It’s strange that these movies came out in the same year. The Light in the Forest was released on the eighth of July, and Tonka was, obviously, Disney’s choice for a Christmas release that year. They are both concerned with the intersection of whites and Native Americans* in whatever the frontier was of its era—Pennsylvania in the former and Montana in the latter. I hadn’t seen either in many years, before this week, and I was worried about how well they’d hold up. Because, as we’ll get to next week, Disney and US history have not always been friends. And, you know, the ’50s were not a great time for screen treatments of anyone who wasn’t white. It turns out, though, that they both hold up better than you might have expected.

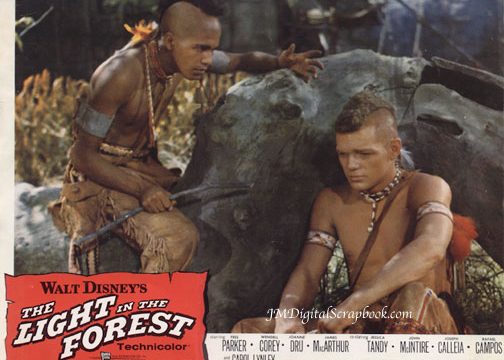

The Light in the Forest is apparently relatively loosely based on a book of the same name. It’s the story of Johnny Butler (James MacArthur), who as a four-year-old had been abducted by the Lenni Lennape and adopted as a replacement for a child killed by whites. He was given a name that I can’t find written down in my usual sources that translates as “True Son.” When he was fifteen, a treaty was conducted that gave all prisoners held by the Native Americans back to their white families whether they wanted to go back or not. And so the boy is returned to his biological parents, Harry (Frank Ferguson) and Myra (Jessica Tandy), in an area that’s known for its antagonism toward Native Americans. Even with the assistance of army scout Del Hardy (top-billed Fess Parker) and his burgeoning interest in indentured servant Shenandoe (Carol Lynley), things aren’t easy for the boy.

Tonka, on the other hand, is the story of a horse, loosely based on Comanche: Story of America’s Most Heroic Horse. A young Sioux teenager named White Bull (Sal Mineo!) manages to capture and train the horse, only to have it taken from him but the cruel Yellow Bull (H. M. Wynant). White Bull frees the horse, whom he’s named Tonka, rather than watch the horse suffer. Tonka is then captured by a band of horse traders and sold to Captain Miles Keogh (Philip Carey), who names the horse Comanche. Keogh is assigned to I Company of the Seventh Cavalry, and given that the movie is set in 1876, you don’t have to be psychic to see where this is going.

Both movies are a combination of fact and fiction. Some characters in each are historical figures, while others are not. Comanche was indeed considered the sole cavalry survivor of Little Big Horn (spoiler!), and he was indeed the pet of the regiment to the end of his days; he is one of four horses to receive a military funeral, and his taxidermied remains can be seen at the University of Kansas Natural History Museum to this day, if that’s your speed. (Actually, any number of horses and a dog survived as well, but the other horses were taken away by the Sioux; I have no information about the eventual fate of the dog.) It is also true that various tribes kept prisoners as members of the tribe and that, when they were told to return home, they didn’t always want to, even if this particular person is fictional.

Both movies also work very hard to teach the lesson that there are good and bad people on both sides. Both boys have to deal with someone who is their superior in their tribe who mistreats them, though White Bull has it worse, I’d argue. We never do learn why Yellow Bull doesn’t like him; it’s blamed on his losing of Yellow Bull’s rope and so forth, but it seems clear to me that Yellow Bull disliked him even before that. He just seems to be cruel. Whereas it’s pretty clear that Niskitoon (Dean Fredericks) sees True Son as more of a symbol than anything and resents having a white boy given treatment as a full-fledged member of the tribe.

Conversely, True Son has to deal with his uncle, his mother’s sister’s husband, the vile Wilse Owens (Wendell Corey). Wilse would quite cheerfully shoot the boy, and a thing I missed as a child is that Shenandoe is afraid of being raped by him. Wilse knows True Son is his wife’s blood relative and doesn’t care. Whereas the worst White Bull has to deal with from the white people is that, you know, there’s a war on, and he’s technically the enemy even if he is only a teenager. And Custer (Britt Lomon) was pretty awful regardless of which side you’re on. Both boys are given trouble by white men that other white men don’t like!

I suppose part of the issue is how personal their interactions with the other group are. As in, not very in a lot of ways. True Son’s biggest problem is that part of his moral structure is that the Lenni Lennape do not kill women and children, and Niskitoon sees killing as more efficient than taking prisoners, after Little Crane (Eddie Little Sky) is killed. White Bull’s biggest problem is, again, war. We see both boys spending more of their time with their own ethnic group.

I mean, sort of, and that’s definitely a place where these movies are Not Great. Interestingly, both of them feature Rafael Campos (born in the Dominican Republic); he is True Son’s best friend and adopted cousin, Half Arrow, and he is White Bull’s best friend, Strong Bear. Sure, okay, the whole point of The Light in the Forest is that True Son is Johnny Butler, White Man, but that doesn’t really excuse having Chief Cuyloga played by Joseph Calleia of Malta, who also played Dancer in the second Thin Man movie. I suppose having, sigh, Iron Eyes Cody as their technical consultant wasn’t entirely their fault; they probably thought he was whatever the hell tribe he was claiming at that moment. Though apparently that was inconsistent enough to challenge his story, and further I’m pretty sure all of his claimed origins were Plains, not anywhere near Pennsylvania, which explains why the whole thing felt wrong to me.

On the other hand, Sal Mineo’s redface is depressing. It could be worse—for a second, I thought one of the scouts late in the movie was Paul Frees in redface—but still, this was three years after Rebel Without a Cause, so it’s not like anyone was unfamiliar with what he actually looked like. Strangely, though, this is also the movie that casts an actual Sioux in the role of Sitting Bull, albeit John War Eagle, an actual Sioux who was, for reasons I’m not clear on, born in Leicestershire. Both movies have a scattering of Native Americans; both actually have Eddie Little Sky, come to that. Tonka appears to have more of them, but it doesn’t anywhere near to balance out the lead human role.

Regardless, I’d say both of these movies are a more interesting balance to the Cowboys And Indians narrative than most Revisionist Westerns. For one, they’re both aimed at older children—which might in theory keep them from internalizing some of the toxic narrative about the whole thing before it starts. They’re also the stories of teenagers figuring out how to be adults, which feels like dealing with a foreign culture regardless of your ethnic issues. And they do make clear that there are good and bad people on both sides; Del Hardy flatly says so. And White Bull and Keogh are able to bond over their love and appreciation for the horse, whichever name you use for him.

*Look, I’ve been very open about the fact that my problem with coming up with which term to use for this particular ethnic group is a lack of consistency within members of the ethnic group. There are plenty of people who would insist that I refer to the Lenni Lennape exclusively by that term and the Sioux exclusively by that one; others want Native American or Indigenous American or First Nations or even Indian. I recently saw two cars near each other in a parking lot being equally adamant about how the only proper term was [word], and they were using different terms. So yeah. I’m trying to be sensitive to the ethnic group’s needs on this one, but finding a single contrasting term to use regarding the People Who Are Not Of European Descent is not happening easily.

Help me keep renting films like Tonka to analyze for your amusement; consider supporting my Patreon or Ko-fi!