You wanted to do exceedingly big things, but you’ll do small ones instead. That’s good.

– Čapek, Krakatit, ch. LIV.

On May 25, 1917, a large fire broke out at the Škoda factory in Bolevec, within the Czech city of Plzeň. The factory was producing munitions for the Austro-Hungarian army, and when those munitions caught fire, it led to a series of explosions that killed hundreds of workers, of which dozens were children.

Some 25 miles away, an aspiring young writer named Karel Čapek watched the explosions from a window at the Chyše chateau, where he was working as a private tutor. A few years later, Čapek would publish his second novel, Krakatit, an old-school SF yarn about a chemical reaction that releases atomic energy in the form of massive explosions. The invention upends the entire global order.

And a quarter-century after that, the father of Czech-language cinema, Otakar Vávra, would adapt Čapek’s novel into a streamlined SF noir. The differences are stark, but so are the contexts: Čapek had extrapolated a new world from the smoke of a munitions factory; Vávra directed his adaptation three years after Hiroshima created that world.

In short, there’s a lot to unpack here both about the movie and about its transition from reality to fiction to reality and back again. Let’s set the stage with a quick look at the trailer (not the original, but a slick modern trailer produced by the CZ National Film Archive):

The Novel

If English speakers know Karel Čapek, it’s almost certainly because of his first play, R.U.R., which introduced the word “robot” to the world (a coinage from his brother Josef. Futurama paid them homage with a planet). The play is not particularly good, especially in light of his mature work, but it establishes certain themes that would recur throughout Čapek’s career: an interest in the fantastical, an enormous breadth of ideas explored (political, social, economic, philosophical, etc.), and an apocalyptic anxiety that he refused, as a matter of moral principle, to assuage with happy endings. The “Robot Play” ends with our artificial creations not only rebelling but winning, wiping the human race from the map. His last completed novel, the magnificent War with the Newts, ends with the last remnants of humanity clinging to mountaintops as an army of intelligent salamanders flood the planet in retaliation while the narrator openly mocks the possibility of any Wellsian deus ex machina. In both cases, though the instruments of our destruction are independent beings, we alone are responsible for sowing those seeds.

This all sounds dour enough, but Čapek’s work tends toward a lightness that would seem incongruous if he weren’t so damned good at it. He is a consistently charming, amiable writer. He wrote plays and articles, gardening guides and adorable books about his pets, a set of detective stories that can compete with any of the canon, a series of historical “rewrites” that would make Borges proud, a trio of “noetic” novels dealing with the epistemological problems of knowledge of self and others, and interviews with Tomáš Masaryk, the first president of Czechoslovakia. He was responsible for popularizing American pragmatism (the Jamesian philosophy, not the modern platitude) and became one of the first and most vocal opponents abroad of Adolf Hitler’s rise to power. His reputation in the Czech Republic might even be too hagiographic sometimes, but much of that reputation is well-earned.

Čapek’s consistent skepticism might be viewed as a product of the larger context here: he was writing during Czechoslovakia’s first experiment with independence after centuries under Austrian rule, and after The War to End All Wars had left millions of bodies rotting in trenches, no few of which were his countrymen’s. Though starting fresh, the newborn nation also faced internal threats of ethnic, religious, and other identitarian factioning, from the differences in language between the former colonizers (German) and the “native” speakers to the replacement of Catholic (Austrian) monuments with Protestant (Czech/Slovak) ones and the place of ethnic minorities who were neither the colonizers nor the new majority (Jews, Romani), from the rush of ruinous capitalism pouring in from the West to the no less ruinous Soviet expansion in the East — what kind of country Czechoslovakia would be, small and “insignificant” as it was, is inscribed throughout Čapek’s work. Reflecting on the devastation of postwar Central Europe, he has an innate suspicion of “-isms”, of totalizing philosophies that absorb all of life’s phenomena into rigid and exclusive solutions, philosophies that do not admit the possibility of a healthy pluralism. In his first novel, Factory of the Absolute, various forms of fanaticism are amplified by a mysterious ether created as a byproduct of atomic annihilation, and it matters little whether the fanatics are religious leaders, businessmen, politicians, or irritable neighbors. In their quest for their own absolutes, they drive us into destruction.

Krakatit continues with these concerns: it’s a novel about the inventor of an explosive chemical that stealthily becomes a novel about a whole host of other issues threatening the stability and persistence of the nation, the continent, and the human race. Čapek was not the first novelist to imagine a world-ending atomic weapon — that honor goes to H.G. Wells — but he traded Wells’ lugubrious utopianism for a breezy pessimism. Krakatit is more romantic than Čapek’s other works, one of the few that puts a love story at the center, but like The Absolute before it, it eventually finds itself cornered with a scenario in which happy endings seem impossible. The inventor Prokop has had his formula stolen by a neighbor, the chemical is spreading around the world, various forces are vying for control of the detonator, and Prokop himself is seduced by the power and charm (and sometimes the actual sex) of the would-be rulers of the world. By this point the story has ascended past the political and sociological into the metaphysical, with an honest-to-god tempter named Daimon and a kindly old man who may in fact be God. Prokop, like Icarus, has flown too close to the sun, but Čapek wonders if we are doomed to continue doing so, no matter how often we get burned. The explosive krakatit is just one of the many ways we risk destroying ourselves, but we don’t lack for others.

In the end, Čapek has little to comfort us outside of a platitude — we all want to do great things, but it’s okay to think small sometimes, too — but he has no real “solution” to the serious problems that unfold in the story. This refusal to “solve” his paradoxes is what keeps his work from sliding too far into didacticism, frustrating as it may be. The terror often underpinning his works is that these problems may not be solvable after all.

The Film

Few filmmakers in any language have a career as long and expansive as Otakar Vávra, who made his first features in the 1930s and his last in the 2000s (he died in 2011 at the age of one hundred). Beginning as an experimental filmmaker, he eventually settled into kitchen-sink social realism and medieval historical dramas, all safe subjects in the series of regimes (Nazi, Soviet) under which he found himself working. His ability to work consistently under these political changes has been a source of no little criticism, a director who kept his head low and met the demands of the authorities while his fellow artists fought back, went to prison, and/or fled the country. What is unequivocal about his career, however, is the impact he made as a pedagogue: a co-founder of the film department at Prague’s Academy of Performing Arts, he was a beloved teacher and mentor to an entire generation of filmmakers, including Miloš Forman, Věra Chytilová, and Jiří Menzel.

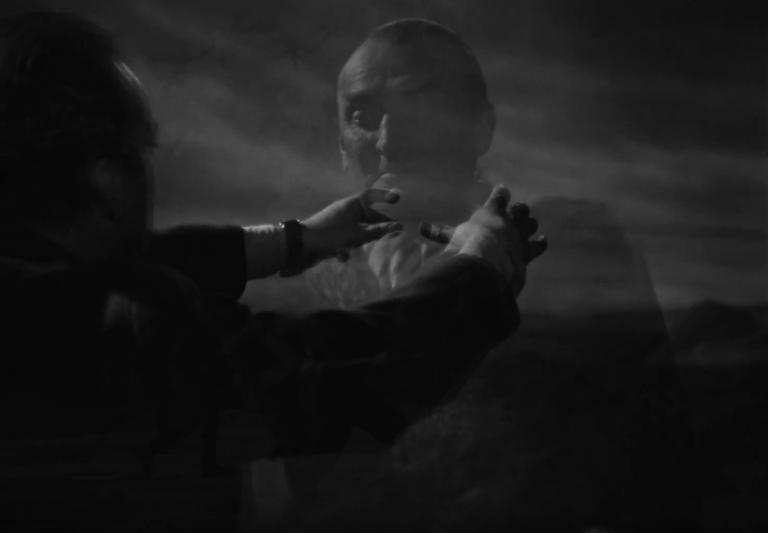

The ghost of Hiroshima looms large over Vávra’s Krakatit. Eschewing Čapek’s more expansive look at the benefits and costs of ambition and the way it affects the delicate balances of social and political calculations, Vávra opts for a more direct broadside against the nuclear age, the threat to the future of the species that the atomic bomb has wrought. The actual explosive krakatit is, Čapek assures us, only a synecdoche of the many forms of self-destruction we find ourselves rushing towards; Vávra, for whom a world-ending bomb is no longer an abstract hypothesis, focuses more directly on the instrument of death itself. Vávra compensates somewhat for the narrowed focus by expanding a brief element from Čapek’s novel — Prokop’s delirium after a near-death experience with krakatit — and turning it into an aesthetic. The film itself is delirious, borrowing heavily from German Expressionism and its American noir iterations. Where Čapek eventually sends his novel into the metaphysical/allegorical realm, Vávra compensates by giving us straight-up nightmares. Look at how Vávra handles the reveal that the seductive aristocrat who loves Prokop only wants him for his formula is not what she seems:

Simple effects, well deployed: throughout the film, Vávra uses lighting, rear projections, dissolves, canted angles, and clever editing to place us inside Prokop’s deteriorating mind. If nothing else, the movie is often delicious to look at, a burst of visual inventiveness that is, unfortunately, saddled to a somewhat melodramatic but stagnant plot.

Still, a lot of the moments stick. Take the climax, when the book’s awkwardly named Daimon becomes the even more awkwardly named D’Hémon, a tempter who introduces Prokop to the full potential of his power as the man controlling the detonator. Some 40 years before Ozymandias, D’Hémon delivers his eeeevil monologue with a helluva capper: the deed has already been done. The explosions have already begun, and various capital cities are dust. There is nothing Prokop can do to save the dead. The only choice that remains is one of pure power: he who holds the keys rules the world. Like Satan’s third temptation of Christ in the desert, D’Hémon offers Prokop mastery over all the kingdoms of man. Prokop fights back only to have D’Hémon dematerialize in his hands. Where does the delirium end and the real nightmare begin?

It’s a mad film full of mad people, and the final act’s kindly old carriage-driver/God offers only the comfort of a shoulder and a gentle voice (though the waking nightmare continues even here, with the fog and rear projection creating a unreal sense that the only respite available to us is not of this world.)

Čapek’s pessimism already seemed prescient when the novel was published in the early 1920s. The author would die on the eve of Nazi invasion, and his brother perished in a concentration camp. When Vávra turned to the text, the immediacy of Hiroshima and Nagasaki necessitated a different kind of pessimism. As for us, we may have made it out of the Cold War intact, but the bombs are still out there, and human ambition is still leading us along the edges of one precipice or another. However desperately we may need solutions, sometimes it’s enough that our art reflect that predicament honestly.

- Like the other major classic of Czech-language science fiction (the brilliant Ikarie-XB1), Vávra’s film is extremely difficult to get, and doubly difficult to get with English-language subtitles. Amazon shows a PAL-encoded version with English subtitles, but I’m skeptical. (I was fortunate to see the movie years ago in the Czech Republic. No such luck since.)

- You’re probably thinking “Can I get this, but in opera form?” Oh, you most certainly can.

- An early and somewhat uneven novel, Krakatit is not Čapek’s strongest work, but I cannot recommend his late War with the Newts highly enough. As ridiculous as the concept sounds, it’s a thrilling burst of imagination with total control over tone and content, a Modernist masterpiece that also happens to involve world-ending salamander warfare.

- As for Vávra, the best place to start is probably his 1970 film with the most metal name imaginable, Witchhammer, a drama/thriller about a fanatical witch hunter who, after torturing his victims into confessions, finds himself on trail for the same crimes. It’s a far cry from the early experimental work that propelled him to fame, but you can see the craft from someone who knows how to use his medium.