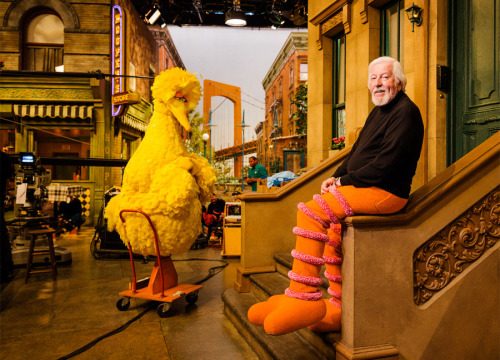

He does have credits not as Oscar or Big Bird. Just, you know, not many of them. He’s been playing the roles since well before I was born, though he’s training his successors now. After all, he turns eight-four on Tuesday. (His upcoming birthday is not why I chose to write about him and is merely a happy coincidence.) He did some professional work before hooking up with Jim Henson, but for nearly fifty years now, he’s been a completely unrecognizable part of millions of children’s lives.

In 1962, Jim invited Spinney to come “talk about the Muppets.” It’s not just him; that doesn’t sound like a job offer. But it was, which he realized after the fact. In 1969, the invitation came again, and this time, he took it. It got him in on the ground floor of a little public television educational program called Sesame Street. It’s taken him all over the world. China. Japan. Australia. The White House, repeatedly. And, as it happens, Vromans Bookstore in Pasadena, California, where my mom got his autobiography signed for me.

My older sister, as a child, called it The Big Bird and Oscar Show. I’m sure she’s far from the only child who did. Big Bird and Oscar are definitely cornerstones of Sesame Street. Though neither of them were in the beginning as they quickly became. In the first days of the show, Big Bird was a country bumpkin and Oscar was orange. The changing of Oscar from orange to green was not just a change in acrylic fur; it was a settling in. I’ve seen some of those first-season episodes, and it feels as though there’s something a bit off about the characters that would be adjusted as time passed.

I’m also one of the few people who really misses Bruno. He, like Big Bird, was a full-body puppet—of a garbage collector, whose job it was to carry Oscar around. He was mute, not least because it was difficult for Spinney to manage shifting back and forth between two voices. (My understanding is that, when two of his characters appear in a single scene, one character’s voice is tape recorded.) But it was a way for Oscar to get around. But the puppet decayed, and he was not replaced; what do you do?

Both of what I consider to be the two most moving parts of Sesame Street history rely on Spinney’s acting ability. One is a little less known; when I was in college, Big Bird’s nest was destroyed in a hurricane. Spinney wandering around the Street saying, “My nest . . . my home!” is completely devastating, and I really like that, when Gordon says everything’s all right, Big Bird pushes back, because everything is not all right. I like even more that Gordon admits that, no, it isn’t. Because of course it isn’t.

More even than that, of course, is one of the most famous scenes in Sesame Street history. When Will Lee died, the Powers That Be at the Children’s Television Workshop decided to kill off Mr. Hooper. The problem with that was explaining death to their audience—and they chose to do so through Big Bird, who’d always had a special relationship with Mr. Hooper. The adults in the scene are tearing up, because they’d lost a friend and were having to act through it. And Spinney is not tearing up until it’s time, which is probably one of the hardest things to do. I’ve been crying myself at that scene for thirty-five years.

Treat my kids to Sesame Street DVDs; consider supporting my Patreon!