Despite all of the arguments made for our brave new world of the instant availability of films, the fact is that many significant releases remain unavailable. In particular, independent films by those working outside of the Hollywood system rarely stay in print. With sensibilities often at odds with the mainstream, these kinds of films serve as a kind of litmus test for how film is valued. If the answer leads only to box-office figures, it looks doubtful that the problem will be resolved any time soon.

The film that will be discussed is a particularly curious case of neglect: it received an Oscar nomination for best actress, made a loud and clear feminist statement, and had two formidable performances by male leads. And yet, remains sadly out of print.

Bad Acting: Diary of a Mad Housewife

(dir. Perry 1970)

A powerful idea that feminism expresses is that patriarchy hurts both men and women. While at first, this may seem counterintuitive, the fact is that for men to stay at top of the social order, they must play certain roles. This goes for all men, regardless if they are capable of playing, or want to play these roles. As a further cautionary note, the film suggests there are indeed few options available: mostly limited to either husband/father or gigolo—the masculine equivalents, you might say, of virgin and whore.

What drives Tina Balser crazy is that she is in relationships with two men who are really bad at acting their roles. Her husband, Jonathan, seems perpetually out of his league in playing the social advancement game. Her lover, George Prager, makes such overheated declarations of his sexual independence that we come to suspect that he lacks access to a genuine understanding of himself.

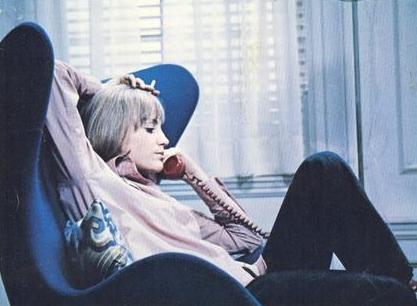

Even before she meets George, Tina wavers between feeling vulnerable and disillusioned. We see her awake in the morning, already looking tired, wrung-out. Jonathan wastes no time in berating her for getting up fifteen minutes late and continues to insult her appearance while they’re in the bedroom together. We watch her go through a typical routine of phone calls, errands, laundry, food preparation, and encounters with repairmen that proceeds at rapid pace, with few pauses. Then she has to deal with Jonathan’s petulant griping after he returns home from a day at the law office. His nightly request for sex sounds absurdly comical: “How about a lil’ ol’ roll in de hay?”, complete with a cornpone accent.

To say that Jonathan drives Tina into the arms of another man is almost an understatement. His tantrums erupt whenever he does not get his way (which, sadly, seem to have worked so far in steering the relationship). George, however, plays a different kind of mind game, a variation on victim blaming: he acts coldly abusive to Tina, while insisting that this is what she really wants. The sex may appear satisfying, but at what cost? George’s being a writer with pronounced bohemian airs may allow him a distance from the stuffy social circle into which Jonathan drags Tina, but his macho attitude reminds us there can be less difference between liberal and conservative male attitudes about sex than might be assumed.

Relationships in this film look about as exciting as the bland omelets served at the social gala that Jonathan and Tina host at their apartment. Tina earlier tries to point out that the high-priced caterer Jonathan has his sights on hiring (and does) is already out of style. Emerging out of the early-70s setting are some sharp jabs at the NYC in-crowd. There are numerous signs of casual rudeness exhibited by their guests; one even makes off with a prized figurine of Jonathan’s.

In these shark-infested social waters George swims with ease. Played masterfully by Frank Langella, his heavy-lidded sensuality has smoldered a bit too long, as if he’s jumped straight from decadence to boredom—and missed most, if not all, of the fun in between. Jonathan, who is not waving, but drowning, also is unhappy, but expresses it differently. In this role, Richard Benjamin speaks every line with a grating edge, his awkward gestures drawing attention to his lack of polish. Jonathan might act like an utter buffoon around Tina because he knows he can get away with it, yet he is unaware that he tends to come across this way to everyone else. A previous scene at an Italian restaurant is quite revealing: Jonathan completely misreads subtle cues and thus has no idea of how the waiter cleverly pokes fun at his pretensions of being a food and wine expert.

But it is Carrie Snodgress, in the role of Tina, who steals the spotlight (earning a well-deserved Oscar nomination for best actress). Snodgress plays Tina with an unnerving sense of calm, while slowly escalating her anger. Throughout, Tina speaks in a choked voice, sounding like a muted trumpet. But the frustration in her eyes warns us that she’s going to blow soon. This moment occurs when she catches Jonathan openly mocking her in front of her children. As soon as she hears her children laughing at her, she lets loose. Of all his offenses, it is this moment when Jonathan finally has gone too far.

George gets his, too. Tina raises the stakes by verbally attacking him, for numerous good reasons, of course. His response, physical brutality, fails to shock her, instead reminding her of the childish outbursts of her husband, making her more angry. She again speaks her thoughts, telling George she suspects him of being gay—although her blunt use of “fag” in this scene would, if the film were watched now, make her less appealing in our eyes.

But the value of what the affair with George teaches her about pleasure and intimacy is fleeting, for her husband’s life has just about fallen apart. In a late-night confession, Jonathan tells her he’s been having an affair, has lost their savings on an ill-advised investment, and is in danger of losing his job.

The scene suddenly shifts to a group therapy session. Tina has just finished speaking: the entire film has been from her perspective. Immediately, a red-faced man (a memorable cameo by Peter Boyle) loudly criticizes her for not having told her husband about her affair. Another woman can’t understand why Tina’s not grateful for having a husband who supports her (although this woman may have missed or misheard some of the more important parts of the story). While Tina remains silent as the debate erupts, the point is clear: Tina, by telling her story, may have won a momentary battle, but the war remains to be fought—and, the film reminds us, it is how the lines are drawn that determines which side the viewer is on.