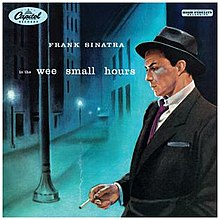

The cover of In The Wee Small Hours features a painting of Frank Sinatra leaning against a building on a street corner, lit cigarette in hand, sharply dressed and wearing his trademark fedora. (Don Draper could have been thinking of this album when he drunkenly posed with his own hat, asking Joan “Sinatra?”) Heavy shadows, cyan colors overwhelm the art deco city streets. Yet Frank isn’t focused on them. His eyes are looking down as if lost in thought, his expression one of melancholy and narrow contemplation. The artwork here is a capturing of some of the era’s aesthetic – well-tailored men in the shadows, opaque and mysterious – but also shows us what the music will be: a battered, haunted collection by a man used to his sadness.

In The Wee Small Hours is a heartbreak album, like Blood On The Tracks or Pirates, but it’s not quite an exorcism of demons and restless feelings. Frank wasn’t a rock n’ roller or a soul artist: he was passionate but he had a sense of the cool to go along with those grander emotions. Therefore Small Hours is tired, forlorn, and quietly melancholy, not crying the blues. It really is as if Sinatra lay awake, and thought about the girl…then got up and drove to the recording booth. And sang into the mic all of his exhaustion, desolation, and yearning for the person he would not have.

At the time, Sinatra was going through a separation from Ava Gardner, who he’d eventually divorce. His obsession endured, though they remained friends – Mia Farrow said that he spoke of her as if it caused him actual physical pain. Sinatra was never a stable or truly happy man anyway. He had violent mood swings, and Nancy Sinatra has noted that her father would’ve been much happier with medication and a real diagnosis, probably of manic depression. Small Hours then is a chronicling of Frank Sinatra at one of his peaks professionally and one of his lowest personally.

It’s a fascinating, beautiful album in its push and pull between stately perfection and utter heartache. There’s a sense that Sinatra refuses to allow his performances or Riddle’s arrangements to crack or go off the rails into a show of absolute devastation – that would not be the gentlemanly thing to do. That doesn’t mean the album isn’t itself devastating, its power found in the understatement, the ache of that light baritone, the hush of Nelson Riddle’s orchestration. Arguably, Sinatra became a better singer once he started acting – experience was a factor, but he started to deliver the songs as monologues and soliloquies, performing each piece of lyric, emphasizing certain words for maximum impact on the listener. (Note how in the lyric of “When Your Lover Has Gone”, he steps on “The love that you CHER-ISH/so of-ten may perish…” allowing “perish” to crumble into dust.)

Nelson Riddle’s arrangements and orchestral decisions also astonish however, and Sinatra’s work with him was undoubtedly his best. The singing and music here are in total harmony, as if Sinatra and the strings, horns, and clarinets played in deference to each other’s strengths. Like Sinatra, Riddle makes the choice to underplay while introducing new instruments at key moments in the song, augmenting what came before, such as the supple strings in “What Is This Thing Called Love”. At least until “Last Night When We Were Young”, the only song where Sinatra and Riddle truly let loose. In the climax, the singer moves the song from elegiac narrative into something louder, sweeter, sadder, overwhelmed by the pain of memory, the horns shouting in agony.

That this is the one track on the album with a real crescendo adds to the overall artistic impression of a record intentionally stripped of bravado, of strong catharsis. This is a cool jazz album at its heart and the contradiction of a brutally honest pop album that won’t allow the dam to burst has fascinated its listeners for decades. A whole other essay could indeed be written about In The Wee Small Hours as a study of Fifties repression, the product of a generation of middle class men who could seemingly only confess their feelings with alcohol and in the shadows that wrap around Sinatra on the cover. Nevertheless, the record has endured because sometimes understatement, sometimes low-key pain, is as powerful as no holds barred purging.

I used to listen to this record in San Francisco after a period where I had been essentially homeless and had my heart broken. I was twenty years old, battered emotionally, and I was mostly broke. I’d listen on my iPod, drinking cans of Forster’s at 10pm, walking along Geary Street in the Richmond District and mumbling along with Sinatra that “I’d never be the same again.” I never really was, because you won’t be after you fall in love for the first time and can’t shake those feelings, that overwhelming fire in your dumb, foolish thing you call a heart. But like Sinatra I would slowly get up and move on, and pour those passions into other work, other people, into your life. I haven’t fallen in love again. And if I do, and I get hurt once more, I’ll know what album to listen to in the restless night, when nothing and no one else will be on my mind.