Japan was the best thing that ever happened to Lafcadio Hearn. The half-Irish, Greek-born, London-educated writer had tried to forge a career as a journalist, essayist, and fiction writer in the New World, first as a newspaperman in Ohio, then as a general man of letters in New Orleans, then in the Caribbean, absorbing along the way the very worst in trendy purple prose styles. Here, for example, is the opening of one of his Cincinnati sketches, “Violent Cremation”:

“One woe doth tread upon another’s heel,” so fast they follow. Scarcely have we done recording the particulars of one of the greatest conflagrations that has occurred in our city for years than we are called upon to describe the foulest murder that has ever darkened the escutcheon of our State.

Here, by contrast, is the opening of the first and most famous of the Kwaidan tales, “The Story of Mimi-Nashi-Hōïchi” (“Hōïchi the Earless”) written after his move to Japan:

More than seven hundred years ago, at Dan-No-Ura, in the straits or Shimonoséki, was fought the last battle of the long contest between the Heiké, or Taira clan, and the Genji, or Minamoto clan. There the Heiké perished utterly, with their women and children, and their infant emperor likewise–now remembered as Antoku Tennō. And that sea and shore have been haunted for seven hundred years.

Kwaidan is a model of elegance and restraint from a writer not known for either and is rightfully considered a classic, while the 1965 film adaptation remains one of the high-water marks of arthouse horror. How did Hearn get there? And given the dry laconicism of the original, how do we read the sometimes flamboyant, thoroughly artificial film that resulted?

I’m being a bit unfair to Hearn here. True, very little of his American work has lasted — his dismal novel Chita, about a hurricane destroying a southern Louisiana community, vomits up almost 5,000 words on scenery before it introduces its first character — but others, like his 1883 investigation of Louisiana’s “secret” Filipino community for Harper’s Magazine or his collections of local recipes, have at least proven invaluable to historians.

I’m being a bit unfair to Hearn here. True, very little of his American work has lasted — his dismal novel Chita, about a hurricane destroying a southern Louisiana community, vomits up almost 5,000 words on scenery before it introduces its first character — but others, like his 1883 investigation of Louisiana’s “secret” Filipino community for Harper’s Magazine or his collections of local recipes, have at least proven invaluable to historians.

But it was his failed assignment to Japan that determined his legacy. Hearn chased a newspaper commission gone wrong and found himself teaching English as a schoolteacher in Matsue, eventually marrying and settling down in his new adopted country. Meanwhile, Hearn’s prose style once again absorbed local aesthetics, shedding the purple elaborations in favor of an increasingly plain and direct prosaicism. Within a few years, he had become a kind of unofficial ambassador of Japanese culture to English-speaking readers, producing works on history and cultural (pop-)anthropology aimed at de-mystifying the East, though the more lasting impact might have been the reverse: twentieth-century Japanese readers have been far more likely to know his name and legacy.

Still, English readers did gobble up his work for a time, especially his collections of “weird tales.” That’s only one translation of the word kaidan, stylized as the more archaic “Kwaidan”, which are literally “ghost stories,” but not necessarily in the horror genre. The stories that Hearn published are not original to him but not quite translations, either: some of the tales are fusions of different variations of common folktales, and in others Hearn’s own narrative voice sometimes intrudes to provide context or elaboration. His first Kwaidan was such a hit that Hearn continued to produce “weird tales” in various collections, including even tales from China. In fact, only two segments in the film Kwaidan are from the collection of that name.

Sixty years after Hearn’s death, the great Japanese filmmaker Kobayashi Masaki put together this omnibus film of four “weird tales” published by Hearn (and they are definitely Hearn’s versions rather than adaptations directly from folk material: screenwriter Mizuki Yoko includes even Hearn’s narrative intrusions). It was a bit of a gamble from a filmmaker known mostly for sweeping historical realism in works like The Human Condition (1959-1961) and the blunt violence of Harakiri (1962). Among his usual collaborators, Kobayashi brought along a pair of vital contributors: his cinematographer Miyajima Yoshio, who composed the ravishing colors that made Kwaidan famous, and the great avant-garde composer Takemitsu Toru. The resulting film’s look and sound are as far from cinematic realism as it gets: nearly all of the film’s “exterior” shots are interiors with clearly artificial backdrops, with scenes set to screeching snippets of sound that seems to resist coherence. The result is a sort of perfumed claustrophobia, nothing like the understated restraint of Hearn’s retellings. It’s an astute choice that made Kwaidan the memorable work that it is.

Kwaidan‘s open credits unfold over images of ink dropped in water, a sign both of the film’s commitment to its literary origins and its pretensions toward visual abstraction. The first segment of the film, “Black Hair,” is based on a story called “The Reconciliation” from one of Hearn’s later collections of “weird tales.” It is the most bare-bones of the Kwaidan segments, largely confined to a single, dilapidated estate, and it relies greatly on a pair of great actors: Aratama Michiyo (one of The Human Condition‘s leads) and Mikuni Rintaro. It also establishes Kobayashi’s strategy for adaptation: the first 20 minutes of the segment adapts a single page of text, just over 300 words, by expanding and elaborating on Hearn’s version of the story.

For example: in Hearn, the samurai protagonist leaves his first wife and impoverished life for a second, whom the text describes in a sum total of two adjectives: “The character of his new wife was hard and selfish.” That terse line, along with a note that the marriage was loveless, is literally all the author says about this second wife. Kobayashi has to illustrate this visually, so the film invents scenes that conform closely to those two adjectives: we see the new wife caressing silk, abusing servants, and berating her husband. Expansion here is a necessary condition of adaptation.

The more radical change comes at the end. The punishment of Hearn’s thoughtless samurai derives from efficient fairy-tale logic: he eventually returns to his first wife only to wake up the next morning next to a corpse — she had died from starvation after he abandoned her many years before. His guilt is his judgment. In the film, the punishment is protracted and, though more horrifying, somewhat less logical: the house seems to collapse around him Usher-like, he begins to age rapidly, and her coil of black hair materializes wherever he looks, eventually strangling him (?) in the end. The filmmaking style shifts appropriately, from the long and steady camera shots of the exposition to the canting, dynamic shots of the finale. Reality has been superseded by expressionistic fantasy.

The stunning second segment is “Woman of the Snow,” based on Hearn’s Kwaidan story of the same name, “Yuki-Onna.” Hearn’s retelling is again a model of efficiency: in its brief three or four pages, we meet woodcutter who is spared by a malevolent snow spirit on the condition that he never tell anyone about their encounter. Later, on the isolated road home, he meets a young woman named O-Yuki (whose name contains the word for “snow,” natch.) He brings her home, marries her, and has children, but as the years pass… well, you can guess where it goes from there.

Here, Kobayashi’s staging of the story shows Kwaidan at its most inventively surreal. To highlight the otherworldliness of the spirit encounter, he has the woodcutter (The Human Condition‘s protagonist, Nakadai Tatsuya) lost among swirling clouds that seem to contain eyes, watching him as he struggles through the snow. It’s a gorgeous, bizarre touch, so much so that the eventual encounter with the snow spirit (Kishi Keiko, from Ozu’s Early Spring), set to shrieking solo strings, feels like a culmination rather than a sudden apparition. It also sets up the woodcutter’s eventual broken promise: everything about the first act feels like a dream, so why shouldn’t he treat it as such, so many years later?

“Woman of the Snow” was cut from the original American release of Kwaidan, in part to give the film a more manageable length for distribution. A strange decision, since it is (apart from “Hoishi”) the film’s best and most memorable segment. Kobayshi’s use of visual motif is the segment’s strongest aspect: to underscore the snow spirit’s continued vigilance, the director repeats the sky-eye motif throughout, as if an ineffable Something is continuing to watch the woodcutter long after their earthly encounter. In the segment’s terrifying finale, the watcher is no longer a vaguely eye-like swirl, but an unambiguous manifestation of a violently angry spirit.

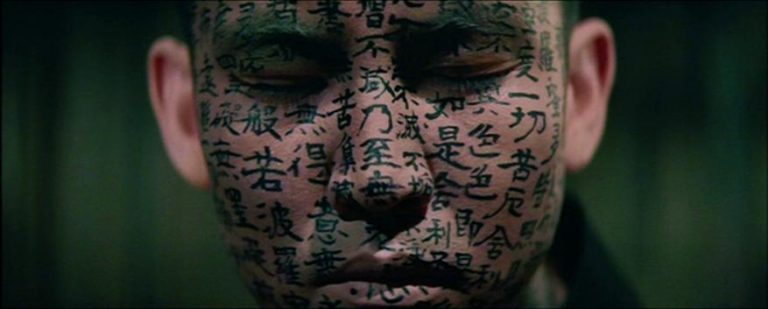

Segment three is “Hoichi the Earless,” justly famous for the image of the script-covered monk of the title. It is also the first segment to break with collection’s more conventional justice-based morality. Where the first two protagonists are punished for violating their promises, the blind bard Hoichi only saves his life by confessing a secret he was supposed to keep: every night, he has been entertaining a court of demons who intend to rip him apart after his last performance. Sadly, the monks who use magic talismans to save his life overlook one crucial detail…

Kobayshi expands on Hearn’s brief history lesson at the beginning of the story by overlaying different elements from the text: the historical background is sung in bardic style, while the visuals blend storybook/theatrical battle sequences with antique paintings of the battle and “real” images of the desolate seashore that remains today: aesthetically, we are unmoored from any particular historical perspective and can appreciate the material at a more primal level. Its bold, fiery backdrops, swirling fog, and unreal sets are there to ease us into the ghost story that follows and lay the groundwork for Hoichi’s eventual performance of the demons’ deeds. (You can watch the whole opening sequence here.)

The rest of the segment shows Kwaidan at its very best. Kobayashi blends the more conventional horror elements, like shadows and fog, things that go bump in the night, and spirits in will-o’the-wisp form with the kind of sumptuous and surreal technicolor fantasy that’d make Douglas Sirk jealous, creating an otherworldliness that really feels like a literal other world. There are so many brilliant touches in the segment — Hoichi’s performance for the demons is one of the great visual spectacles in cinema — but I don’t want to spoil any, except to note that Kobayashi smartly cast superstar and Kurosawa regular Shimura Takashi as an elder monk, because who wouldn’t confess his darkest secrets to him? Meanwhile the violent culmination draws from the kind of bluntness we see in Kobayashi’s Harakiri: it will make you wince.

The fourth and final segment, “In a Cup of Tea,” comes from one of Hearn’s later collections. As an adaptation, it faces the highest difficulty level of the set: it is (purposefully, pointedly) unfinished, trailing off just as story seems to approach its climax. “The rest of the story,” Hearn tells us, “existed only in some brain that has been dust for centuries.”

Kobayashi’s solution makes for, unfortunately, the least satisfying of the Kwaidan adaptations. He treats Hearn’s introduction and conclusion as literal dialogue among a publisher and writer, and solves the problem of “ending” by employing a hoary horror cliché: the reflection in the water is no longer just a writer’s tale, but has jumped to the “real” world, too! Earlier in the film, the segment might have had a greater impact, but it’s an awfully limp conclusion to a film with such highs.

That’s not to say it doesn’t have its moments, the best of which is undoubtedly the samurai’s confrontation with three ghostly retainers, who barely seem to move (other than blinking in and out of existence) as he slashes at them with increasing desperation. Kobayashi also uses some unusual camera tricks, like a lighting/editing effect that seems to erase the retainers but keep their shadows moving along the walls. It’s nifty if not entirely satisfying.

So what do we make of this as adaptation? As material, there are enormous differences between the simplicity of Hearn’s retellings and the sometimes gonzo colors and stylization of Kobayashi’s film. Yet I’d argue that Kobayashi is doing something that even Hearn might approve of: rather than adapting the plain text as it is, he’s exploring the kinds of images and sounds that mind creates after reading and ruminating on the stories, in other words, the things we dream about when we fall asleep reading “The Story of Mimi-Nashi-Hōïchi” or “Yuki-Onna.” Our imagination already “fills in” the ellipses in Hearn, and Kobayashi adapts those ellipses.

All that is to say, Kwaidan‘s artificiality is adaptation-in-spirit aimed at creating the kind of satisfied shudder that Hearn approaches through laconicism. Just as Hearn shed his overwrought sensibilities as he absorbed contemporary Japanese culture, Kobayashi used Hearn to rediscover a kind of elemental artistry — drawing not just from the primary color palate, but from traditional Japanese theater and painting — that years of commitment to political filmmaking had somewhat stagnated. It’s a strange marriage that blended two unlikely trajectories, through some incalculable alchemy, into a sui generis work of art.