boiled French auteur learned how to create intensity by subtracting naturalistic detail to highlight a key emotional center. The role of conditioning oneself to commit murder played a significant part in Martin Scorsese’s 1975’s Taxi Driver. That more florid movie challenges the assumption that the viewer’s morality is less alien than the protagonist’s as Travis Bickle’s emotionally cathartic violent outburst is celebrated rather than condemned. (The younger filmmaker later recruited Lerner out of the social science film library at NYU to supervise the editing of New York, New York.) Botkin’s guitar-based score shows up in Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man as well. More recently, Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin pushes the aesthetic of identification with the killer on the prowl into newer, more discomforting levels. In each instance, the sensational designs embedded in alienated aggression expresses some form of larger anxiety reflective of social change in an urban environment. Undoubtedly, the figure of the lone killer will continue to do so into the future.