There’s a bit of a running theme in children’s lit: the first book will always be the most-read and remembered, but the sequels tend to be more rewarding for readers willing to dig a little deeper. Maybe it’s because the authors, like their target audience, become more accomplished as they mature. And maybe that target audience, being children, just want to read the warm-ups over and over instead of moving on. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is what inspired the movie, but its sequels produced dozens of memorable but unremembered characters like the manic Patchwork Girl, the cuddly but monstrous Nome King, the proto-robot Tik Tok, Princess Langwidre with her interchangeable heads, and the gender-bending, regal Ozma, all rendered by the elegant pen of illustrator John R. Neill. Thousands of children learned to read from The Cat in the Hat, but it’s The Cat in the Hat Comes Back that gave us one of the most memorable images of Dr. Seuss’s career, the continuously multiply little cats that live under each other’s hats (and the children’s increasing bewilderment as even more of the little things show up still makes me laugh even as a grown-assed man). Alice in Wonderland is the source of most of Lewis Carroll’s iconic characters, but Through the Looking Glass gave us Tweedle-Dee and Tweedle-Dum, some of Carroll’s best poetry with “Jabberwocky” and “The Walrus and the Carpenter,” and saw him take his topsy-turvy logic to surreal, dreamlike, and even nightmarish heights.

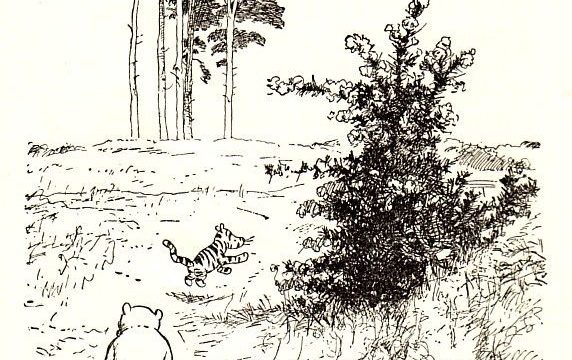

And then there’s The House at Pooh Corner. The original Winnie-the-Pooh is pretty near untouchable in its classic status, but A.A. Milne’s return to the Hundred-Acre Wood saw him develop it in far greater depth. If Winnie-the-Pooh had a simple story about Pooh and Piglet laying a “Pooh trap for Heffalumps” The House at Pooh Corner has them fall into what they decide must be a “Heffalump trap for Poohs” complete with several poems and a miniature play. This volume also introduced the series’ most popular supporting player, Tigger, and gave the Disney studio most of the source material for the three short films that would end up defining the characters more than Milne ever did. (It was impossible to read Pooh’s dialogue in any voice but Sterling Holloway or Jim Cummings’ – that version of the character has so thoroughly colonized our consciousness that earlier adaptations, like this one, where he has a childlike sped-up voice, just sound wrong).

You can see Milne’s maturation as a reader by comparing the previous volume’s introduction with this one’s “Contradiction.” Milne explains that title, in a Carrollian bit of wordplay:

An introduction is to introduce people, but Christopher Robin and his friends, who have already been introduced to you, are going to say Good-bye. So this is the opposite. When we asked Pooh what the opposite of an Introduction was, he said, “The what of a what?” which didn’t help as much as we had hoped, but luckily Owl kept his head and told us the opposite of an Introduction, my dear Pooh, was a Contradiction; and, as he is a very good at long words, I am sure that’s what it is.

We can already see how comfortable Milne has become with his characters and their highly individualized voices (you could delete all the dialogue tags from The House at Pooh Corner and still have no trouble following it — but if you did, you’d miss some of the best parts, as we’ll see later) and how much room his readers’ familiarity gives him to stretch out. The first Introduction was a rambling, sentimental piece with the kind of cutesy-pie picture of Christopher Robin he would grow to resent in adulthood. This one comes together at just over a page, building to a more subtle and effective emotional climax:

There, still, we have magic adventures, more wonderful than any I have told you about; but now, when we wake up in the morning, they are gone before we can catch hold of them. How did the last one begin? “One day when Pooh was walking in the forest, there were one hundred and seven cows on a gate…” No, you see, we have lost it. It was the best, I think.

Christopher Robin was growing up right along with his father. This passage is a picture of the book in miniature, building to the moment he has to put away childish things. By 1928, the stories had expanded beyond the conceit of being stories Milne told to his son or adaptations of the adventures Christopher Robin would make up for his toys. Where the first volume’s stories often opened with Christopher Robin, here he tends not to show up until the end of each one as a deus ex machina figure, more parental than childlike. Instead, Milne splits his keen observation of the child’s mind between the other characters. Pooh and Piglet display the innocence of childhood with a clear-eyed vision that recognizes that it can lead to a kind of well-meaning casual cruelty, as when Pooh tells his friend, “What you have said will be a Great Help to us, and because of it I could call this place Poohanpiglet Corner if Pooh Corner didn’t sound better, which it does, being smaller and more like a corner. Come along.” Tigger, even more so, is true to life in his innocent destructiveness, while Roo stands in for an even younger child, excitedly taking in everything around him to the point his dialogue almost becomes stream-of-consciousness. Rabbit, Owl, and Eeyore, who have “brains,” instead of “fluff that had blown in there by mistake,” are often interpreted as the killjoy adults of Milne’s world, but they are more like children who desperately want to seem adults, play-acting maturity in imperfect imitation. After all, Rabbit respects Owl “because you can’t help respecting anyone who can spell Tuesday; even if he can’t spell it right.” Eeyore works himself into a lather over showing off the “Learning” he picked up from Christopher Robin, throwing a jealous fit when he discovers it is “A thing rabbit knows! Ha!” Piglet’s response shows Milne’s jaundiced views of the foolishness of adulthood.

“I think —” began Piglet nervously.

“Don’t,” said Eeyore.

“I think Violets are rather nice,” said Piglet. And he laid his bunch in front of Eeyore and scampered off.

The House at Pooh Corner, like so many of the great children’s books, is Romantic at heart, a Blakeian Song of Innocence. Though Milne is writing for children, he is also advocating, like the older poets, for his adult readers to return to the innocence and wonder of childhood. Like its most direct forebear, The Wind in the Willows, The House at Pooh Corner offers a beautiful dream of a synthesis of childhood and adulthood that can never quite exist in reality, free from both parental control and adult responsibility. Mister Rat believed there was “nothing half so much worth doing as simply messing about in boats.” Christopher Robin says “what I like doing best is Nothing…going along, listening to all the things you can’t hear, and not bothering.” (Which makes you wonder about Pooh’s favorite cuss being “bother”…) In this book, living well isn’t something you can work for, but a meditative state of easygoing openness. I doubt it’s a coincidence that two consecutive stories begin like this, with Pooh aimlessly, dreamily pondering what to do with his day:

One day when Pooh was thinking, he thought he would go and see Eeyore, because he hadn’t seen him since yesterday. And as he walked through the heather, singing to himself, he suddenly remembered that he hadn’t seen Owl since the day before yesterday, so he thought that he would just look in at the Hundred Acre Wood on the way and see if Owl was at home.

Well, he went on singing, until he came to the part of the stream where the stepping stones were, and when he in the middle of the third stone he began to wonder how Kanga and Roo and Tigger were getting on, because they all lived together in a different part of the Forest. And he thought, “I haven’t seen Roo for a long time, and if I don’t see him today it will be a still longer time.” So he sat down on the stone in the middle of the stream, and sang another verse of his song, while he wondered what to do.

The other verse of the song was like this:

I could spend a happy morning

Seeing Roo,

I could spend a happy morning

Being Pooh.

For it doesn’t seem to matter,

If I don’t get any fatter

(And I don’t get any fatter)

What I do.

The sun which had been delightfully warm, and the stone, which had been sitting in it for a long time, was so warm, too, that Pooh had almost decided to go on being Pooh in the middle of the stream for the rest of the morning, when he remembered Rabbit.

This, meanwhile, is how Rabbit’s story begins:

It was going to be one of Rabbit’s busy days. As soon as he woke up he felt important, as if everything depended upon him. It was just the day for Organizing Something, or for Writing a Notice Signed Rabbit, or for Seeing What Everybody Else Thought About It. It was a perfect morning for hurrying round to Pooh, and saying, “Very well, then, I’ll tell Piglet,” and then going to Piglet, and saying, “Pooh thinks—but perhaps I’d better see Owl first.” It was a Captainish sort of day, when everybody said, “Yes, Rabbit” and “No, Rabbit” and waited until he had told them.

He may be a Bear of Very Little Brain, but Pooh’s approach seems far more attractive. (And that’s why this piece went up days later than it said on the schedule – I was just being true to the spirit of the work! Yeah, that’s the ticket.) It certainly becomes apparent when Eeyore tries to write a poem for Christopher Robin’s farewell party that his pursuit of adult respectability has taken the poetry from his soul. After all, “the best way to write poetry, is letting things come,” while people like Eeyore and Rabbit have to scramble around working for them.

In our postindustrial world, it is, unfortunately, a fairly privileged view. You have to be as busy as Rabbit to make a living unless all your needs are already provided for (there’s a reason Milne’s master Kenneth Grahame wrote about the aristocratic “River Bankers” instead of the blue collar “Wild Wooders”). But then, that’s a privilege that belongs most of all to children, so The House at Pooh Corner transcends class politics to become a timeless dream of independence from parental control for children, and of independence from care where adults who are “Friendly with Bears can find it.” That’s what invests Christopher Robin’s news that “I’m not going to do Nothing anymore” with such powerful sadness.

Not everyone was a fan. Dorothy Parker’s memorable review as “Constant Reader” sees her barely get through the first story before informing us “And it is that word, ‘hummy,’ my darlings, that marks the first place in The House at Pooh Corner at which Tonstant Weader Fwowed up.” She seemed to have a but of a feud going with Milne; when she filled in for Robert Benchley on the New Yorker’s theatre beat, she closed out her review of Milne’s play Give Me Yesterday (titled “Just Around Pooh Corner”! )with the message, “Robert Benchley, please come home. Whimso is back again.” It’s easy to see how such a legendary cynic would be immune to the stories’ charms, but in other ways, it’s a bit ironic given how similar the two writers’ humor can be. They’re both master of the dry wit, of making jokes all the funnier by hiding the punchlines, or, to use some Milne-esque language, writing in a “Did-They-Really-Just-Say-That?” sort of way. True, Parker was full of acerbic New York bile where Milne couched his statements in polite Britishism, but it’s still not difficult to find the parallel between Parker describing a “low but futile décolletage,” and “Owl looked at him, and wondered whether to push him off the tree; but, feeling that he could always do it afterwards, he tried once more to find out what they were talking about.”

Pooh’s belief that “Everyone’s alright, really,” was almost too much for this Tonstant Weader (and if that seemed bizarrely naive from a veteran of the Great War, it looks even more wrong-headed after the ninety years of historical horrors since the book’s publication). Fortunately, the rest of the text belies that childish optimism (to be distinguished from its more admirable, childlike qualities. Look, if you can come away from this book without being tempted to play around in the sandbox of the English language, either you’re a better man than I or you didn’t really read it.) As we saw in Owl’s little inner monologue, there’s a layer of clear-eyed cruelty under all the cuteness. What never struck me as a child, but which quickly turned him into the highlight of the book on re-reading, was just how passive-aggressive Eeyore is.

“I don’t know how it is, Christopher Robin, but what with all this snow and one thing and another, not to mention icicles and such-like, it isn’t so Hot in my field about three o’clock in the morning as some people think it is. It isn’t Close, if you know what I mea —not so as to be uncomfortable. It isn’t Stuffy. In fact, Christopher Robin,” he went on in a loud whisper, “quite-between-ourselves-and-don’t-tell-anybody, it’s Cold.…And I said to myself: The others will be sorry if I’m getting myself all cold. They haven’t got Brains, any of them, only grey fluff that’s blown into their heads by mistake, and they don’t Think, but if it goes on snowing for another six weeks or so, one of them will begin to say to himself: ‘Eeyore can’t be so very much too Hot about three o’clock in the morning.’ And then it will Get About. And they’ll be Sorry.”

The passiveness is far more important than the aggressiveness. For a book aimed at the very youngest readers, Milne’s wit is dizzyingly complex, avoiding rim-shot punchlines and hiding inside layers of evasion most writers wouldn’t trust kids to sort through. “In Which It Is Shown Tiggers Don’t Climb Trees” actually shows the title character going out of his way to never admit that. Instead, we get this relayed conversation from Roo when Tigger gets too spooked to climb back down: “So we’ve got to stay here forever and ever — unless we go higher. What did you say, Tigger? Oh, Tigger says if we go higher we shan’t be able to see Piglet’s house so well, so we’re staying right here.” There’s a reason the Disney adaptations have made such heavy use of voiceover narration, to the point of having the characters interact with the narrator and the words on the page around them. These stories don’t matter so much for what’s being told as the way it’s told. The aside during Rabbit and Owl’s conversation is just one example; Pooh falls into “a small piece of the forest that was left out by mistake,” Tigger is described “hiding behind trees and jumping out on Pooh’s shadow when it wasn’t looking.” And, taking us back to the dreaminess of the stories, there’s “a drowsy summer afternoon, and the Forest was full of gentle sounds, which all seemed to be saying to Pooh, ‘Don’t listen to Rabbit, listen to me.’” It’s an afternoon like that when we leave Pooh and Christopher Robin.

But wherever they go, and whatever happens to them on the way, in that enchanted place on the top of the Forest, a little boy and his Bear will always be playing.