Spoilers for Selma and Lincoln follow:

There has been so much furor and gnashing of teeth over the way Ava DuVernay’s richly drawn new film Selma depicts President Lyndon Johnson that I am loathe to add anything to the overstated controversy. Nevertheless, I felt obliged to point out what this controversy has to say about the way we talk about politically-inclined historical films, particularly those dealing with race. In light of this morning’s Academy Award nominations, which saw Selma nominated only for Best Picture and Best Original Song, with notable absences in the Best Actor, Best Director, and Best Original Screenplay categories, we must begin to ask why this particular film has been the font of so many righteously indignant thinkpieces and angry op-eds, which, when taken together, seemed to torpedo the film’s Oscar chances.

The key film to discuss in comparison with Selma is Steven Spielberg’s 2012 masterpiece Lincoln.

Set exactly 100 years apart from each other, Selma and Lincoln collectively depict America’s struggle to live up to the promise set by the Founding Fathers: “That all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these rights are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” In Lincoln, the eponymous president (Daniel Day-Lewis), entering his second term in the White House, chooses to accelerate the passage of a new constitutional amendment abolishing slavery, despite the fact that it has a very unlikely chance of being approved by Congress, in order to make sure the slaves are freed before the war’s end, before the former Confederate states have a chance to block its ratification. In Selma, preacher and civil rights leader Martin Luther King (David Oyelowo) chooses to stage a massive demonstration for voting rights in the heart of rural Alabama, despite the fact that such a protest would be extremely difficult and dangerous, in order to re-focus national attention on the matter of voting rights for black Americans.

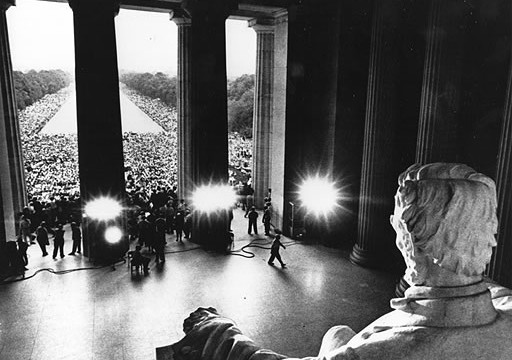

The two films have many similarities in tone — very dialogue driven, expecting the audience to keep up with historical references they might not be familiar with — and even structure. Both begin with their iconic lead characters feeling the pressure of their actions not living up the lofty heights of their rhetoric. In Spielberg’s film, Abraham Lincoln finds himself guilted by a brief encounter with a black Union solider played, oddly enough, by David Oyelowo, who recites the Gettysburg Address after bringing up the fact that he cannot legally vote and is paid less than his white counterparts. In Selma, Martin Luther King privately rehearses his acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize, but cannot finish without mentioning how wrong it feels to accept a prize amongst the international high society while black people in the south are murdered every day. Both films avoid the typical birth-to-death biopic structure in favor of focusing on only a few months. Both end with the hero delivering a speech on the steps of a capitol building to an enormous crowd, having accomplished the goal for which they have striven so hard. Even in their differences the two films show similar artistic desires. For Lincoln, Spielberg and cinematographer Janusz Kaminski filmed the scenes in a chiaroscuro method, using light so that it would tend to be cast on Day-Lewis’ Lincoln, drawing the audience’s attention to the President in nearly every scene where he’s present. In a more unusual, but not entirely unrelated move, DuVernay and D.P. Bradford Young instead choose to build the images of Selma around darkness rather than light — often, King is seen in shadow or silhouette, a curious yet ultimately effective move; it obscures the lead character of the film, yet manages to create an “black is beautiful” message, crafting the film around the wonder of darkness rather than light.

The two films primarily differ in where exactly the political story ends up going. Lincoln takes place almost entirely in Washington: in the White House, on the floor of the House of Representatives, in the homes of the power brokers and the backrooms of party headquarters. Its central players are presidents, cabinet secretaries, diplomats, generals, and congressmen. It is politics as it understood at the top of the pyramid. Selma, on the other hand, is of the streets, in small town churches, in diners, in cramped rural homes. It is the story of the people on the ground floor of social change: the church deacons, the nurses, and the pensioners. It is politics as enacted by everyday people.

Lincoln g0t some faint criticism at the time of its release; a small number of commentators felt the film gave short shrift to the black abolitionists who spent decades attempting to abolishing slavery. To these critics, Lincoln focused on a privileged and powerful white man at the expense of the black men and women whose struggles no doubt played an enormous and essential role in ending bondage in the American states. But such criticisms were specious. Does Lincoln focus on black abolitionists? No, but it also doesn’t really focus on white union soldiers, black union soldiers, British abolitionists in the 1820s, Vice President Andrew Johnson, or any of the other various actors and players relating to the period and the subject matter — because Spielberg and company were telling a story, a needed to focus on a particular aspect of that larger historical issue; in this case, the nuts and bolts of getting legislation passed against all the odds. The prior work of the abolitionist movement is commented upon in the film, briefly, but not delved into. But it didn’t need to be for this particular story.

Selma is the flip side to Lincoln, where the movement of “the people” — on the streets, being beaten by cops and denied their right to vote — is the focus of the film, at the expense of the high offices of power. The main conflict of the movie is between King and President Johnson, who is sympathetic to King, but is unwilling to focus his administration on voting rights for the time. LBJ continuously tells MLK “It’s not time. We need to wait,” but in a wonderful scene late in the film, King puts things into perspective for Johnson, reminding him that he’s just a preacher with a church in Atlanta, while Johnson is the President of the United States. At the end of the film, sufficiently convinced by King’s activity, and the will of the nation, Johnson announces his advancement of a new Voting Rights Act (the culmination of something that began shortly before Lincoln’s assassination a century earlier). If Lincoln gives somewhat short shrift, historiographically speaking, to the deeds of the abolitionists and antislavery activists, Selma can be said to be a little simplistic in its portrait of high-level Washington politics. Johnson announces on live TV his intent to pass a Voting Rights Act, and the film basically treats this as a done deal. A Lincoln style approach would have to show the cajoling, the arm-twisting, the political maneuvers and sacrifices that Johnson would need to complete in order to get the bill passed, but for Selma, that is unnecessary. Each of these two films is the story that they tell, and that’s what they need to be.

Taken together, they show the two faces of politics: the on-the-street demonstrations that must be done, and the legislative advancement that must follow. Yet only one of these films — of comparable cinematic quality, I would argue — has seen its Oscar chances seriously hindered by allegations of historical unfairness. And that movie is the bedeviled, beleaguered Selma, which has deserved maybe one-twentieth of the controversy it is has drudged up, and much more praise for doing what it does well than it has so far received.

The reason for this goes back to the fundamental differences in what part of American life these films choose to show. Lincoln focuses on a white man in a position of authority, “clothed in immense powers,” in the words of Honest Abe himself. Selma focuses, mainly, on black men and women who cannot even exercise their right to vote. And the mostly white detractors of Selma seem offended entirely by the idea that the reputation of a powerful white man might be somewhat hurt, or more accurately downplayed in favor of the actions of those black individuals.

The controversy on Lincoln flew by quickly. It was worth discussing, but there really wasn’t much discussion to be had. And after a few months of release, the film saw itself rewarded with twelve Academy Award nominations. Selma, on the other hand, has had the conversation around it focused almost entirely on how it does or does not depict a powerful white man, something that is worth discussing, but not nearly to the overindulgent extent to which it has been. It’s bitterly revealing about American culture that Selma apparently started out as a script by Paul Webb, a white man, that focused primarily on Johnson before being re-written by director Ava DuVernay (a black woman), only to find itself primarily discussed about in how it depicts a white man. Apparently, you are allowed to downplay or streamline the struggles and efforts of black abolitionists, but for the love of God, do not depict a powerful white man in a not-always-flattering light.

In the end, the films Selma and Lincoln can be taken together as a powerful diptych about what freedom and justice mean in an often compromised American landscape, and both are fabulously made films of rare depth and intelligence. Yet the controversy that ravenously affixed itself to one at not the other might tell us even more about how compromised and unjust our American landscape can be.