Blind Reads: in which Avathoir and wallflower read each other’s favorite books without knowing a thing about them first.

I, an old man, have written this fire report. (from the last page of Young Men and Fire)

The people who get killed will never come back.

–Koyoharu Gotōge, Kimetsu no Yaiba

wallflower: After Norman MacLean retired from the University of Chicago at “the Biblical age of threescore and ten” he began a second career, really a second calling, as a writer. He published one book in his remaining lifetime, A River Runs Through It and Other Stories, and that made his reputation. Around the time of its publication, he began work on a second book and would continue working on it for over ten years until he was too sick to continue. That book was published a year after his death as Young Men and Fire, and my recommendation for it is simple: this is the greatest work of history I know, one man bringing every kind of knowledge–scientific, literary, Christian, social, historical, and a lifetime’s experience of nature–to a single event: on August 5, 1949, fifteen Smokejumpers parachuted into Mann Gulch, near Helena, Montana, to fight a fire burning there (one man was already on the ground). On August 6, all but three were dead.

Throughout, MacLean identifies himself as a “storyteller,” not a writer, not a historian or a scientist although he meets with a few of them. The Editor’s Note at the beginning sez that the three-part division of the book is MacLean’s: Part One is a fairly straightforward narrative, with backstory-type digressions, of the fire, the deaths of the Smokejumpers, and the aftermath; Part Two is about MacLean’s own long investigation into the fire (why did the fire suddenly blow up? Why was Smokejumper foreman Wag Dodge able to set an “escape fire” to save himself, and did that fire contribute to the deaths of the others?); and Part Three is a short chapter that–we’ll get to that later. All of it has the same kind of unhurried storytelling voice that MacLean used in A River Runs Through It, the kind of voice that seems to belong to the American frontier, to a time and place where the oral tradition was the dominant, maybe the only, form of culture. All through his voice and his actions, you can feel his need to do maybe the two most fundamental acts of history: to honor the dead, and to understand just what the hell happened back there in the past.

We’re gonna break down how this book works, but as this is a Blind Read, what was your reaction? (Interesting that this is our first work of non-fiction, yet it has some of the same mythic claim as American Vampire.) What did you think of the voice and the structure, two of the most particular aspects here?

Avathoir: When you first gave me this book as a suggestion back when we began planning this series, I looked up MacLean’s name swearing I had heard it before. I was proven correct, since I had seen at least some of the film adaptation A River Runs Through It at some point in my youth. So I was prepared to just settle down with some good pastoral shit, you know? Something almost quiet.

Then I got a few pages in and saw a man walk out of a fire with his skin as black as tar.

Suffice to say, the book changed in a pretty big way from then on. I read with a combination of fascination and horror, unable to believe what I was witnessing. It was like discovering, well…like Laxness’ readers must have felt when he dropped Under the Glacier on them: a totally unexpected work from a writer which nonetheless feels compatible with what came before upon closer examination.

I’m glad you mentioned honoring the dead in this, because I feel this is really the examination of what MacLean has set out to do with this book. Solving what happened (and what happens is horrific and thrilling, and makes The Perfect Storm look meek in comparison) is less what I think stumped him then the realization of how these men were alive, and then they were not, and trying to reconcile why this was. This is not the territory of a whodunit, a whydunit, but a howcouldit. MacLean understands perfectly well why the fire happened. He just is trying to acknowledge how knowing all this after the fact doesn’t do anybody any good.

This is a book then, about death, and about trying to understand what it is like, what it feels like, about trying to live through something that by definition it is not possible to live through. There have been a lot of books about death, but very few about this particular way of processing it. There are valiant attempts (Knausgaard’s My Struggle, Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me, and because I don’t want this list to be all nonfiction, The Death of Ivan Ilych, which is probably the the first modern example of this type of writing and arguably the best).

That’s just what stands out to me, and why I personally find it special. wallflower, what about you? You’ve clearly had this book on your mind a while, I’d love to hear more why.

wallflower: This book came into my life about the same time as Reservoir Dogs, and had the same effect: it awakened me to the possibilities of an art form, and a love of that form that’s continued to this day. I read this while studying history in grad school, which meant I read a lot of books that followed the academic formula of 1) find a bunch of facts; 2) put them in chronological order; 3) publish. These are works that strive for objectivity, and “objectivity” is defined as “equally boring to everyone.” Young Men and Fire was a work of history written by a particular person about particular people; it was a book that came from a passion (and a Passion) and that was present in every goddamn sentence. This was where I learned that history was an act of witnessing; like you said, this is a book about death, about something we all will go through, and how you honor the lives and deaths of others, because one day that will be you. Young Men and Fire knocked me permanently off a more academic attitude to history; in the decades of teaching history since then, I’ve always insisted on finding personal works of history to teach. (So textbook publishers, fuck you, and you can blame it on MacLean.)

Glenn Gould once said of Leo Stokowski “he had that gift which old age often enhances–the ability to state the obvious without embarrassment.” That gets at something about MacLean’s style, and it’s another influence on me. MacLean was a teacher for a full life before he started writing this; he also grew up in a time before radio, let alone television, and all that gave him the virtue of a plainspoken patience. If he uses a metaphor (like “bi-visual”) he’s gonna take a paragraph or two to explain why. If he sees something like a wave going the wrong way, it comes from seven decades’ experience on rivers and in the woods, but he’ll still tell us why. A lot of literature depends on things not being clear to the reader, and it should; but MacLean’s style is to carefully break everything down until it’s as obvious to us as it is to him. That’s infected my own writing over the last few decades, and I experience (what I arrogantly imagine to be) the same impulse: can I make this clearer? Can I state this more simply? MacLean writes about how he’s always trying to learn how to tell stories, especially if there’s a way to make them shorter, but his own writing demonstrates the virtue of making stories as long as they have to be, but no longer.

At the time I read this, I called myself an “interested atheist.” I grew up Episcopalian but more importantly, I grew up rationalist, where “reality” gets defined as “that which can be given a full physical explanation.” Another aspect of Young Men and Fire that wasn’t clear to me until some years later: this book is about compassion, a Christian compassion, something that’s also at the heart of Under the Glacier: the duty to know what cannot be known, to bond with someone else that cannot be understood. MacLean needs to make this journey, needs to go back to Mann Gulch, needs to track down the two remaining survivors (the third survivor, Dodge, died five years after the fire) Rumsey and Sallee and he needs to bring them back to where it all happened and make them witnesses to their own lives. (The chapter where he tracks them down is a short story into itself, and also good advice for any historian: “Scholars of the woods know that one of the best bibliographical references to consult is the postmistress of a nearby logging town.”) As I’ve said before, MacLean’s methods are diverse, but the desire comes his love of God and of the Creation–and that’s something much bigger and more complex than Reason.

Let’s talk a bit more about that Reason, though, before we move back into MacLean’s cosmos; let’s look at the stories of Part One (the drama of the day of the fire) and Part Two (the mystery of MacLean trying to find out about Part One). What did you think of these stories–the characters, the settings, the events?

Avathoir: At the risk of stating the obvious, I was genuinely shocked at how novelistic Part One is, while at the same time belonging clearly to the realm of nonfiction. This is very hard to do for a variety of reasons: there risks the embellishment or invention of details, or hearsay in regards to something which the author cannot possibly know. MacLean, to his great credit, treats the event of the fire essentially as an anatomy of how people do their jobs. I was flashing on Michael Mann and heist movies reading this section, seeing how someone jumps into a fire, what they have to do while inside the fire to avoid being burned to death, what they were supposed to do to put the fire out. We see training procedures, how someone becomes a smokejumper, and MacLean uses this in the same way Kubrick did basic training in Full Metal Jacket, what the men are good or bad at defining their characters more than any conversation.

Then of course, there’s the fire itself, which reads horrifically and thrillingly. We’ve had a lot of fires this year in America, whether in California or Colorado/New Mexico, and while it’s a part of the natural world (of course being exacerbated by us in multiple ways) and reading this book makes you realize how primal a fear fire is, how it’s this overwhelming, unreasonable force that will destroy what you love in an instant and then leave nothing for you to save. There is a reason God appeared to Moses as a burning bush, and unlike the eternal aspect of god and the ice in Under the Glacier, God here is fire and unconcerned with you in the terms of the Plan. This is what was all being processed through my mind as I watched the flames come closer and closer to the smokejumpers with utter horror.

And then Dodge lit the escape fire.

I actually, audibly, SCREAMED reading that. It was so unexpected. I knew of the concept of burying yourself to escape flames, but that Dodge would do something like this, and succeed, and do so with an instant realization shocked me more than pretty much any fiction could do. I tore through Part Two as a result, trying to understand how this could have happened, and realized, with a mounting dread and mourning, that Dodge did not quite know himself, which leads to Part Three. wallflower, you’ve thought about the events of this book and what happened after for much longer than I have. Take it away.

wallflower: MacLean believes in narrative to the same extent that Janet Malcolm/Joan Didion disbelieves in it (I did not use the incorrect form of the verb, if you want me to believe that Malcolm and Didion are different people, show me a picture of them in the same place at the same time. Also provide the chain of custody); if you use the tools of nonfiction rather than storytelling, you might be more accurate, that prize virtue of the Enlightenment, but you will not honor the dead. MacLean gets that these people are worthy of a great, as you said novelistic, story, and he renders that with great precision. One of the things he does well in Part One is work in little background details on the way to the fire, relying on his skill to create a world in a few sentences:

And each boy from a small town such as Darby, Montana, or Sandpoint, Idaho, was undoubtedly thinking of his small-town girl, who was just finishing high school a year behind him. She had big legs and rather small breasts that did not get in the way. She was strong like him, and a great walker like him, and she could pack forty pounds all day. He thought of her as walking with him now and shyly showing her love by offering to pack one of his double-tools. He was thinking he was returning her love by shyly refusing to let her.

Through Part One, there are passages like this about the Smokejumpers and about fires and the Forest Service, and MacLean lets them interrupt less and less. (Neal Stephenson has yet to figure this out; Michael Crichton never did.) He gets that fire is like narrative, a force that catches up to everyone; as much as Heart of Darkness, Young Men and Fire is a metaphor for narrative and a great narrative all at once, self-aware without ever losing any intensity. When the fire catches up to them and us, and “A form like a solidification of smoke stumbled out of the smoke ahead and died in the rocks. It was a four-point buck burned hairless except for the eyelashes,” it’s full-form horror, the vulnerability of the body with “flesh hanging in patches” and two men burned so badly all their nerve endings have been destroyed and they’re happy and that’s so much worse. MacLean never veers from the established facts, but chooses them so carefully and tells them so well he creates his own world from them. You could mistake this real world for great fiction.

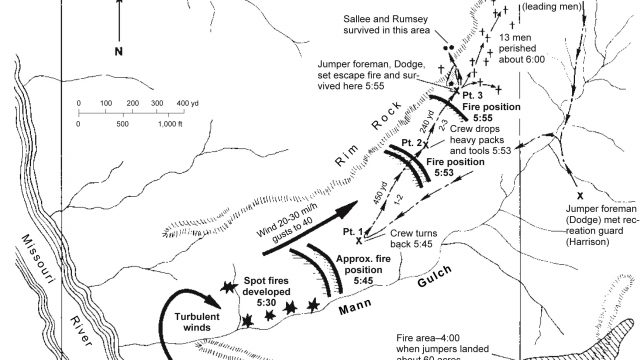

About Dodge’s escape fire, which, yes, is a total holy shit what is he doing? moment in Part One (which is the reaction of the rest of the Smokejumpers, too–one said “to hell with that!” and they all ran): Henry Thol, Jr., was the Smokejumper who got closest to making it before he died, and his father led the charge against Dodge, claiming that it was Dodge’s fire that caught up to the Smokejumpers and killed them. The review board cleared Dodge, but two recurring questions in Part Two are Was Thol, Sr., right? and Why did Dodge set that fire at all? MacLean structures Part Two as a mystery: there are wrong turns, assumptions, theories to be tested, and an explanation found. There were two winds in Mann Gulch at that moment: the prevailing wind going away from the river from the west, and the wind generated by the blowup itself sucking in oxygen, towards the river, from the east. Dodge got to the point where the two winds cancelled and set the fire there; it burned directly towards the rim of the gulch, so it couldn’t have burned towards everyone running away. In the end, like all mysteries, it comes down to the single clue that was always there: “You can safely bet that where and when Dodge lit his fire with a single ‘gofer’ match there was no wind blowing thirty miles an hour.”

Moving into Part Two, it’s the chronicle of an investigation, both social and scientific, a more straightforward work of nonfiction. I find it as compelling as Part One, a race against a slower but no less merciless clock. What did you think of it?

Avathoir: I must admit that part I didn’t get into as quickly as the first part. It’s slower to build, it needs context, and you’re kind of wondering who made it and who didn’t still and trying to reassign names. Then it starts to click, when you see the burned men, as you see Dodge try to explain and being unable to, when you have Rumsey and Salee walking through the same woods they only survived due to sheer chance…it’s not the stuff of myth, but of elegy. We are watching people confront death in a way that few do.

This is where the structure of the book starts to get a bit frustrating for me, because I wanted a whole section like that, but we get the anatomy of the fire and the decisions there of. It’s all interesting, but for me it doesn’t quite cohere. Of course, by the time Part Three came around I was more than forgiving it, and I knew right away what MacLean was doing and how. It still didn’t prepare me for the ending.

wallflower: I freely acknowledge that my interest in history and my even longer standing as a nerd made Part Two perfect for me. This is where MacLean brings several forms of knowledge to bear to figure out exactly what happened. He can take a graph developed by a fire laboratory and get a tragic narrative out of it, in five acts (I happily admit I’ve stolen this technique for teaching); he will use a picture both as an object for art-historical analysis and for the clues as to what happened on August 5, 1949; he discusses fire models and how they’re used (“They are fashioned roughly like ready-made suits of clothes.”) Where so much of our knowledge has been fragmented, it’s just sheer geeky pleasure to read someone who instinctively brings it all together, and to enjoy the company of professionals at work, as he so clearly does. Like you said, it’s a lot like a Michael Mann film.

As a narrative, Part Two most resembles Zodiac, a single amateur researcher pursuing a truth and getting closer to it, but not all of it, and we know “all of it” is not an option here. He’s not threatened by a serial killer, except for the most implacable one of all, age; on his last visit to Mann Gulch, he’s a 77-year old man on a 76%-grade slope in 120° heat, wondering if he can think straight. He conveys something all historians learn, just how hard it is to establish the simplest fact, as he and a fellow researcher come to realize that Rumsey and Sallee were wrong about where they escaped the fire. Nevertheless, he persisted, in suspenseful sequences where all the different clues align as well as they ever will: “So [the cross] was almost exactly where all three projections meet–the photograph, Dodge’s testimony, and Sallee’s memory–almost at the base of that single large tree, except it’s fallen now and the grass is tall.”

Like Zodiac, Part Two is of this world, of options weighted, judgments made, and actions taken about an event that can never be fully known. As MacLean sez, that’s enough for the historian–that’s everything for the historian–but not for the storyteller, and I wasn’t ready for Part Three either, a single chapter, the shortest in the book.

Avathoir: I am tempted, here, to not even say anything like my full articulation. What MacLean does in these ten pages is not something like a “What I’ve Learned” bit of hackery, but instead had me flashing on a very different book in almost every way: Beloved, which I was reading at the same time I was reading this. For those who are unfamiliar with how it ends, Morrison ends that novel with why the story of Beloved was not passed on by the people in that small Ohio town, and about how ultimately letting some things be a part of memory rather than history serves them better than attempting an explanation.

MacLean comes to a similar conclusion. He knows he can’t solve what happened, not really. He doesn’t have the time, and even if he did, that alone might not be enough. We are instead left with the realization that the boy Smokejumpers (and they were boys) died, and those who have died will never come back. What else is there to say?

wallflower: MacLean began his writing career with the sentence “In my family there was no clear line between religion and fly fishing”; he ended it with this chapter, where there is no clear line between religion and anything. Perhaps the defining act of Christianity is the Passion, the passing through suffering into death; and what MacLean gets, down to the rhythm of his prose, is that Christianity calls on you first to witness. At the end, he gives up all attempts to explain, even to understand; these last pages aren’t about getting into anyone’s head, but to walk as close as he can to them towards their deaths, to offer that last full measure of compassion, to tell the young men who have died (in the words of another great Christian writer) I will not send you into the darkness alone.

MacLean, then, tracks the last movements of the Smokejumpers, the way the world was narrowing (“Everything gets smaller on the way to the eternal”) and the references to the Book of Common Prayer and the Gospels and Shakespeare don’t feel planned at all; these last pages feel written in a single sitting and should be read the same way, the ritual of a man calling up everything in his life for the last effort.

The most eloquent expression of this cry was made by a young man who came from the sky and returned to it and who, while on earth, knew he was alone and beyond all other men, and who, when he died, died on a hill: “About the ninth hour he cried with a loud voice, Eli, Eli, lama sabachthani?” (“My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?”)

Over four years ago, when I began to write in earnest, when I took on another Passion for LoveFest, those words were with me and I had to pay tribute to MacLean, even if it was just part of a sentence. I was a young man when I read this book and I’m not anymore, closer now to the age when MacLean started working on it than the age when I read it, and if you don’t die young like the Smokejumpers you live long enough to see other people do it, and those truths are better called unavoidable than universal. The journey towards death, the one we all take, moves from the particulars and contingencies of Parts One and Two towards the eternals of Part Three, an ending “about as close as body and spirit can to establishing a unity of themselves with earth, fire, and perhaps the sky.”

Thank you for another great installment of Blind Reads everybody. We’ll be taking a break to finally get to Inherent Vice on The Spiral, and then we’ll be back with the third Installment “America: Interactions and Reactions”, where we’ll be discussing the first story collection and first graphic novel of the series.