Scorsese had been there at the peak of rock and roll, as an editor and cameraman on Michael Wadleigh’s Woodstock and here he is in the valley. The Band had been working in their field just about as long as Scorsese had been behind the camera. But the road had aged them prematurely: he’s a fresh new voice, a kid with a camera. They’re veterans, with all the shellshock and exhaustion that implies. As the title implies, The Last Waltz is about the end of an era, but most of the principals don’t seem so sad to see it go as they do be involved with it in the first place. Looking at the movie twenty-five years later, Roger Ebert sees the Band as “survivors at the ends of their ropes. They dress in dark, cheerless clothes, hide behind beards, hats and shades, pound out rote performances of old hits, don’t seem to smile much at their music or each other. There is the whole pointless road warrior mystique, of hard-living men whose daily duty it is to play music and get wasted. They look tired of it.”

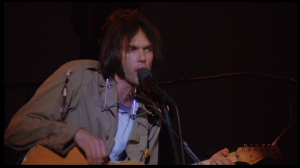

The end of an era means the beginning of a new one, and the concert’s extensive guest list is a good mix of acts losing their relevance, like their old boss Ronnie Hawkins, ones who remain timeless like Dylan and Young, and ones just coming up like Emmylou Harris. The movie is a time capsule in many ways, but especially in the way it shows how low the standards were for rock star glamour were in 1977. Neil Young, especially, looks barely put together, a shambling, slack-jawed character with crazy, unfocused eyes and a greasy hair.

And then there’s the Band’s Richard Manuel, a stoned, deranged mountain man whose eyes and teeth peek out from under his dark eyeborows and thick beard like a wolf through the trees.

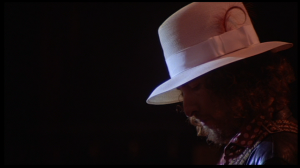

Van Morrison is almost comically shlubby in his purple sequined coat, and Bob Dylan, looking quite a bit younger than his protégés, wears a giant cowboy hat that would give Pharell pause, especially since the stage lights make it look pretty-princess-pink when he first comes on stage.

The movie opens with Robbie Robertson hunched over a pool table, looking just as haggard and ancient as Paul Newman would in Scorsese’s pool epic The Color of Money. He keeps on playing, if “playing” is a fitting word for something he takes so little joy in, as the sound of a cheering crowd bleeds in from another scene and the Band takes to the stage. Scorsese makes his influence felt most clearly in these early scenes, with a drive through the moody streets of San Francisco, taking special time to look at the wrecked cars by the side of the road.

Or the moment when the Band is introduced, their names hanging under their faces like the kids in Mean Streets. And an abstract, Fellini-inflected title sequence isn’t the kind of thing you’d expect from a rock doc, but here we are, with a couple dancing in the blackness until they uncover the words The Last Waltz, keeping in step to the dance of the title, played by the Band but sounding more than a little like something from the mind of Nino Rota.

Even in a situation that doesn’t give him much to do, Scorsese still fills the film with plenty of stylistic flourishes. He prefers to shoot the performers from behind, the better to show the play of light on the stage. The Last Waltz is full of dark, shadowy figures glowing under misty light, and Technicolor lens flares framing them as he shoots them from the back. Neil Young may look rough, but his collaboration with the Band on “Helpless” is transcendent, not least because of Scorsese’s cinematic embellishment. He frequently cuts to a backup singer backstage (maybe Joni Mitchell?), a black silhouette of the kind that’s made an appearance in his last three films framed against the curtain.

He shows some of the same interest as he did in Italianamerican of preserving the scenes where his interviewees aren’t quite “on,” including a moment where Robertson flubs a question and Scorsese asks him if he’d like to start over. Of course, that also made him an easy target – this little kid from New York looks so out of place next to these country-rock gods that it’s easy to see how he inspired This is Spinal Tap’s Marty DeBergi. But that’s also part of his charm, especially when he asks Levon Helm about a subject that’s near to his hear, even if it’s not very relevant to the matter at hand. Helm ends up giving him the definitive description of visiting the City: “New York, it was an adult portion. It was an adult dose. So it took a couple of trips to get into it. You just go in the first time and you get your ass kicked and you take off. As soon as it heals up, you come back and you try it again. Eventually, you fall right in love with it.”

Besides, there’s other moments that other documentarians would leave on the cutting room floor that are essential to The Last Waltz’s impact. The most striking is in the performance of the Band’s big hit, “The Weight” with the Staple Singers, when, after the song is already over and it would be easy to move right to the next one, Scorsese captures Mavis Staples whispering, “beautiful,” before a soft fade to black. His style here isn’t perfect, though. Especially in the first half before the movie really builds up steam, Scorsese relies on long takes that neuter the energy of the performance, and even though he opens The Last Waltz with a title card saying “THIS FILM SHOULD BE PLAYED LOUD!” I have to wonder if that’s to compensate for how quiet it is on the visual end.

The performers are the real stars here, anyway. When the young bucks in the Band seem all used up, it’s especially memorable when the most energy in the show comes from a little sixty-year old man from Mississippi. That would be Muddy Waters, and even though he mostly stands in one place, eyes closed trancelike, and shaking his hands like a revival priest, he commands everyone listening to dance. He may look older than the beardy kids backing him up, but his voice hasn’t aged a day.

There’s other scenes of rock and roll power coming from unexpected places. Another guest, who I had never seen before, who lends some stunningly soulful vocals to “Dry Your Eyes.” When he walks off and someone names his as legendary middle-of-the-roader Neil Diamond, it plays like a punchline. Joni Mitchell’s vocals are angelic of course, and so are Emmylou Harris’s, in a scene filmed on a soundstage after the Band’s alleged last performance.

Paul Butterfield makes the harmonica sound just as awesome as a Fender Stratocaster for the blues banger “Mystery Train.” Van Morrison may look like a doughboy, but that only makes it all the more amazing to see him belt out the lyrics to “Caravan” like the souliest soul man that ever sold soul.

Dylan is brilliant of course, with his performance of “Forever Young” directed right at the heartstrings. It seems like a perfect closer, but the film tops it by bringing everyone back onstage (along with some new faces, like a very jolly Ringo Starr) for a great big community singalong of “I Shall Be Released.” There’s something fitting about that. In all their interviews, and more subtly in their performance, the Band seem to see the end of their career as a release. That kind of escape was still out of Scorsese’s grasp. Reeling from a flop and in the depths of drug addiction, he needed to see that light come shining, from the west down to the east. He had another documentary on tap, about old friend and fellow druggie Steven Prince. And his next narrative film got him clean, both physically and professionally. Which one is up next? Well, as someone unacquainted with the worthwhileness of that documentary, American Prince, I’ll let you tell me.