Andrew Davis’ 1993 adaptation of The Fugitive has endured as a classic for a lot of reasons: the way the action never goes overboard into spectacle (and the most spectacular thing doesn’t come at the end); the intelligence of its protagonist and antagonist; the high level acting, from the leads to all the supporting players; the great hook from the original series. Something else it has in its favor: Davis, like me, is a Chicago native and he brings a sense of the place to everything he does here. (Not just The Fugitive, but many of his early films–Code of Silence, Above the Law, The Package, Chain Reaction–are set entirely or mostly in Chicago.)

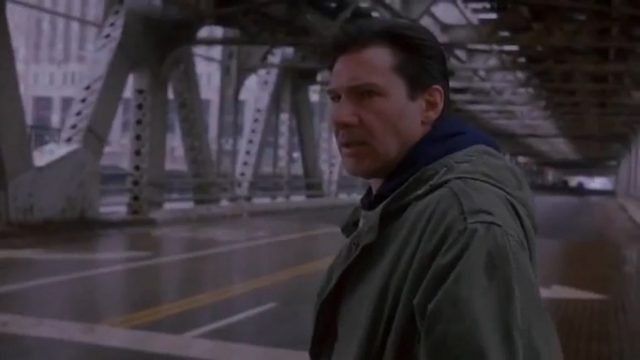

Knowing a place, especially for directors, means knowing and wanting to show the details that other people miss. Davis catches so many things that are particular to Chicagoans: the spaces between houses in the working-class neighborhoods; the metal trusses of the bridges; the old stone of the buildings; the train tracks over streets; and the gray kind of rain that almost seems friendly. It also means catching the people that are specific to a place, like casting Chicago newsman John Drummond as himself (of course Drummond would be on the scene of a high-profile murder there, barking out the report in his distinct staccato cadence) or Ron Dean as a cop. At its best, it means using these choices to further the world of the movie, in its tone and even in its plot: Dean isn’t so much corrupt here as lazy, content with the easiest solution to the case. (“Yeah, but his wife was more rich.”) He also comes back in The Dark Knight, which uses Chicago as its model for Gotham City and transposes a lot of the character of the real city into the iconic one.

There are also films that go the other way, deliberately avoiding any kind of specific connection to a place, works that are utopian in the literal meaning (“nowhere”) of the word. Creating this kind of no-place means creating a place that has emotional but not geographical specificity, and it may be harder to do than finding the details that recreate a specific place that exists. Two of the rare cases it works for me are Jane Campion’s almost Neolithic mudscape of The Piano, which works because the whole film is a jumble of times (a Gothic 19th-century story scored to unmistakably 20th-century music) and the setting is one more piece of disharmony; and David Cronenberg’s Millbrook, Indiana in A History of Violence, an abstract Small Town invaded by an abstract horror, the Unstoppable Killing Machine of so many action movies, Viggo Mortensen’s Brundlefly brought to life without a single special effect.

Knowing the location is one more aspect of detailing a movie, and you don’t have to be born there to do it, although it helps. Greta Gerwig in Lady Bird, Michael Mann in Collateral and Heat, Alexander Payne in Sideways, Sidney Lumet in Prince of the City (I leave out Woody Allen because his New York always seems to be an imagined one), David Fincher in Zodiac, the Coens in Fargo and A Serious Man, Quentin Tarantino, Robert Altman, Spike Lee and Martin Scorsese are all directors with a strong sense of place. CineGain raised this question almost a year ago with respect to cities, so let’s take opportunity to broaden it: What are your favorite places in movies? What are movies that don’t have a strong sense of place, and are actually the better for it?