Everyone knows about the M&Ms, but very few people know why.

It’s a famous story, one that would almost be mythological (“If the M&Ms didn’t exist, we would have to invent them”) if it weren’t true and confirmed by the band. In articles and anecdotes about rock star excesses and the absurd riders rock bands insist on when touring, the M&Ms are always one of the most frequently cited– and one of the most misunderstood.

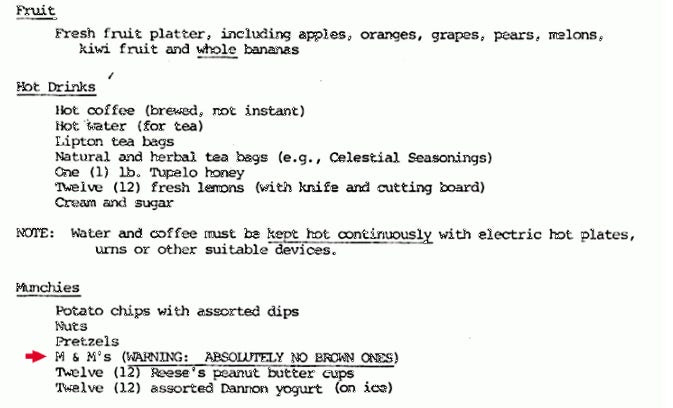

As the story goes, one of the riders Van Halen included in every touring contract in the David Lee Roth years– one that, if not met, would void their obligations to perform the show while still receiving full pay– was that the green room be stocked with a bowl of M&Ms, with one very specific request:

Of course, when this got out, along with Roth’s standard behavior of making a scene and trashing the dressing room upon discovering a brown M&M, the rider was mocked, a sign of the rock star as Caligula: petulant, excessive, and pointless except as a way to wield power over others for something trivial. The M&Ms served a real purpose, though, as Roth disclosed in his autobiography, Crazy From the Heat:

Van Halen was the first band to take huge productions into tertiary, third-level markets. We’d pull up with nine eighteen-wheeler trucks, full of gear, where the standard was three trucks, max. And there were many, many technical errors — whether it was the girders couldn’t support the weight, or the flooring would sink in, or the doors weren’t big enough to move the gear through.

The contract rider read like a version of the Chinese Yellow Pages because there was so much equipment, and so many human beings to make it function. So just as a little test, in the technical aspect of the rider, it would say “Article 148: There will be fifteen amperage voltage sockets at twenty-foot spaces, evenly, providing nineteen amperes …” This kind of thing. And article number 126, in the middle of nowhere, was: “There will be no brown M&M’s in the backstage area, upon pain of forfeiture of the show, with full compensation.”

So, when I would walk backstage, if I saw a brown M&M in that bowl … well, line-check the entire production. Guaranteed you’re going to arrive at a technical error. They didn’t read the contract. Guaranteed you’d run into a problem. Sometimes it would threaten to just destroy the whole show. Something like, literally, life-threatening.

The brown M&Ms were, then, a test for the local promoters and production crew. Were they diligent and attentive enough to detail to properly prepare for a Van Halen show, or would they be sloppy in a way that could cause massive structural damage, get someone injured, electrocuted, or even killed?

It’s quite appropriate that David Lee Roth be the center of the M&Ms controversy. Like the rider itself, Roth seems like a stupid, ridiculous caricature of rock star excess but is much savvier and more self-aware than he lets on. Roth played up his persona and antics, vocally, on stage, and in the media, because it’s what worked best with the band: Eddie Van Halen’s larger-than-life guitar work needed a frontman of equal bombast, one who wouldn’t get lost in Eddie’s shadow, and Van Halen itself needed that kind of showmanship to propel the entire band to the heights it was capable of, both critically and popularly. (As Roth himself said about the stories that he caused untold sums of damage to venues because of the M&Ms, when the truth was that most of the damage was caused by the promoters’ failure to get their venues up to code: “Who am I to get in the way of a good rumor?” Roth knew that for a rock band, any press was good press.)

Van Halen’s rotated a number of singers over the years– and, as the band nears forty years since the release of its first album, has become more of a family affair, with Eddie’s son Wolfgang replacing Michael Anthony on bass in 2006– but I don’t think the band has ever topped its original lineup or the first album it recorded. Roth’s party-boy persona and vocal excesses were the perfect complement to Eddie Van Halen’s outsized and out-of-this-world guitar playing, a steady rhythm section of Anthony and drummer Alex Van Halen (Eddie’s brother) anchoring the music and allowing DLR and EVH to be released to maximum effect.

When Roth left Van Halen in 1985 after six albums and was replaced by Sammy Hagar, the band settled into much more traditional rock-band fare, taming some of the glorious excesses and runs of Eddie’s guitar playing1, while Hagar’s singing (and the songs themselves) more or less abandoned the sense of wild nights and living on the edge, and focused on… love ballads. The very first Van Hagar single: “Why Can’t This Be Love?” (Even the title itself suggests a certain yearning; Hagar’s looking for love and hoping he found it. Roth was just looking for a good time, and he definitely found it.) That would be followed by such tracks as “Love Walks In,” “When It’s Love,” and “Can’t Stop Loving You.”

1 – to be fair to Hagar, Eddie had decided he wanted to start incorporating synthesizers and keyboards into the band’s sound before Hagar joined– witness 1984’s (and 1984‘s) “Jump,” the band’s only #1 single on the Billboard Hot 100. Indeed, this was a major reason for the rift forming between DLR and EVH that would eventually lead to the former leaving the band.

The “love” single from Van Halen? “Ain’t Talkin’ ‘Bout Love,” a rocker explicitly about DLR’s preference for casual sex. As the chorus says, “My love is rotten to the core,” and that attitude continues through the rest of the album, as “love” is only mentioned in terms of sex (e.g. “Feel Your Love Tonight”) or with disdain. There’s only one real example of a character feeling love, and that’s “Jamie’s Cryin’,” wherein Roth is narrating in the third person about a young woman (possibly a teenage girl) who wants a serious relationship with a guy but knows all she can get is a one-night stand. A tale of how having emotions caught up in sex leads to heartbreak. (Perhaps, even, a tale about how love is something for teenage girls, not rock-and-rollers.)

More than anything, this early incarnation of Van Halen made visceral music. If Van Hagar was The Americans, then Diamond Dave’s Van Halen was The Shield.2 Whether turning a classic like the Kinks’ “You Really Got Me” into an overheated, overdriven (in a good way) banger emphasizing the lust, or the rock-climbing-by-way-of-parkour out-on-a-limb sensation of “Eruption”‘s impossibly fast, impossibly high guitar runs, this version of Van Halen made you feel their music more than the later incarnations, took you on a roller-coaster ride along with them. There’s a reason so many Van Hagar songs were about love, and so many DLR Van Halen songs were about sex: One’s an emotion, an unquantifiable sentiment; the other is a visceral, physical experience. That difference sums up the experience of those two versions of Van Halen as much as anything, explains why the David Lee Roth version was always up-tempo and propulsive, while the Sammy Hagar version preferred middling tempos with unexciting synthesizers in place of Eddie’s guitar theatrics. (No comment on the Gary Cherone version.) You don’t even have to agree with Roth’s perspective to recognize that it was the perfect complement to Eddie’s guitar, that the two of them together ascended to greater heights than either ever could (or would) alone. As dumb as Roth’s shtick was, his version of the band was clearly the head rock to Van Hagar’s butt rock.

2 – this is a technique called “writing to your audience.”3

3 – and this is my attempt at an Alan Partridge impression.4

4 – and this is my attempt at a David Foster Wallace impression.

Of course, persona isn’t everything–a well-written character played by a bad actor is going to be a bad performance. It worked because of Roth’s particular charisma and vocal skills. He seemed like a guy partying excessively with would be a great time, unlike, I dunno, the lead singer of Buckcherry5. And his yelps and runs added the perfect sense of knowing showmanship to the music: Excessive, and a little cheesy, winking yet sincere: “We both know this is over the top, but deep down you also know it’s more fun this way.” On songs where the guitar work was (relatively) more pedestrian, like “Atomic Punk,” Roth’s vocals keep the energy level high. His first lines on the album, on opener “Running With the Devil,” seem to lay out the mission statement of the Diamond Dave persona: “I live my life like there’s no tomorrow.”

5 – Not to hate too much on Buckcherry; “Lit Up” is one of the best songs about doing cocaine at capturing what it feels like to do cocaine. Still doesn’t seem like a guy I’d want to do it with, though. And everything else they’ve done is terrible.

An outsized character like Diamond Dave was the perfect complement to the maximal guitar skills of Eddie Van Halen, who could perform astoundingly crunchy, overdriven riffs–“You Really Got Me,” “Jamie’s Cryin'”– little touches of flair to spice up a song– check out some of the flourishes on “I’m the One”– as well as incredible feats of technical wizardry– “Eruption,” the song that introduced the term “two-handed tap” to the masses. If you’re not familiar, the technique essentially involves, instead of fretting notes with one hand and picking with the other, using both hands to play notes as a series of hammer-ons and pull-offs on the fretboard. Eddie’s lightning-quick precision with this technique allowed him to play faster and more dense scales and solos than anyone else working in rock and roll, and the second track of the album, the aforementioned “Eruption,” was the coming-out party for his skills. Eddie Van Halen didn’t invent the two-handed tap, but with “Eruption,” he brought it into the mainstream.

From the very first Van Halen album, Eddie was already one of the most technically accomplished, capable, and flamboyant guitarists of his era, and indeed, Van Halen might be the purest expression of that ability. Unlike many of the “guitar gods” of the 80s– your Steve Vais, your Joe Satrianis, your Yngwie Malmsteens– and certainly aided by the presence of Roth and the band, Eddie’s guitar skills never come across as clinical or masturbatory. The songs are killer, and while they certainly showcase Eddie’s guitar playing, they don’t exist simply to show it off. Notably, his ability to do so much on guitar at such a high speed is what allows the songs to remain up-tempo, driven, and engaging; any slower-paced moments feel like the breather on a rollercoaster before the next drop. And much like a rollercoaster, it can feel like it’s over all too soon, clocking in at a tight 35:34.

Above all, Van Halen is never boring, the cardinal sin of a hard rock band. The music from start to finish is energetic, driven, and alive. Sure, it’s a little excessive, but isn’t excess what we want from our rock stars? Van Halen shows a band fully leaning into the maximal aspects of rock stardom and stadium rock, pushing their biggest and best musical weapons to their furthest extremes, in a way we wouldn’t see again until nearly a decade later, on a similarly bombastic and acclaimed debut: Guns N’ Roses’ Appetite for Destruction. The last track’s title, “On Fire,” is a good two-word summary of the feeling of listening to Van Halen.

Watch David Lee Roth explain the “Brown M&Ms” rider himself: