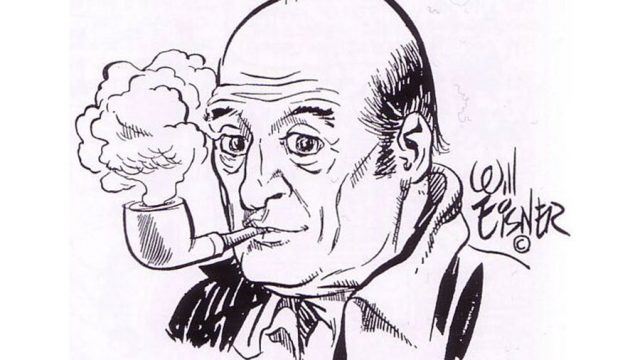

Will Eisner did not invent the term “graphic novel.” Arguably, he didn’t even invent the concept. However, there are a small handful of comics creators without whom the form would probably be unrecognizable, and Eisner is definitely one of those. Even though I suspect not a lot of people have actually read much Eisner—and the handful of movie and TV adaptations of his work have been, shall we say, uninspired—his creations have not only shaped the standards of the industry but have of course inspired enough other creators that the highest honour in the US comics industry is the Eisner.

Like so many other prominent figures in the entertainment business of his era, Eisner was born to poor Jewish parents. His father’s English was poor; his mother was essentially illiterate, as she had been forced to work from the age of ten, after both her own parents died. The family was culturally Jewish, but Eisner lost any devotion to the faith he might have had when a synagogue denied them membership for being unable to afford the fee. Regardless, ethnically and culturally Jewish was enough to cause young Will to suffer from the anti-Semitism of his peers.

One can only assume that his mother’s disappointment in his inheriting his father’s interest in art came from a hope that he wouldn’t be as poor as they’d been. His father was able to find some work painting backdrops for vaudeville and Yiddish theatre, but that was barely enough income to feed the family. That young Will was fascinated by pulp and drawing didn’t please his mother much. Still, even in high school, he was beginning to earn money at his art—which was handy, given the family was even more poor during the Great Depression than they had been before it. Though he did, with some financial regret, decline an offer to draw Tijuana Bibles at $3 a page.

You’d figure he wouldn’t have done what he did if he’d taken up that offer. Instead of drawing others’ characters, he drew his own. Encouraged by high school friend Bob Kane, he began submitting work to Wow, edited by Jerry Iger. The pair developed a successful partnership. Then, in late 1939, Eisner developed a character named Denny Colt, a police detective left for dead who lived in a graveyard and went by the name of the Spirit. Then he was drafted and started a successful partnership with the US military instead, where his character Joe Dope showed recruits how to use military equipment. Meanwhile, his trusted assistants ghost-wrote and -drew the Spirit.

In his later years, Eisner turned to more unusual work—semi-autobiographical works, a retelling of Oliver Twist called Fagin the Jew, a history of anti-Semitic tract The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. He taught art to others, mentoring other artists and shaping the field still further. It really is a shame that one of the only adaptations of his work is a version of The Spirit that doesn’t really understand its source material. I mean, I think the movie is funny in a ridiculous sort of way, but that doesn’t mean it’s a good adaptation in any way.

Help me afford some Eisner collections; consider supporting my Patreon or Ko-fi!