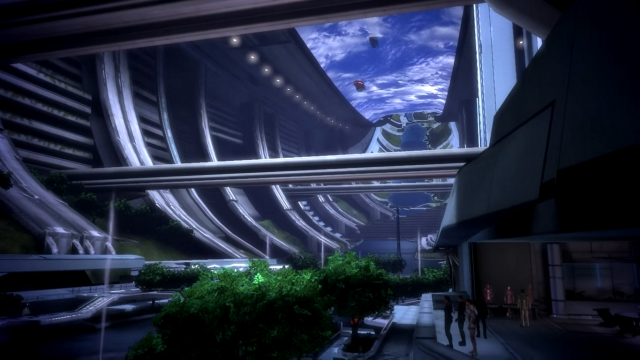

In terms of story, the Citadel is as if New York had the White House in it. I presume that Washington, DC has poor people in it, like any city, and I know that New York is supposed to have cleaned itself up (and gentrified) in the past two decades, but New York has become an American symbol for expensive decadence high above grimy slums. Up in New York’s skyscrapers are Gordon Gecko and Tony Stark, corporate deals and coke parties and prostitutes in slinky dresses. Down on the street you have Spider-Man, punks, drug dealers, and prostitutes in tacky miniskirts. That’s the kind of imagery the Citadel deals in. You have access to two sections, the Presidium and the Wards, and the Presidium is a sleek, bright, open area full of lakes and statues, very reminiscent of the times the various Star Trek crews went to Starfleet; you have to take an elevator down to the Wards, which are cramped and dimly lit and where the poor people live. The main purpose of Mass Effect – and I specifically mean the first game in the series, not the franchise as a whole – above everything else is to give you a world to play in, and the Citadel acts as an economic and cultural hub for the galaxy at large. One thing I heard that always stuck with me was that something often lost in discussions about the Hero’s Journey is that the whole point is that the Hero, enriched by his adventures, returns to the real world and enriches that in turn – for example, the hobbits go back to the Shire and become its primary movers and shakers for a generation – and that’s the general idea of the Citadel, the place where Normal People live.

In terms of gameplay, the Citadel acts as a breather between missions. With the excitement of “Expose Saren” behind us, the Citadel becomes like any other city, a hive of people and activity; it’s full of tiny sidequests that very rarely explode into violence and usually are solved by having enough Paragon or Renegade points – you could even see most of them as rewards for collecting enough moral points, because they’re often ethical questions where you pick an answer and back yourself up with sheer charisma. The most memefied one is when you come across a C-Sec officer arguing with a hanar preaching its religion without a permit; you can side with either the officer or the hanar. But I always liked the one where you come across a woman arguing with her brother-in-law over whether her baby should undergo gene therapy to deal with a potential heart condition that killed the baby’s father; it finds a real balance between being a Standard Ethical Question, a hard science fiction concept, a believably ordinary situation about believably ordinary people that neither belittles nor condescends to their perspective, and a chance for Shepard to yell at people like the badass iconic superhero she is, all without any individual aspect breaking any other aspect.

(The meme is Shepard inexplicably shouting “Because it’s a big, stupid jellyfish!”)

Not all the sidequests are ethical questions, though – there’s a fun little one where you find a gambling machine that’s funneling credits somewhere, and you discover a self-aware AI (illegal in this setting, as a response to the Geth) that tries to kill you. There’s also the mostly tedious story of the Asari Consort – generally, Mass Effect‘s creativity is based on finding a gap in recurring roles and examples in fiction, like, here is our Warrior Race, here is our space government, so this is a very rare example of riffing on one specific idea from one specific story. The Solute has collectively taken the stance that the Companions were the worst part of Firefly, and the Consort delves right into everything that was boring and distasteful about them without any of Whedon’s wit or personality. The gist of the story is that the Consort hires Shepard to talk to a turian general that’s started badmouthing her, and it’s like, you’re a mystical sex Yoda and yet this isn’t a problem you can solve yourself? The reward for all of this, aside from XP and money, are words of wisdom from the Consort as she delivers some keen insight into your character, but the lines she delivers (tailored to your backstory and playstyle) are generic platitudes. This game is at its most fun when it delves right into solid, clear worldbuilding and gives the player a chance to react to it; this is mystical, empty posturing.

It stands in stark contrast with the backstory sidequest. There are three potential backstories to Shepard’s life before the military; a “Spacer” can run across a soldier who knew her parents and has been reduced to a drunken homeless wreck due to PTSD, an “Earthborn” will be approached and blackmailed by members of the gang she used to run with, and my “Colonist” is called in to talk down a survivor of the Mindoir attack who was enslaved for thirteen years. Each of these little stories gives you a chance to characterise your Shep based on how they react to their backstory. Do they carry it with them, or did they walk away? This question is most violently answered with the “Earthborn” story, where Shep can literally tell her past to fuck off, but it also factors into the way she can describe how she did or did not move on from Mindoir. I always took great Mad Men-esque pleasure in matching up Shepard’s declared worldview with the rest of her actions, but even without that there are simple emotional pleasures to these missions, like the beautiful line Paragon Shepard gives the survivor before handing her a sedative (“You’ll dream of a warm place. And when you wake up, you’ll be in it.”), or the despair as Shep’s mum’s friend has going into rehab.

There are also missions that are just simple ownage for the sake of ownage. Another memed sidequest is when you’re approached by a hack journalist intent on smearing Shepard and the Normandy, and you can choose to play politics and present the Normandy as a win for diplomacy, or you can criticise the Council’s handling of the whole situation, or you can just punch her in the face. You’re a Spectre, which gives you certain freedom from consequences (although my Shepard is a fucking professional and chooses diplomacy and not to comment on the current fucking mission). I also get a kick out of the surprise inspection from Rear Admiral Mikhailovich, an admiral philosophically opposed to the very existence of the Normandy on both a diplomatic and tactical level, and your job is to defend your ship. Interestingly, it’s another example of the game being a power fantasy but deliberately limiting itself; no matter how well you do, you’ll never actually change Mikhailovich’s mind, and what you’re actually convincing him of is that you’re using the ship as well as it can be used. That edge of plausibility makes it a greater power fantasy for me – having charismatic power over stupid people is a lot less entertaining than having charismatic power over smart people.