It’s only within the last ten years that popular video games have managed to stop relying on cliche. The relative newness of the medium – forty-six years since the release of Pong, thirty-nine since the release of ADVENTURE, twenty-six since the release of Wolfenstein 3D – mean we’re still discovering what it can do; innovations like Depression Quest, Gone Home and Telltale’s various outings are still getting incorporated into the grammar of video games faster than they can be developed. From this perspective, it makes sense that so many developers, not being geniuses who can instantly understand the kinds of stories video games can tell, would rely on cliche (and occasional genuine plagiarism – the first Call Of Duty recreates several iconic war movie sequences beat-for-beat and word-for-word) to fill out the ideas their stories need. I’ve been playing through the first two Max Payne games, released in 2001 and 2003, and together they demonstrate how this is the most basic act of creativity.

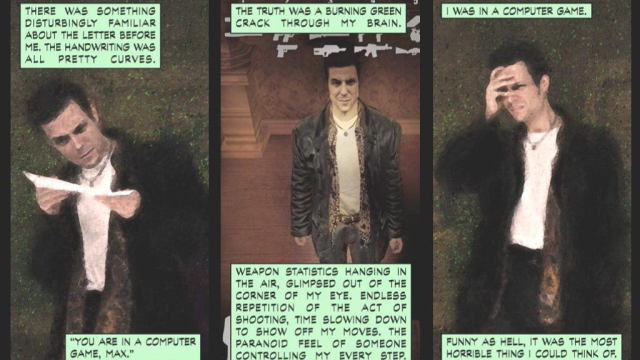

Let’s be clear, as much as I love them, these games are not particularly profound experiences. The first game begins with the murder of Max’s wife and child, and follows him as he owns his way to the top of the conspiracy responsible for their deaths; the second game veers dangerously close to sincerely emotional in conception as it follows the fallout for the events of the first game and the parts of the world that Max didn’t wipe out quickly tear themselves apart. None of the characters rise above cliche, few of the characters make meaningful decisions (Vlad, maybe), and as hard as Max tries in his awesome/ridiculous pastiche of film noir narration, nobody says anything meaningful on the world or, like, the human condition and junk. This is genre at its most generic.

(The final line of the second game comes close to being an exception, and occasionally there are lines I find to be beautiful expressions of things I believe)

But none of this really matters because there’s a fun collision of ideas going on. At its most basic, there’s a huge difference between watching a hardboiled detective own his way through dingy apartments and streets and being a hardboiled detective doing all that stuff I just said. You control the narrative; aside from being personally responsible for the ownage, you can stop and look at the scenery, and the designers reward you for this with fun setpieces, ranging from gangsters having conversations (including one where two accidentally blow themselves up), to answering machines, to simple evidence that something very strange happened in the room you were in – at one point in the first game, you stumble upon an apartment, boarded up, filled with mood lighting and porn music, with a dead guy on a bed (Max: “I didn’t even want to know.”).

What’s really interesting is the games follow through with this synthesis on a story level. The first game has an ongoing Motif™ of Norse mythology – a drug called Valkyr is taking over the streets, you fight through a club called Ragna Rock, there’s a mysterious and powerful one-eyed man named Alfred Woden, and the whole thing takes place over the course of a brutal snowstorm hitting New York City. What I think they were going for was a sense that this is a story that could quickly turn into a fantasy story before veering back into crime (at one point you fight a guy hopped on Valkyr who believes in every single evil god from Loki to Cthulhu, and Max is pretty derisive of him when he figures out what’s going on), but what it really does is inject a sense of all-pervading doom and dread to the proceedings.

The second game drops the Norse stuff and replaces it with an expansion of one of the first game’s minor aspects. Max Payne had TVs that sometimes played news reports of your exploits, and sometimes played Lords And Ladies, a parody of BBC costume dramas. Max Payne 2 has TVs playing about four or five parodies of different shows – on top of Lords And Ladies returning, there’s a cartoon adaptation of Captain Baseballbat-boy, a newspaper comic that appeared in the first game, Dick Justice, a blaxploitation show, and Address Unknown, a parody of Twin Peaks. These add, if not depth, then the illusion of depth; Dick Justice and Address Unknown parody the cheesy style (“The rains fell like all the angels in heaven were taking a piss. When you’re in a situation like mine, you can only think in metaphors.”) and the plot points of the first game respectively, while Captain Baseballbat-boy takes place in the morally black-and-white universe Max often notes he doesn’t live in. If a great story creates a diverse moral universe, this at least achieves a diverse tonal one.

Everything that the game does and does not achieve can be best seen in the iconic dream sequences. If this was The Sopranos or Mad Men, these sequences would reveal something Max is either repressing or forgetting; all they tell us is Max feels guilty over his actions, which he eloquently and frequently explains in his narration. If it was LOST, they would be a vision quest setting off Max’s next action; it’s not that either. What they do is bring together the genre pastiche (the ‘detective is rendered unconscious or drugged and has trippy dreams’ cliche being in everything from The Maltese Falcon to The Big Lebowski) and the gameplay (the sequences are simple violence-free puzzles that serve as respite from all the shooting) in such a way that both the horrific and playful tones the series plays with can come out at full force. On the one hand, some of the most disturbing, hell-like imagery in the series comes out during these sequences; on the other, so do some of the most absurd jokes.

Maybe what Max Payne has to teach us is that creativity is letting two seemingly unrelated concepts have a conversation with each other. Max Payne‘s concepts don’t have anything deep to say to one another, but it is fun to watch them talk.