“It was a bad sign when a man like Handy started owning things and started thinking he could afford friendships. Possessions tie a man down and friendships blind him. Parker owned nothing, the men he knew were just that, the men he knew.” — Richard Stark, The Outfit

In 1973, John Flynn adapted The Outfit into what’s probably the best Richard Stark adaptation on the screen. But while it has fine performances and a great seedy milieu, it doesn’t dig into the coldness at the heart of the book and the Parker series in general — what it means to live on your own, beholden to no one, and how a friend is just someone who hasn’t betrayed you yet. But two other movies from 1973 did.

A few years after Charley Varrick came out, Irish blues guitarist Rory Gallagher wrote an asskicking song inspired by him, mythologizing a outlaw who takes on the Mob because fuck those guys. Charley does — or doesn’t do — things his way, on his own. He used to be a stunt pilot and still owns a plane, which he used for cropdusting until the big combines forced him out. His business slogan, which Gallagher stole for the song’s title, was “Last of the Independents.”

But he wasn’t always that way. Charley’s wife Nadine has been with him for a while. She’s the getaway driver for the robbery of a tiny New Mexico bank Charley masterminds at the start of the movie. And when a couple cops realize something is up she guns them both down — killing one and precipitating another fatal shootout in the bank — and is fatally shot herself. She still manages to drive the surviving heisters away before dying in Charley’s arms.

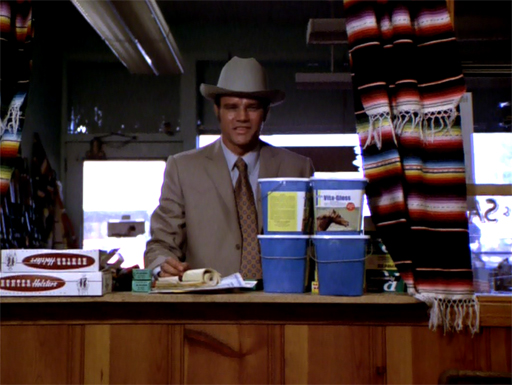

This lengthy sequence sets the movie’s strange, dispassionate tone. Director Don Siegel keeps the movie not sparse, but uncluttered — nothing distracts from what we are seeing, as opposed to how we are seeing it. (Point Blank this is not). The movie opens with idyllic images of ranchers starting their day and townsfolk going about their business, before the title character blows everything to hell with his heist. There’s no hokey hick irony. Siegel is suggesting that there is a place where people can peacefully exist together, and spends the rest of the movie showing what also exists underneath that — a pawnbroker is a underworld envoy, a photographer makes fake IDs, a restaurant conceals a gambling room, another ranch is a whorehouse. After Nadine dies, Charley kisses his her goodbye. Then he blows up her body and the getaway car. Less evidence, you see. Leave no trace.

No bank robbers here.

The entirety of New Mexico’s law enforcement is hunting Charley and Harman, his remaining accomplice, and so is the Mob — the bank they knocked over was secretly a storage point for their casino skim and they wound up with nearly a million dollars in dirty money. But Charley never acts like he’s under pressure. He has a goal — keep the money and live — and goes about achieving it with the same emotionlessness he had during the heist, during the getaway, during his wife’s death. Maybe he relied on her once, but now he relies only on himself as he tries to get a fake passport and navigates an underworld all too eager to sell him out to the Mob and the man they’ve set after him. Matthau complained to director Don Siegel about the character’s vagueness, but on screen he lets that saggy, craggy face and its watchful eyes put a lid on any questions about who he is while letting his actions eventually speak for themselves.

Joe Don Baker, aka Molly, also speaks through his actions. He’s an ancestor of Anton Chigurh, the guy you hire to get something back but who has his own agenda. Molly is casually brutal and cruel, but he’s also extremely eager to pin the blame for the heist on Mob middle manager Boyle, who set up the original arrangement with the bank. There’s no reason for him to want this (and Boyle is very much innocent), but he does. Maybe it’s his own way of staying independent. But he still needs the Mob to wind him up and set him loose, to make him more than a very bad man who likes to hurt people. At one point he mocks Varrick’s motto — “It has a ring of finality” — but he is part of a machine, a network of other people with demands and motives and betrayals of their own, no matter how much he pretends otherwise.

“I didn’t travel 600 miles for the amusement of morons.”

Molly spends the movie tracking Varrick and the money, at one point gladly but professionally beating Harman first for information and then just to kill him off. Varrick, hiding nearby, watches this and does nothing. Yet. Boyle, for his part, knows Molly suspects him and is more than willing to put the blame on someone else. In a long conversation with the banker who helped set up storage for the mob money, who’s been losing his mind since the heist, Vernon uses all of his insistent unction and authority to lay out just what happens to a person who fucks the Mob over. A few years later, he would openly tell John Belushi that fat, drunk and stupid is no way to go through life — here he makes it clear to the manager that being tied to these people, being alive with them, is no way to go through life. The manager takes his meaning, and knows Boyle’s suggestion of running away is facetious. He’s too connected to the community, he can’t leave his life behind like that. But he can end it.

Charley, though, can move on. He sets up a meet with Boyle to return the money and lets the location slip to Molly, who stakes out the drop point. When Varrick arrives, he embraces a befuddled Boyle and acts like they’re partners — all the impetus Molly needs to run Boyle down (now with a look of glee on his face, the organization man unleashed) and beat up Varrick, who tells Molly the money is in a nearby car’s trunk. It’s not. What is in there is Harman’s corpse in Varrick’s clothes and a bomb. The latter explodes, killing Molly and making a plausible substitute Varrick out of Harman in the process. Game, set and match to Charley Varrick.

Who is now officially dead. The last thing Matthau does is take off his flight jersey with that “Last of the Independents” motto and kiss it goodbye, just like he did his dead wife. Then he throws it in the fire. Charley Varrick won, Charley Varrick is gone. He’s never said where he’s going to go, who he will be now. He’s truly independent now, tied to nothing and no one — not even a self he will share with us. No other people allowed.

But money is OK.

***

The irony of The Friends Of Eddie Coyle’s title is too blunt to be cute. Eddie has no friends and probably never did. He lives in a cramped house in Quincy, a town south of Boston that’s more working class than the burbs where mobsters he’s helped arm rob banks, and far less fancy than the tony neighborhoods where the bank’s managers live (one of the movie’s many true touches about life in Boston is how much life takes place outside of it). He’s a middleman who moves guns and tries to make himself useful to the Boston mob, meeting contacts at shitty buffets and in grocery store parking lots. He’s always hustling someone, making his case. And he has a hard case to make.

Eddie got caught moving some guns on his own and is facing serious prison time. So he’s desperately dealing with FBI agent Dave Foley while continuing to buy guns for Jimmy Scalise, leader of the bank robbers, from a young guy named Jackie Brown. And he goes to the tavern to bitch to his bartender, Dillon, a felon and hit man who is an informant for Foley as well. The story comes from George V. Higgins’ novel, which inspired Elmore Leonard to switch from cowboys to lowlifes and pretty much changed crime fiction permanently. The book is 80 percent dialogue, it moves in the conversations among these and other characters as they bullshit and manipulate and cajole, and the movie is smart enough to keep as much of that dynamic as possible. Most importantly, it keeps the diffuse yet suffocating structure.

Charley Varrick makes moves we don’t understand until the end, but his actions hover over the film even when it follows his enemies, whose motivations are clear. Eddie disappears for large chunks of the movie while we follow other characters and connections only become apparent over time and obliquely at that, but every move made narrows Eddie’s options. And while Matthau’s Charley is weathered but inscrutable, Robert Mitchum’s Eddie is beaten down and easy to read in his neediness and limitations. He wants to live, just as much as Charley does, but for what? To keep scraping away at a life where every interaction is a struggle to get ahead, where everyone he talks with is either using him or being used?

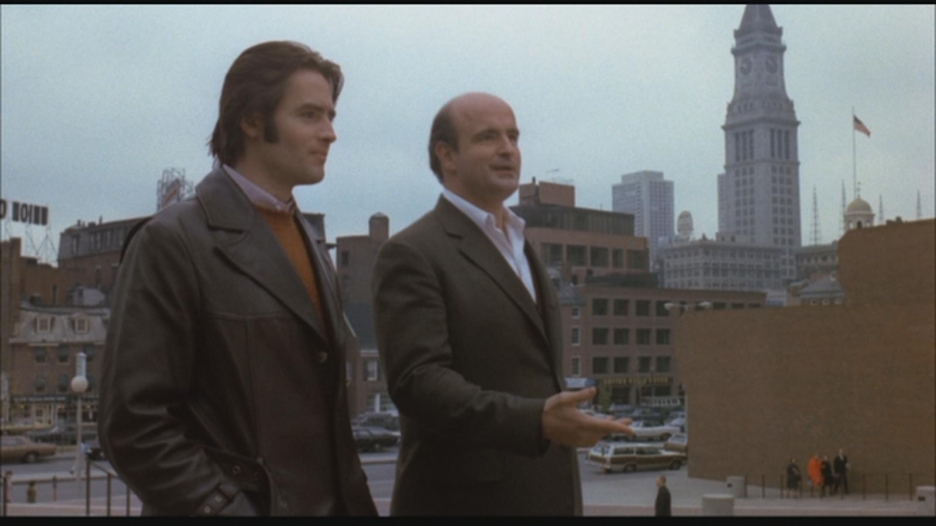

Men at work

Director Peter Yates surehandedly lets this unfold and underplays everything, with the help of Victor J. Kemper behind the camera — the misery of Massachusetts in fall and winter is here, greys and browns and overcoats against the wind (there is more sunlight in the first five minutes of Charley Varrick than the entirety of this movie). Characters circumnavigate the Brutalist slab of City Hall and the brick wasteland of its Plaza, which was only five years old when the movie was made and already feels eternal in its oppression (and still looks like that now). Yates himself was only five years out from directing the car chase that defined the conceit in Bullitt, here the lone car chase takes place in a parking lot and ends after a minute. The chasee is caught, of course.

That would be young Jackie Brown, nabbed with a bunch of machine guns destined for some hippie revolutionaries in his trunk. He’s nabbed because of Eddie, who finks on Jackie because Foley implied giving up another crook would shorten his own hard time. It’s not enough, of course. Foley, who has his own boss to answer to, isn’t about to give up on squeezing a rat so easy when he can keep squealing. He needs more, he tells Eddie. So Eddie decides to go full snitch and rat out Scalise, a connected guy. Only one problem — Dillon snitches to Foley first, and Foley sweeps up Scalise easy as you please, before Eddie can even make the offer. But Eddie’s eagerness to deal — now out in the open after Jackie’s arrest — gives Dillon the perfect fall guy to throw out for the mobsters who are suspecting that he is a snitch.

So he talks to the man who works for the man, gets $5,000 for the hit after some tough words and pushback against unprofessional bullshit. And then Dillon and Eddie and Dillon’s “nephew” go to a Bruins game. “Numbah fouah, Bobby Oaah!” Eddie slurs, drunk on cheap beer like everyone else at the Garden. He’s packed into a car, where he passes out. And on Morrissey Boulevard, that long stretch of road down the city’s coast into Dorchester, Dillon shoots him in the head and leaves his body in the all-night Bowlarama parking lot.

The death is a blip on Foley’s radar and he obliquely asks Dillon about it, and Dillon just as obliquely shies away from saying anything. There is an understanding here. Foley got a bust, Dillon got away with murder, they’ll both get to keep on doing what they do. Like the schlubs at the bank who never say a word during the hold-ups. Eddie Coyle punched out and no one cares, they have clocks of their own to punch.

Morning, Ralph. Morning, Sam.

***

When Charley Varrick is robbing that bank to start the movie, the manager hesitates at opening up the safe. Matthau looks at him: “You want to die for other people’s money?” The idea of fighting for something that isn’t yours is anathema to him. Of course, the irony is that the manager will wind up dying for this money. But in the moment, he opens up the safe.

The way Scalise and his crew rob their banks is smart and professional. They roust the bank manager at his home and take him to the bank, leaving a goon with a gun on his family. The manager explains what’s happening, including the threat to his wife and kids, as the robbers ransack the place. It works like a charm the first time. But the second time, an underling decides to get cute. He slowly moves his hand to the silent alarm button under the desk. Presses it. Moves his hand back up. And is seen, of course. An angry heister shoots him dead and the crew rushes out, now with a murder hanging over their heads instead of just armed robbery.

Shooting the guy is a stupid move — if nothing else, the button has been pushed, the worst has happened already — and it’s also, you know, murder. But watching it, I was infuriated far more with that dipshit for pushing the button. Knowing that someone else’s family is at stake, that his co-workers are in jeopardy, that his own idiot life could be forfeit. And for what? Other people’s money. What an asshole. He deserves what he got.

“The only one fucking Eddie Coyle is Eddie Coyle,” Foley tells Eddie as Eddie is looking for mercy, blaming others for his predicament. In a movie full of half-truths and elisions and betrayals, it’s the greatest and bleakest lie of them all. You did this to yourself, whatever comes down is on your head. It’s what I feel for that middle manager, the Eddie Coyle of the bank, who tries to be smart and is killed for his stupidity. But what about the people robbing the bank in the first place? Eddie started down his fatal path on his own, but what about Foley, making promises he never intends to keep and drawing Eddie further down the road to his death, or Dillon, passing his own betrayals off on Eddie and then taking money to kill him for Dillon’s own sins? Everyone is fucking everyone, all the time.

Eddie Coyle’s Boston is a place where everyone knows everyone else, there are no coincidences, no independents throwing things out of whack. And if someone does get a bright idea to switch things up, to play a different game, they’re swatted down. And no one is satisfied, not the bankers in their mansions or the gun runners hustling M-16s. They’re all working for themselves but tied to each other, unable to escape. It’s a despairing city on a weary hill. Eddie Coyle is blinded to this because he believes in his so-called friends and dies because of it, but it’s not like their lives are much better.

Charley Varrick gets away from all that. He gets his life and his money, and he even gets a song. “I’ll play it my own way / I’m the Last of the Independents / Well, I play by my own rules,” Cochran sings. If the movie is too aloof to be romantic, it allows him the outlaw mystique of a D.B. Cooper. He doesn’t get an ending, but a disappearance from a world out to get him and the satisfaction of doing it on his own terms. Charley Varrick escapes other people, Eddie Coyle is done in by them. But you can never really get away from everyone the way Charley does, right? And if you can’t, you’re just marking time until you find out who your friends are.