Comics history, like all history, was written by the winners, and in this case, the winners were the superheroes. The Golden Age of Comics produced a lot of great superhero stories, but it was also a widely diverse time, full of genres ranging from romance to horror, historical adventure and war stories. And the most popular, and frequently the best, were the humor comics aimed at younger readers: even in the superhero genre, the best seller was the comedy-oriented Captain Marvel (returning to theaters this year under the name Shazam!), who outsold even Superman, and Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories outsold them both. And the best of them all were written by John Stanley.

Stanley’s best-known, as far as he’s known at all, for the definitive kiddie comic, Little Lulu, but he was extremely prolific even beyond that series. He wasn’t allowed to sign his work for most of his career, but fans have still been able to create a complete catalog of his work by identifying his unique style, his personal themes, and his idiosyncratic vocabulary of cartoon sound effects — “Baw!” for crying, “Choff, choff, choff” for eating, and “Yow!” as an all-purpose exclamation. Working for Dell Comics, he wrote the adventures of characters like Tom and Jerry, Woody Woodpecker, Raggedy Ann, Alvin and the Chipmunks, Krazy Kat, and Nancy and Sluggo (who, as you should know by now, is lit). But in 1961, Dell lost its partnership with Western Publishing, and with it, access to the license portfolio that provided them with most of their material. They had to come up with original series to keep afloat, and so they commissioned Stanley to launch his own. He gave them Thirteen Going on Eighteen and Around the Block with Dunc and Loo, as well as his one attempt at the soap opera genre with Linda Lark, Registered Nurse. These series would be joined in 1962 by the short-lived beatnik comedy Kookie, the one-shot Nellie the Nurse and a stretch into another unfamiliar genre with the horror one-shot Tales from the Tomb and the inaugural issue of Ghost Stories. (Despite Stanley’s efforts, Dell eventually went under. That’s bad news for them, but good news for you since these comics are all in the public domain and available to read for free at the links above. Or, if you want something a little more tangible, Drawn and Quarterly has released an excellent hardback collection of Thirteen Going on Eighteen.) Altogether, that’s nearly 700 pages of comics, all wildly different, but each showing the unique spark of an overlooked genius.

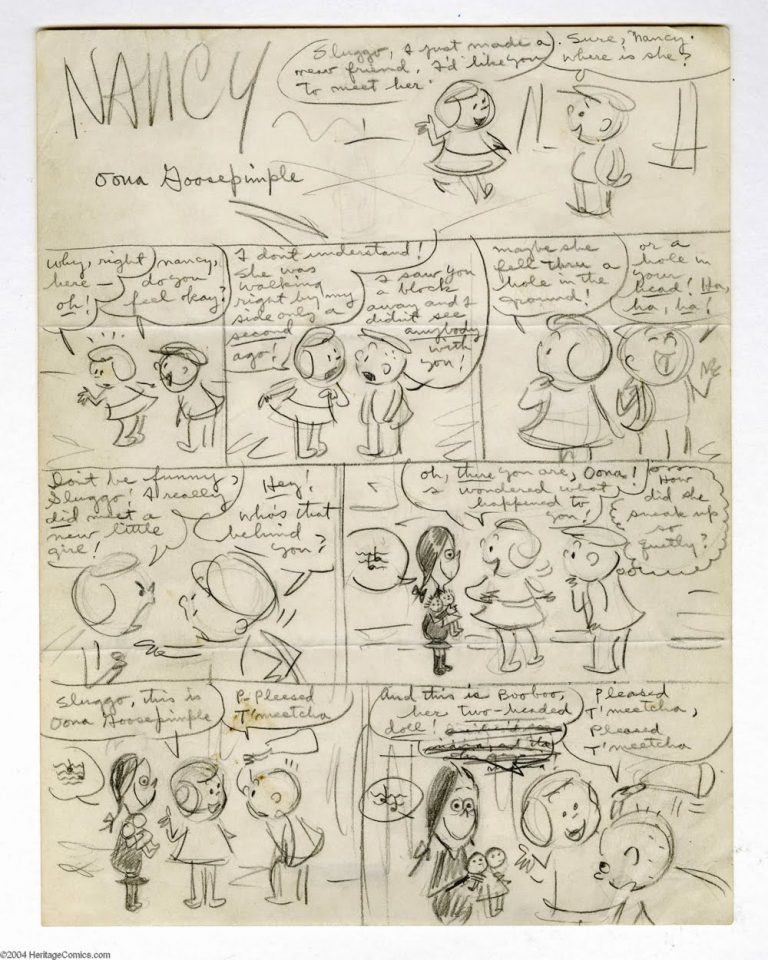

That 700-page count looks even more impressive when you know how he wrote them. Even though Thirteen’s the only one he pencilled and inked himself, Stanley wrote his scripts as detailed “storyboards,” making him the de facto artist behind all these comics.

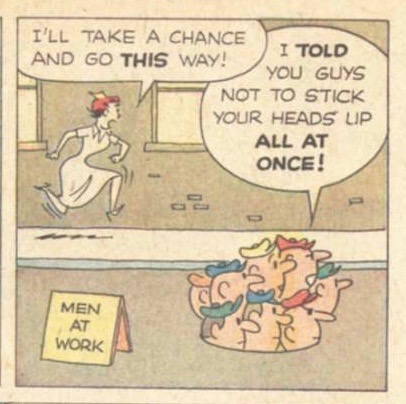

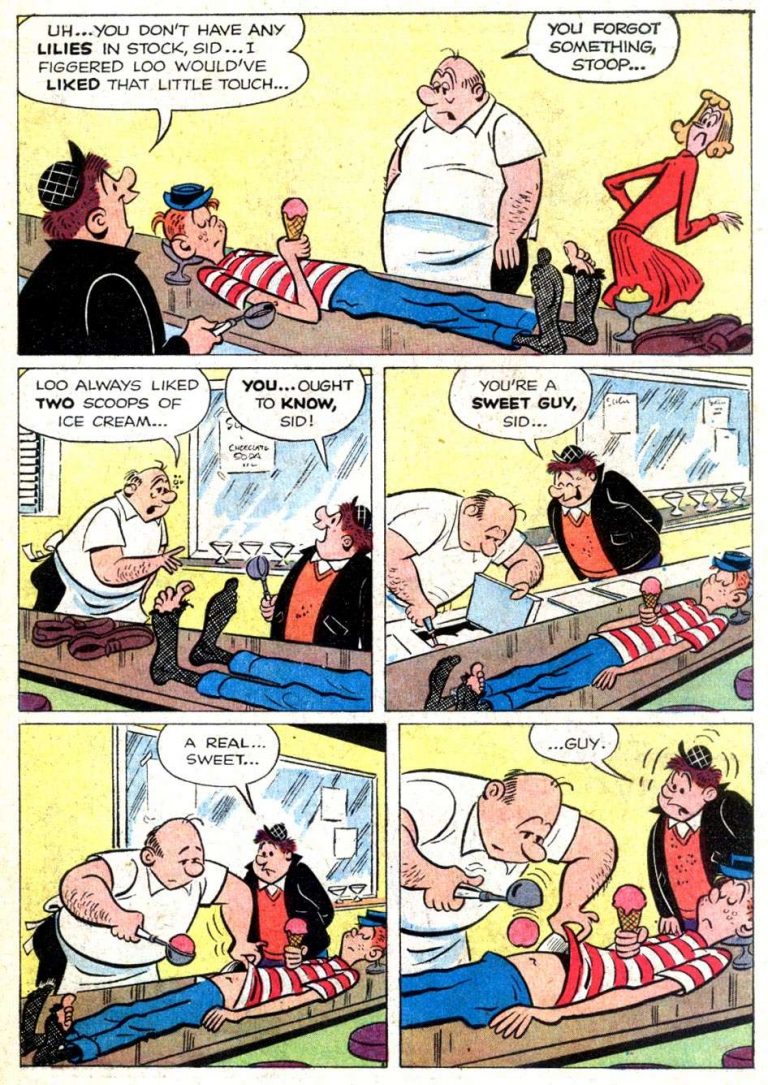

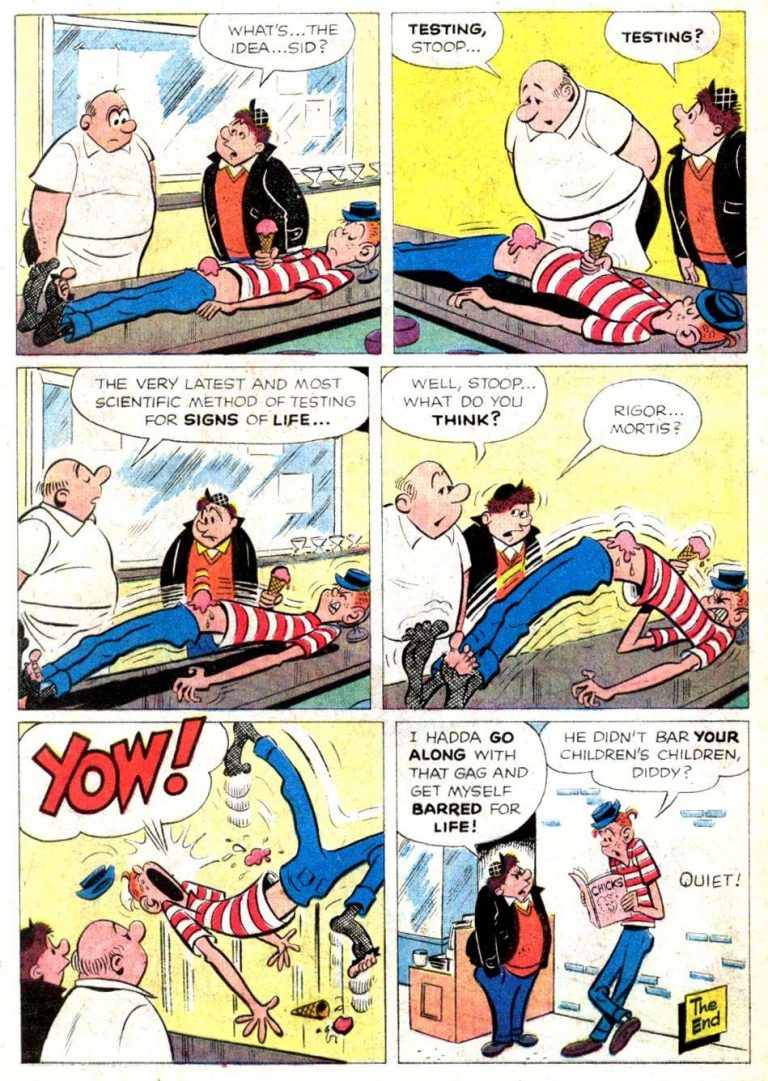

Even among his humor series this year, Stanley was working across a wide range of topics, with characters from early childhood (the “Petey” backup feature in Dunc and Loo and the “Judy Junior” backups in Thirteen) through tweenhood (Thirteen) and teenhood (Dunc and Loo) to adulthood (Nellie and Kookie). Even working anonymously, there’s a variety of personal touches that tie all his work together. The most notable is his comic sense. Stanley was an absolute master of the opposite extremes of manic slapstick,

deadpan absurdity,

and, frequently, both at once.

Like many comic artists of his generation, Stanley came from animation. He had been an inker at Popeye’s Fleischer Studios, and that may explain the cinematic precision he brings to his slapstick setpieces, which can slow down the action over a page or more without ever losing momentum.

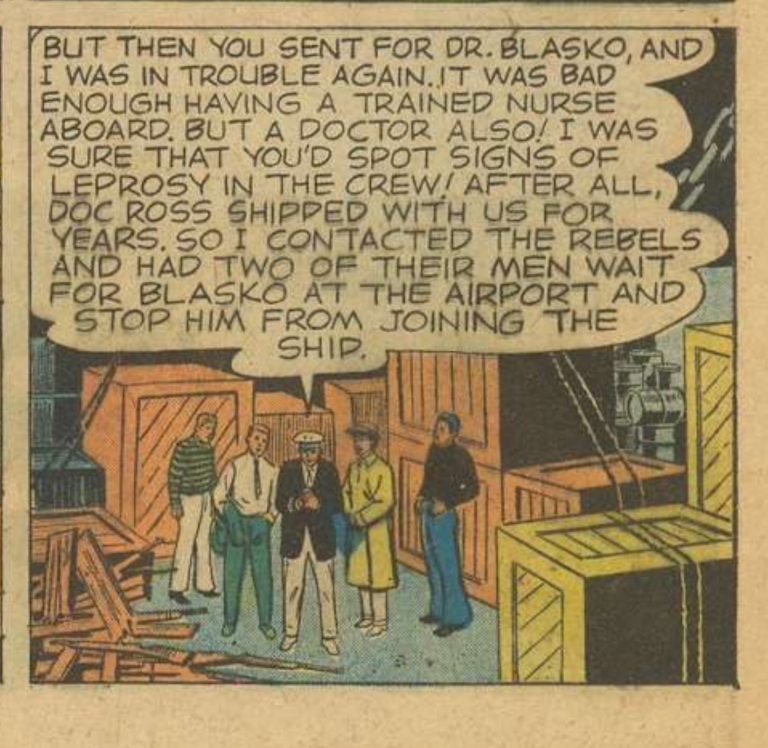

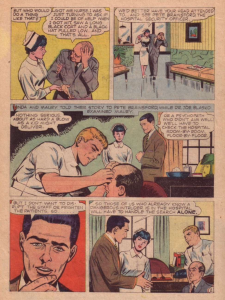

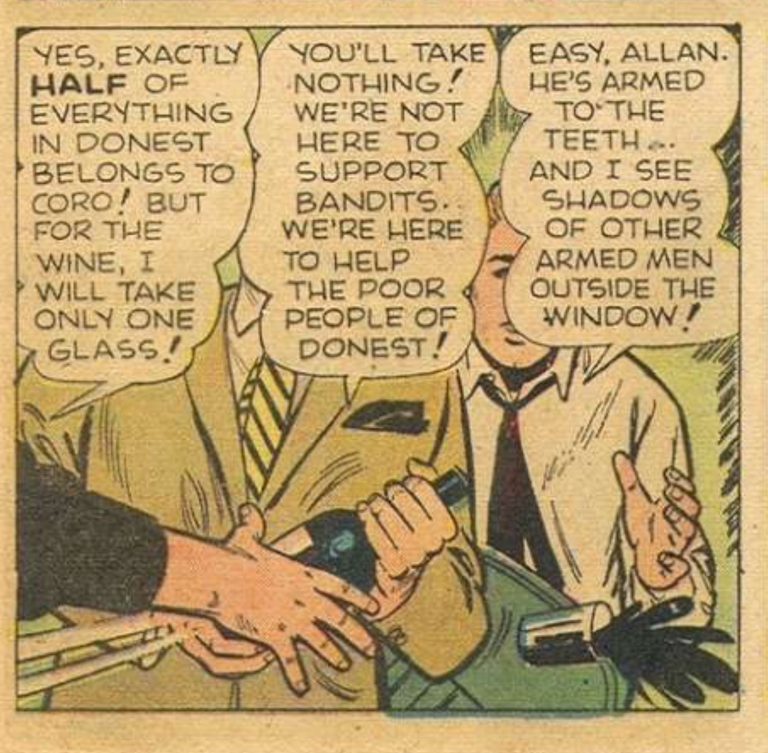

Maybe the best way to see Stanley’s strengths is to look at his weakest ‘62 book, Linda Lark, Registered Nurse (apparently upgraded from “Student Nurse” sometime between ‘62 and ‘61). While his humor comics stretched themselves out in the style modern comics fans call “decompressed,” Linda Lark is brutally cramped. Comics like Thirteen and Kookie gave him the freedom to write rambling stories that took their time to wander around exploring new gags and characters. But soap operas by their nature are heavily plot-driven, and Stanley does his best to squeeze a whole episode’s worth of plot twists into a flimsy twenty-page magazine. While most of Stanley’s work could go on for pages with very few words or none at all, the characters in Linda Lark are often literally dwarfed by their own dialogue.

Other times, there’s so much of it Stanley seems to have no idea where to fit it all and resorts to covering his characters’ faces.

I was going to call this series fast-paced, but that’d be misleading, because they’re extremely light on action. Here, for instance, we have three pages of characters describing and redescribing a potentially exciting scene that happened just offscreen.

I was going to call this series fast-paced, but that’d be misleading, because they’re extremely light on action. Here, for instance, we have three pages of characters describing and redescribing a potentially exciting scene that happened just offscreen.

The backup feature, Tramp Doctor, is even worse. These stories follow a once-promising doctor who descended into alcoholism after failing to keep his wife and baby from dying in childbirth as he attempts to rebuild his career on a small Pacific island where alcohol has been banned. Over at the excellent Stanley Stories site, Number One Stanley Fan Frank M. Young applauds the maturity of the subject matter and suggests it may have been a deeply personal work for Stanley, a recovering alcoholic himself. The execution, though, leaves a little to be desired. If Linda’s adventures felt cramped in the space of twenty pages, you can imagine how breathless the Tramp Doctor’s are in five. Many of these stories cram the entire climax into a single panel.

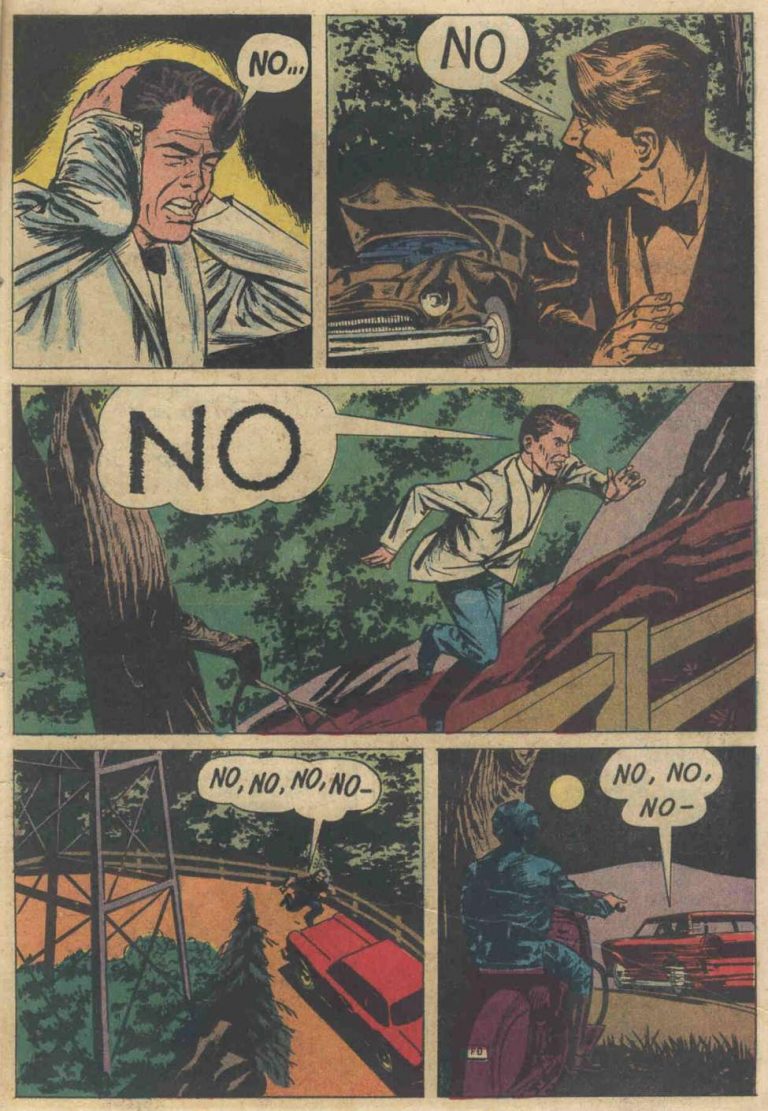

Compare these comics to Tales from the Tomb, where an entire page has no words but the repetition of the syllable “no.”

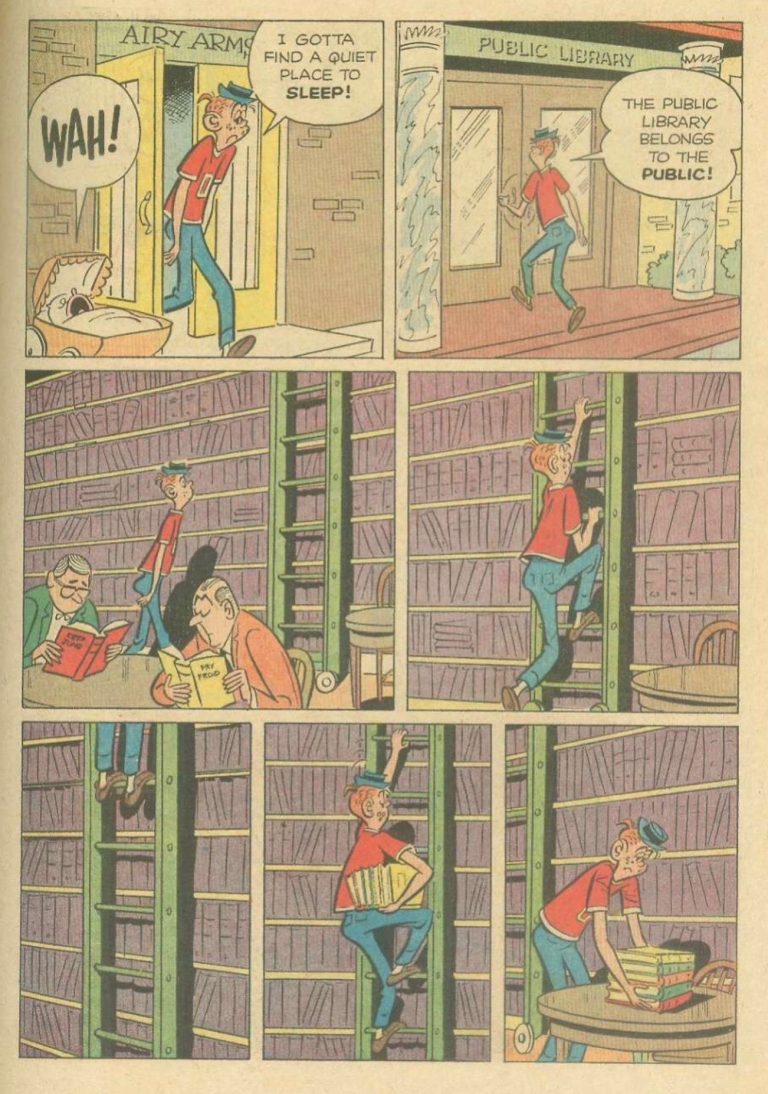

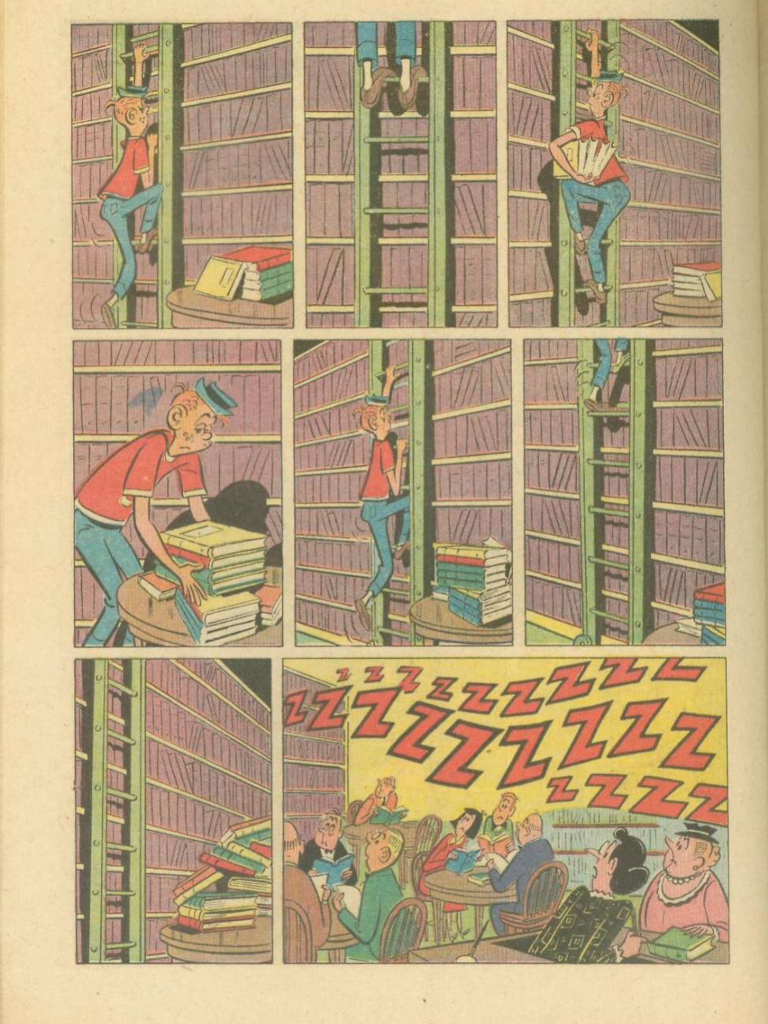

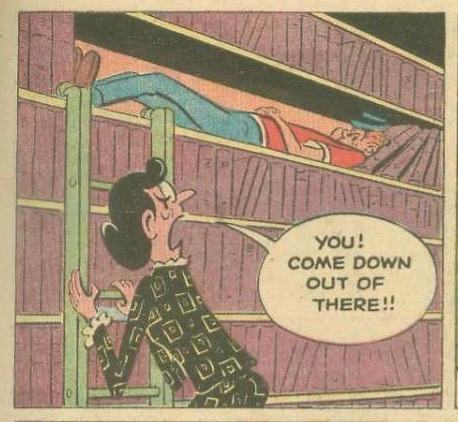

Or Dunc and Loo, where Dunc can take a page and a half to carve out a nest on the library’s bookshelf with no words at all.

It’s apparent that Stanley didn’t enjoy writing Linda Lark much more than I enjoyed reading it. Where he settled into the other series almost immediately, he doesn’t seem to have much idea what to do with Linda. The second issue’s a love-triangle romance, the third’s a detective story, the fourth takes her out of the hospital and onto a ship, and the fifth sends her all the way to the unplacable country of “Strovaka,” where, despite the vaguely Eastern European name, the clothes and language are apparently Italian. It’s not all Stanley’s fault, though: the stiff art by John Tartaliogne drains all the life out of Stanley’s layouts. Even a classic bit of Stanley slapstick falls flat in his hands – compare this scene to Tony Tallarico’s art from Thirteen.

Nellie the Nurse takes the same basic concept, but where Linda plods, Nellie zips along. Linda went along for a year without ever developing much character, but in just a few pages, Nellie comes to life, a contradictory combination of ingenious and ingenuous. Like most of Stanley’s characters, she lives by her own skewed, single-minded logic that leads her very reasonably into some very unreasonable situations with such total conviction that she hardly even notices the chaos she leaves in her wake. Like Little Lulu, Nellie was based on a single-panel cartoon with nothing but a few standard nurse jokes. Stanley took those bare bones and fleshed them out, suggesting in broad strokes a lived-in world within the hospital full of characters who could have kept the series going for years. Of course, the Nellie panel’s idea of nurse-based jokes frequently got raunchy, and even if Stanley didn’t go that far, he went a lot farther than you’d expect in a kid-friendly comic book: one story has Nellie chase a naked patient out of the hospital and through town (hence the overcrowded manhole). We never see her, of course (and, as it turns out, she had never left her clothes behind after all), but this is still more than you’d expect from the era of the draconian Comics Code. Dell was one of the “wholesome” publishers who used the Code to drive their racier competitors out of business, and their reputation allowed them to ignore it. This gave Stanley more freedom than most of his peers, and these comics are much more concerned with sex and desire than most of what was on the racks: even the adults are hormonally horny.

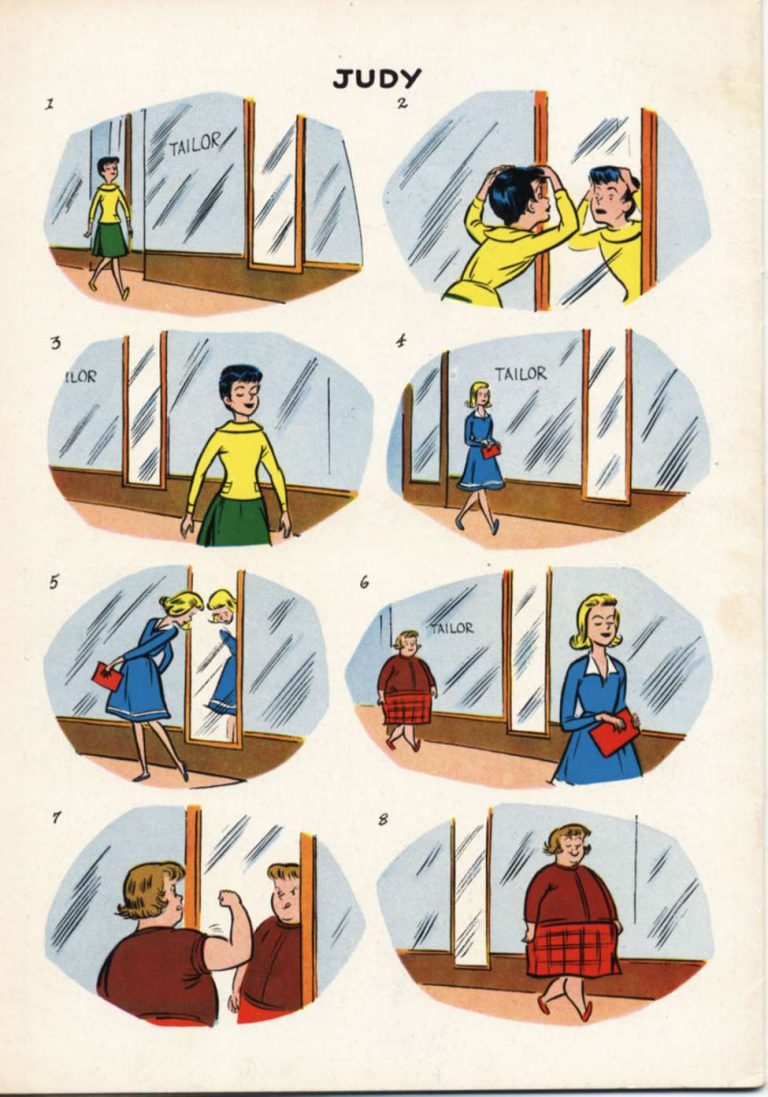

That’s not the only example of hormones raging in Thirteen Going on Eighteen. It makes perfect sense he’d name it after the characters’ age instead of them specifically, because the series is really about the experience of being thirteen, when you feel everything too deeply, when every minor difficulty is more earth-shatteringly important than adults could ever understand. It’s not a coincidence, in other words, that we first see the heroine, Val, bawling into her pillow (“I wasn’t bawling! I was weeping softly!”) When her sister presses her, she says it’s nothing, and she’s more right than she knows — it’s because her mother says she’s too young to wear lipstick. That sets the tone for the series, and if Stanley can find humor in his characters’ high emotions, it’s not because he doesn’t take them seriously. He’s laughing with them, not at them. The same goes for Val’s friend, Judy: she’s a bit heavier (more so every issue), and Stanley finds some comic potential in her appearance and love of food, but there’s also gags that suggest he was an early adopter of what we now call “body positivity.”

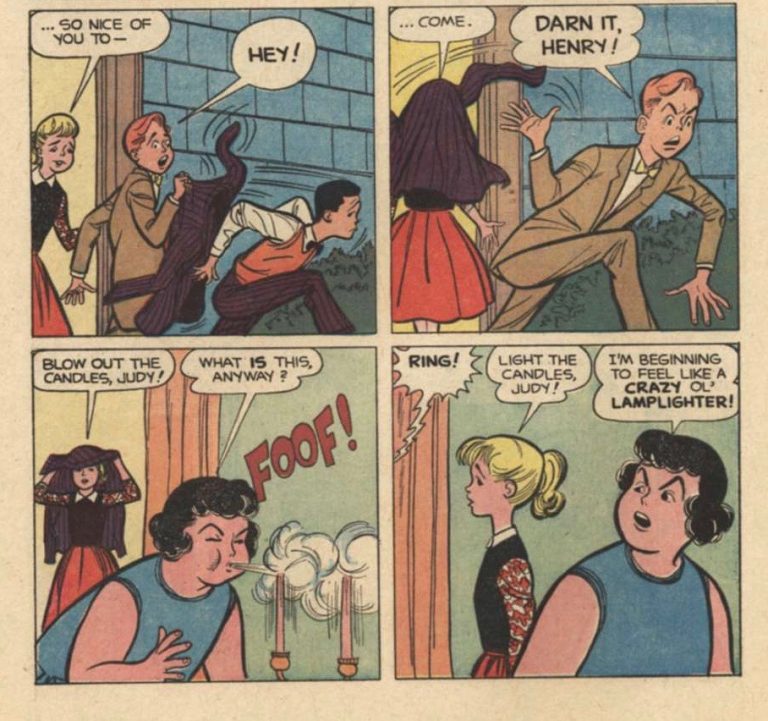

Val’s supposed unattractiveness is the setup for one of the year’s most memorable comic sequences, when Val throws a party and tries to find a date. Her friend Billy manages to drag along the pathologically shy Henry, who runs for the hills whenever the other kids’ backs are turned. This sets up some almost musical comic repetition: “SLAM! — Blow out the candles, Judy — Light the candles, Judy”

and escalation — by the end, she’s blowing the candles all the way off the table.

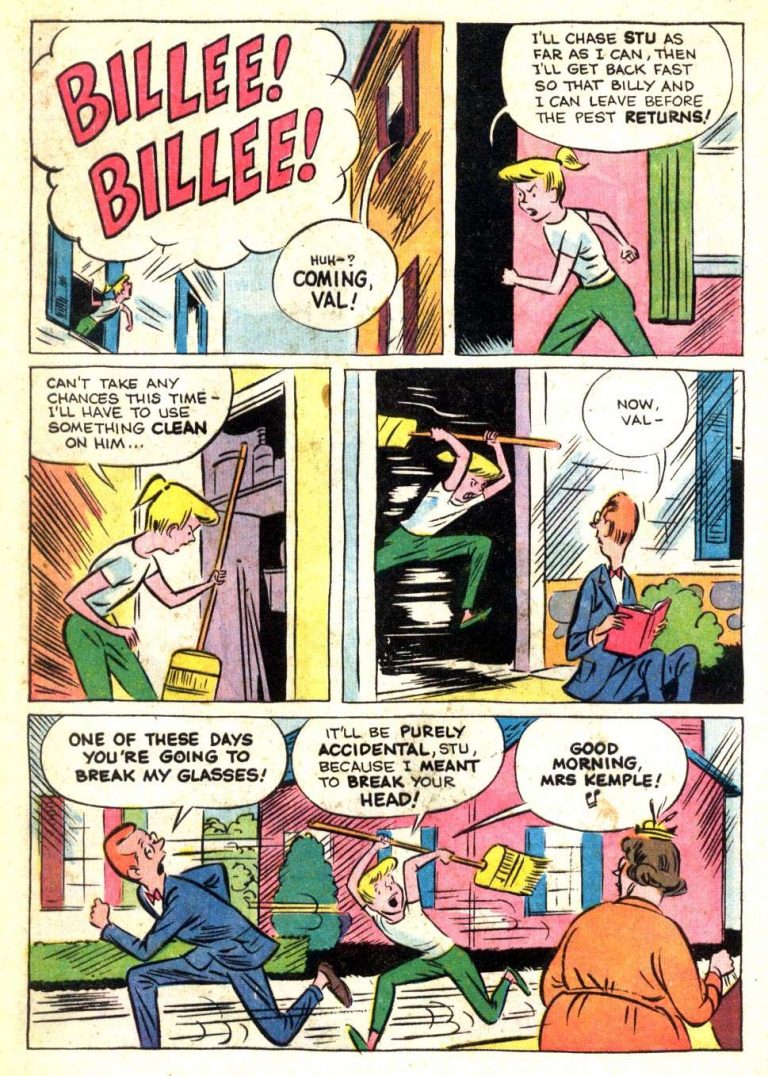

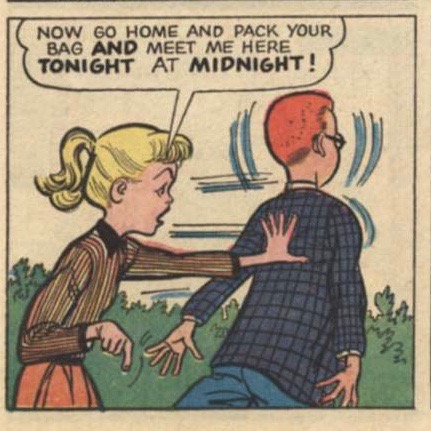

Stanley takes the same approach further over the top in another memorable sequence of Val waiting for her date, Billy, to come over. Unfortunately, another, stalker-y boy, Sticky Stu (sticks like glue) is waiting on the stoop. So this sets up the cycle: call Billy, chase Stu around the block with the broom, and call for Billy again, the word balloon getting bigger and louder each time.

Tweenage emotions are a natural match for Stanley’s slapstick sensibility, giving him license for outsized theatrical gestures.

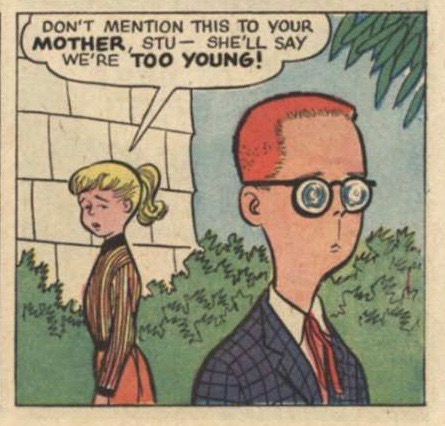

The issues with finishes by Tallarico and Stanley himself each have their strengths. Stanley’s loose, sketchy artwork preserves the raw energy of his “roughs,” but Tallarico’s clean lines are full of retro elegance. And they can liven up the comedy too: just his design for Sticky Stu is good for a laugh without him needing to say or do anything funny:

The series’ back pages also featured the adventures of Judy Junior. It’s unclear who she is – Judy’s childhood past? The child she might have and name after herself in the future? Her and her recurring victim Jimmi Fuzzi inexplicably always referring to each other by their full names doesn’t clear things up any either. But this series, and “Petey” in Dunc and Loo give Stanley a break from his adult and adolescent characters to exercise one of his greatest strengths. Even though he didn’t have children until later in life, he had a genius for writing them, and they were the best outlets for the relentlessly skewed logic he loved writing so much. There’s that deadpan absurdity I mentioned before, as these child characters say the most outlandish things (either because there’s something to gain or they really believe them) with total conviction and unassailable logic.