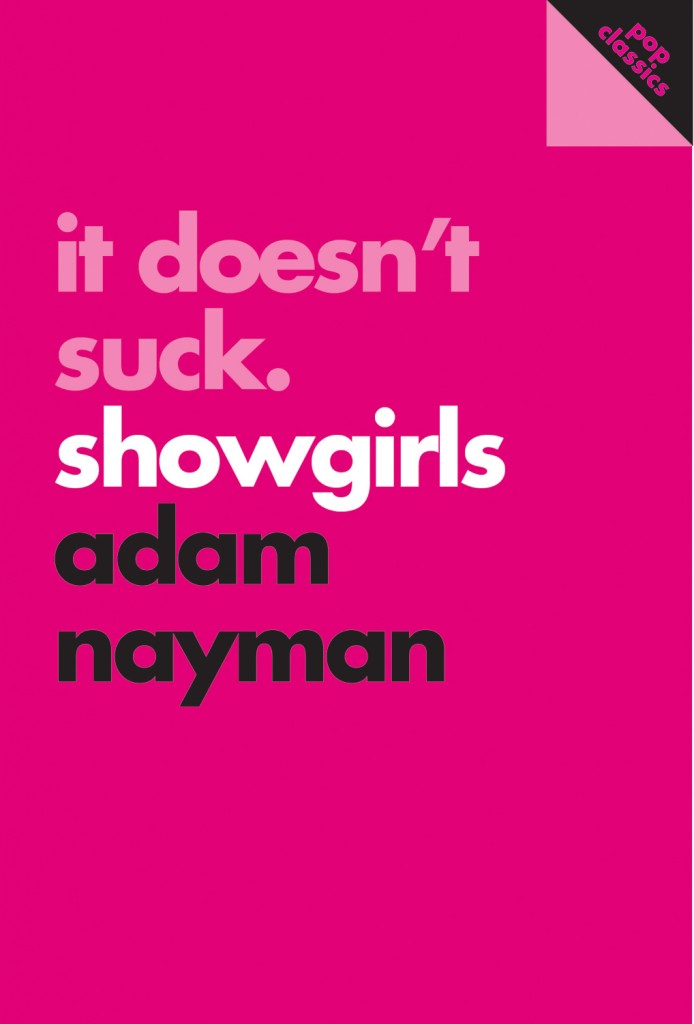

Adam Nayman’s short pop-culture curiosity, It Doesn’t Suck: Showgirls, is an attempt to reclaim Showgirls as both a masterpiece of intentional camp and a serious dramatic interrogation of the sexist structures in society. He uses a structure which opens with interfilm cultural arguments, including the history of camp and the film itself, then goes through the film chronologically before coming up with his conclusion. Whether or not you agree with Nayman’s conclusions, Nayman manages to make many fine points about the film, and points to the many many echoes, call backs, themes, and motifs that director Paul Verhoeven and screenwriter Joe Eszterhas inserted into the film. Still, some of his other points are lacking and under-developed.

Adam Nayman’s short pop-culture curiosity, It Doesn’t Suck: Showgirls, is an attempt to reclaim Showgirls as both a masterpiece of intentional camp and a serious dramatic interrogation of the sexist structures in society. He uses a structure which opens with interfilm cultural arguments, including the history of camp and the film itself, then goes through the film chronologically before coming up with his conclusion. Whether or not you agree with Nayman’s conclusions, Nayman manages to make many fine points about the film, and points to the many many echoes, call backs, themes, and motifs that director Paul Verhoeven and screenwriter Joe Eszterhas inserted into the film. Still, some of his other points are lacking and under-developed.

Nayman opens the book by interrogating the cult of Showgirls. He discusses the lovers of bad cinema, briefly touches on hatewatching (without using the term), and then proceeds to argue about the definition of camp. He points out, repeatedly, that camp is falling into two camps. The first interpretation of camp was cemented by Susan Sontag. Camp was an interrogation of mainstream culture, and could not be created intentionally. Camp was created by outsiders in order to examine the codes, depictions of codes, and consumption of codes which are used for heteronormative America. The second interpretation of camp has arisen with the new generation. In a generation where being different is OK, suddenly camp takes on an intentionality from the creators. It isn’t terrible because we intended it to be terrible. The new definition is a short circuit of ironic watching, and repurposes it for intent.

Personally, I blame Rocky Horror Picture Show, a movie which did intentionally use camp to interrogate the depictions of heteronormative codes in American b-pictures, especially sci-fi and horror tropes. The intentional use of camp, however, gave Rocky Horror a reputation for being a bad musical, which then allowed it to be reclaimed in the name of camp. So, it became a campy reclamation of a campy reclamation, and the snake ate its tail.

Adam Nayman was born in 1993, 18 years after Rocky Horror Picture Show was released. Hell, this was a mere 3 years after Rocky Horror finally made it to VHS (with a red plastic case). He was born long after Rocky Horror‘s cult was born, and even after people were starting to see Rocky Horror Picture Show as a movie that used camp as a weapon. To Adam Nayman, camp has always existed in a dual nature of either being intentional or unintentional, and it never is clear which is which.

When Nayman interrogates the cult of camp, and ironic filmmaking, he identifies a class that balks at the idea that camp was once a quality thrust upon it by viewers, rather than a quality aimed for by the filmmakers. This is the era in which The Room, which was released when Nayman was 10 years old, became the hipster’s equivalent to Rocky Horror Picture Show. Where Rocky Horror was using camp to decimate heteronormativity, The Room was a masterclass in failure. Tommy Wiseau, the creator behind The Room has gone on record saying that The Room was originally intended to be a dark comedy, but there isn’t anything funny in it unless you’re hatewatching it. If it is a comedy, what is it mocking that makes it funny?

Within this atmosphere of confusion around camp, Nayman writes a book to try to reclaim Showgirls as a masterpiece of ironic camp, using Starship Troopers as one of his markers. Starship Troopers, Paul Verhoeven’s follow-up after Showgirls, was a film that combined propagandist techniques to tell the story of a war on an insect planet (a faceless enemy). Verhoeven and screenwriter Edward Neumeier used the propagandist techniques to interrogate war, used the war to interrogate the propaganda, and challenged what we accepted as the truth. He used subtle Nazi imagery, iconography stolen from the WWII era newsreels, and the internet to challenge the dominant story of a kid who patriotically goes off to war to fight the bugs (leaving a passing footnote that the bugs were invaded first).

Of course, Verhoeven is no stranger to irony. He used irony heavily in Robocop, and in his European sexcapades, but his irony was always very easy to point out. On the other hand, Joe Eszterhas wouldn’t know irony if it bit him on the ass. Eszterhas thinks he’s a laugh riot, but really the hilarious parts are in the campy reclamations of his movies. Which brings us back to Showgirls.

Using Starship Troopers as the code to Showgirls is like using The Shawshank Redemption to interpret The Shining. Nayman depends on the fallacious statement that because Troopers is ironic, so must be Showgirls. To back up his claim, he goes through Showgirls in a linear fashion, citing examples of humor and themes. Much of his interpretation consists of, “if this is intention, could this be intentional too?”

Even so, every reclamation of Showgirls must wrap the film’s most jarring moment into its interpretation. The rape scene. Before I read this slim book, I had written the scenic routes, where I said that Showgirls has its intentional side and its camp side. They are not the same. But, I cite the rape scene as the key moment where Verhoeven’s vicious indictment shows its purely ugly and raging face in a pure form. The sequence is cruel and brutal and out of character with the melodrama-on-cocaine nature of the surrounding 2+hours. In order to properly reclaim the film, you have to spend time thinking about that scene, and what it means in the larger context, because the scene isn’t just a blip. The rape scene is the catalyst for the remainder of the movie.

Unfortunately, Nayman doesn’t have the guts to wrap the rape scene in it. He acknowledges it, but every time he tried writing about it, he would slip off to a more comforting place. There were several times he would address the scene over the course of a few pages, but then would dodge to another topic in the next paragraph. Primarily, it is for this reason that I disagree with Nayman’s reclamation of Showgirls as an intentional masterpiece. Even back then, Verhoeven knew that that rape scene wasn’t just campy fun. He had used sexual aggression in Basic Instinct, where he had Michael Douglas violently fornicate (assault? rape?) with his psychiatrist girlfriend, who commented on how brutal it was. But, it wasn’t nearly as vicious as the rape in Showgirls.

Thus, with the inability to properly address how that scene wraps into his interpretation, I think Nayman is way off.

However, all that criticism aside, Nayman does have some great qualities in assessing Showgirls as a serious piece of work. He makes many great observations on themes, reprises, dialogue, acting, dancing, cinematography, and sound. His interrogations of Showgirls as a serious work of art is top notch, and should be read for the depth he reaches. His interrogation of camp is fairly fascinating, especially because he acknowledges the two different schools of camp. If you’re obsessed with Showgirls, this book is a must read, even if you will ultimately disagree with him.