One might argue that the sustained popularity of the heist film lies with the struggle between rationality and morality. The first two acts usually deal with the planning and execution of an elaborately plotted robbery, combining the elements of strategy in the former and tactics in the latter. The final act, however, shows how the characters’ personalities and motives undermine the operation’s instrumentalist imperatives. The formula allows for a maximum degree of structural innovation to flourish within a traditional set of narrative expectations.

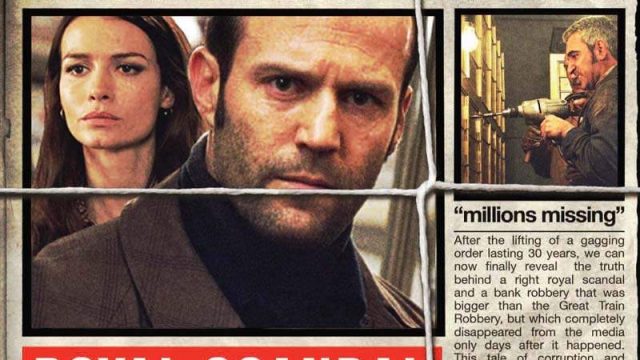

Take, for instance, 2008’s The Bank Job. Continuing a trend started with Guy Ritchies’ Lock, Stock, and Two Smoking Barrels, it depicts a group of cockney lads concocting and executing a robbery with borderline competence, only to unleash the full wrath of better organized criminals and corrupt law enforcement officials, with darkly comical results. This picture introduces a dizzying array of historical references to the scandals chronicled in the 1970s London scandal sheets. In this genre entry, the heist film becomes a locus for historically based conspiratorial musings at the crossroad where bourgeois hypocrisy and working class values intersect.

The Bank Job presents a fanciful hypothesis surrounding the 1971 Baker Street Robbery committed in London’s Marleybone district in 1971, where thieves ransacked a Lloyd’s Bank vault containing safe deposit boxes via a 40 foot underground tunnel that they dug from a nearby store front. Although walkie-talkie communications between a look out and one of the robbers were intercepted by a ham radio operator who notified the police, they nevertheless failed to pinpoint the felony’s location. This twist, coupled with the heist’s audacity, captured the media’s attention. Shortly thereafter rumors circulated that the government issued “D Notice” silenced all news coverage of the event. This action naturally begot conspiracy theories, shrouding the incident in a certain mystique. Although 4 individuals were ultimately convicted for the robbery in 1975, many people believe that, to this day, nobody knows who the thieves were, or what they were doing.

The movie intertwines this specific crime with a number of London based scandals from the 1970s. The action begins when model Martine Love (Saffron Burrows) is arrested at Heathrow with hashish in her suitcase. She is coerced by suave MI5 officer Tim Everett (Martin Lintern) to retrieve sensitive materials involving a royal peer that a cynical black militant leader named Michael X (Peter de Jersey) is using to pressure the government into dropping extortion charges against his revolutionary movement. The blackmail photos, of course, are stashed in the Baker Street vault. She convinces her ex-boyfriend, a semi-reformed thief turned shady used car dealer Terry Leather (Statham) and his mates to break into the bank for the miscellaneous valuable stored in the other boxes. Although the robbers garner the material that the spies want, they also abscond with photos taken by the proprietress of an elite (and very secret) gentlemen’s club where Members of Parliament engage in kinky role playing. Aided by a pornographer Bernie Silver (David Suchet), who handles the police protection fees for both organizations, corrupt coppers and mafia connected criminals combine forces in order to to regain their stolen assets.

The overall theory that the robbery stemmed from an undercover plot of the British intelligence services to protect royal personages began circulating the year before the film’s release. The retired Secret Service officer who made this claim, George McIndoe, served as the film’s consultant and is listed as one of its co-producers. The robbery’s connection to other scandals that get enfolded into the narrative, either by direct reference or inference, is entirely made up. They provide a lively but sordid chronicle depicting the political elite’s sexual decadence, exploitation of the poor, and their use of illicit means to cover up their indiscretions. In a typically British way, everything boils down to class: Plucky working class blokes with a touch of larceny about them confront an insidious mesh of political power and organized crime. Basically, it recasts The Full Monty as a cheeky neo-noir.

The manner in which the film deploys activist Michael X as its antagonist illustrates this point. Emulating the careers of African American separatists such as Malcolm X and Eldridge Cleaver, Michael Abdul Malik changed his name and founded the black power political movement R.A.A.S and the “Black House” community center in 1965. In 1971 he faced accusations of extorting businesses in London’s East End black community. One allegation, in which a white landlord was pressured into making payoff to X’s foundation after being placed in a metal slave collar, is depicted in the film. The activist’s legal issues made him a cause célèbre among England’s radical chic: John and Yoko even paid his bail once (earning them a brief cameo). Before the trial he moved to Trinidad where, after establishing a socialist collective, he was arrested, tried, and executed in 1975 for the murdering an associate whose body was recovered in a burial site in his compound. That grave also covered the remains of Gale Benson, The daughter of a Conservative Party M.P. and the mistress of Hakim Jamal, another prominent black power activist [For more information read V.S. Naipaul’s “Michael X and the Black Power Killings in Trinidad”]. The movie portrays Benson as an undercover MI5 agent whose affair with Jamal fronted a secret operation against Michael X, a claim that lacks plausible support. Likewise, any connection between Michael X and the Baker Street Heist is entirely speculative, and outright dismissed even by the experts interviewed on the documentary on the film’s blu-ray.

The movie implicitly references other widely reported scandals involving the London police’s vice squads and organized prostitution in the mid 70s. The protection racket involving the pimps, pornographers and law enforcement might remind viewers of the relationship between James Humphreys, a notorious sexual procurer, and high officials in the Metropolitan Police that came to light in 1972. The brothel in which M.P.s are photographed in bondage might also jog memories of the 1978 arrest of Cynthia Payne, the proprietress of the “House of Cyn”, whose life was depicted in two popular 1998 English biopics, Wish You Were Here, and Personal Services.

By invoking a large swath of underworld history, The Bank Job provides a paranoid structure linking random events from the period to a complex, if fabricated, conspiracy. At the time, readers of The Sun and its ilk experienced these sensational revelations as unconnected but pervasive examples of social decay, or as James Ellroy puts it, acts of individual moral perfidy enacted on an epidemic scale. The Baker Street Robbery, as portrayed in the film, integrates these incidents into a broader synthesis suggesting greater coordination between disparate factors than what public memory, or the historical record, indicates. Basically, the movie turns the Lloyd’s Bank on Baker Street into the Daley Plaza of 70s London criminality. As with the Kennedy assassination, ambiguous factoids start promulgating multiple sets of “secret” histories involving shadowy groups working, via the underworld of spies and gangsters, to guide the path of history. Compared to, let’s say an Oliver Stone film, The Bank Job’s speculations are fairly benign: The stakes for national security are pretty low, and the movie constitutes little more than an exercise in 70s nostalgia dressed up with contemporary swagger.

Yet the film’s paranoiac synergy also enhances the heist film’s populist appeal. Ever since the Hays Code relaxed its prohibition on depicting criminal acts, these movies have romanticized the sundry activities of “men with skills” whose willingness to break the law subverts the system that cheats them. The characters gain our respect both for their competence and our sympathy for defying illegitimate authority. The Bank Job’s interlocking multiple historical components enhances the vicarious pleasures we take from this enterprise. In re-aligning the balance of power between merciless forms of institutionalized power and scrappy working class hustlers and their communities, The Bank Job explores the moral and ethical dilemmas that result when anti-authoritarian “just” actions also promote selfish individual interests.

Let’s face it , Vogel, Michael X, and their respective crews clearly began their careers in the same vein as the more likable group of guys who steal their assets. One might easily assume, therefore, that such loose associations evolve into more sophisticated modes of integration, ultimately becoming a brutal mirror to the institutions that they fought against. Terry and his mates might, for now, be the good guys in an anti-establishment sense, but what’s to stop them from becoming part of the organized criminal establishment at some point down the road?

The Bank Job models criminality as a universal form of political power, where the rebels are co-opted into the system as long as they play the game in a way that is of service to their social “betters”. Blackmail and extortion permit the elites to defy bourgeois sexual norms for the profits of organized crime. The film’s bank robbing heroes seem semi-immune to this perversity of exploitation and power. They seek stability in marriage, respect women, value friendship, and maintain the discipline of holding down day jobs between pulling off heists. Terry might succumb to a moment of individual moral turpitude when he bangs Martine in the bank vault in violation of his wedding vows, and he might succumb to the temptation to roll back the odometers of the fancy sports cars he sells, but he and his pals uphold a particular, yet casual, code of honor to their families and neighbors.

The tabloid sensibility that informs the The Bank Job’s plot also reflects the scandal sheet’s blend of puritan morality. The good guys have their faults, but they tow an ethical line that allows them to function as respectable, of not upright, citizens in a working class community. Beyond this acceptable level of forgivable deviance, there is a darker world of hypocrisy backed by political and economic influence that represents a graver decadence. The moral rectitude bestowed upon one’s character by membership in a community immunizes one from becoming lost in the voyeuristic haze of the urban demimonde. A price might be exacted from this contact (one of the group does pay the ultimate price for the robbery), but redemption is possible. The Bank Job doesn’t transcend genre, nor is it revisionist, but it is a more complex, and mostly successful, articulation of the themes and pleasures that such crime films are supposed to provide.