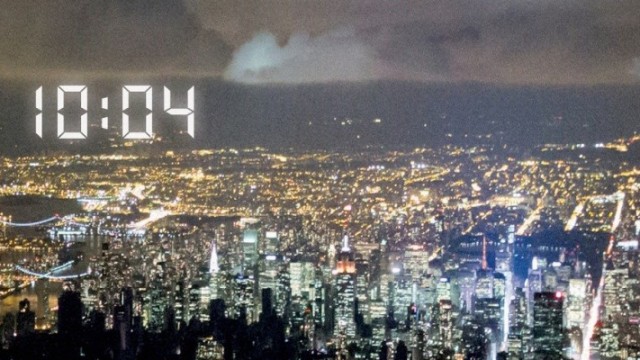

10:04, the second novel from Ben Lerner, is decorated with a photo of the glittering NYC skyline. The book is slight (it clocks in at 240 pages), but the image is indelible. The novel, like the city itself, promises everything and more between its covers. Is it a condensed magnum opus or just a storm in a teacup? As much as I want to say the former, it ultimately ends up being the latter. The novel (the titles comes the scene in Back to the Future where lightning strikes the clock tower) explores a range of themes, from global warming to artificial insemination, elaborate ideas of fraudulence to Kony 2012. What it fails to deliver a truly pleasurable, or even particularly memorable reading experience. This is a novel whose objective, first and foremost, is to gather acclaim and win awards. Or, in the words of the protagonist’s literary agent, ‘publishers pay for prestige.’ If that is the end goal, then 10:04 is one of the finest books of 2014.

To those unfamiliar, Mr. Lerner is a rising star in the literary scene. He’s an English professor, an acclaimed poet, and according to his bio on the inside of the dust jacket, ‘he has been a Fulbright Fellow, a finalist for the National Book Award for Poetry, a Howard Foundation Fellow, and a Guggenheim Fellow.’ This is excluding the praise for his debut novel, Leaving the Atocha Station, which was awarded the 2012 Believer Book Award. Lerner is no stranger to acclaim, and perhaps he has become a bit caught up in the adoration. How else can one explain his almost willfully tenebrous metafictional exercise? The book has moments of stark beauty and insight, but is so verbose in its seemingly endless philosophizing (particularly near the end where the final 70 pages feel like 300) and navel-gazing, a much-needed piquancy never manifests.

The novel’s ravenous hunger for prestige and honor is evident on the very first page, as the nameless narrator (closely modeled after Mr. Lerner himself), describes in grandiose, borderline anthropological detail, of walking along an ariel greenway in New York following an exorbitantly priced lunch. The lunch, a celebration of the narrator’s likely six-figure publishing deal for his second novel (just like real life!), consisted of ‘baby octopuses the chef had literally massaged to death.’ He continues, ‘we had ingested the impossibly tender things entire, the first intact head I had ever consumed, let alone of animal that decorates its lair, has been observed at complicated play.’ This is the sum of Lerner’s much vaunted prose: the ornate and academic figuratively massaged into turgidity. One can be forgiven for feeling an overwhelming urge to have a dictionary on hand, and Lerner’s ease with which he dispenses his elaborate vocabulary at least illustrates he is not a hack desperate to armor his schlocky prose with fancy words pulled from a thesaurus. But, the end result feels distant, dry, and needlessly ostentatious.

Prose aside, the novel is undeniably rich in thought. One recurring theme in 10:04 is an impending apocalypse caused by global warming. It casts a lugubrious mood of the book; if everything is going to eventually end, why do we go about our business? I’ll presume Lerner was inspired by Beatriz Perciado and Steve Roggenbuck, a Spanish philosopher and an Internet poet/vlogger, who both stated the end was coming, and we must find a way to make our time memorable. Lerner takes this idea and applies it through a fictionalized version of himself; his fictional avatar opting to endlessly relate his Serious Thoughts™ to the reader . No event is too minuscule for Lerner to tortuously dissect for gravitas. For example, it may interesting to think about the chain reaction of pleasure and pain when consuming highly intelligent invertebrate, and how it fits into a world of seeming limitless possibilities, even though it will all end due to our own carelessness and hubris. But, it doesn’t always make for the exciting, engaging reading. It’s thought-provoking, sure, but given how much as Lerner mines his own life, his novel can feel like a hit-or-miss collection of essays, coated with a thin veneer of fiction. Similarly, it can read like a suffocatingly self-indulgent Livejournal entry. The divide between ‘this sounds really cool and profound in my head’ and ‘this sounds awkward and excessive on the page’ is, more often than not, lacking within the book. In short: sometimes Lerner’s musings click, in their exaggerated intellectual fashion, and other times they feel flat and tedious.

This is not to say there aren’t moments of beauty and insight in the novel. Some scenes find the frequently elusive balance between humor, insight, and Lerner’s precise dissection. At one point, the nameless narrator attends a dinner party, where he slyly pokes fun at an internationally acclaimed author who spends the evening blathering about his own genius. It’s not terribly original, but the laughs are welcome. In the novel’s best scene, the narrator describes seeing the art piece, The Clock (a 24 hour film that uses clips from countless films, all set in real time), with his friend. He notes the irony of checking his watch during the screening when the film explicitly tells him the time. He states, ‘When I looked at my watch to see a unit of measure identical to the one displayed on the screen, I was indicating that a distance remained between art and the mundane. Everything will be as it is now… just a little different.’ It’s the best part of the novel, a moment that ripples through and addresses the fundamental, perhaps needless divide between art and life. In another scene, the narrator explores a collection of art, which for whatever odd reason has been deemed worthless and unfit for the market, and asks how did these pieces go from ‘art’ to mere objects. That is what Lerner wants the reader to contemplate when reading his novel; if the book borrows quite a bit from his own life, what does it say about us in how we separate our lives from fiction (art)? It’s a fascinating question, and a shame the novel doesn’t take it further.

Unfortunately, these moments are few and far between. Lerner’s largely onerous attempts at humor, such as a wacky trip to donate sperm, coupled with his compulsive need to find profundity in everything becomes enervating in the extreme. Lerner’s a talented writer, but it feels like he is afraid that his work won’t be taken seriously, so he is constantly on guard to defend and prove his genius. In the Los Angeles Review of Books, Maggie Nelson calls 10:04 ‘a generous, provocative, ambitious Chinese box of a novel.’ I would personally say it’s more like being lost in the Hall of Mirrors; you either find the dizzying multiplications of self exhilarating, or it’s all a high-concept gimmick that fails to impress.

For as much as the novel focuses on what Lerner thinks of the world, it’s a blessing it avoids becoming a narcissistic affair; he’s self-deprecating enough to avoid appointing himself as Savior and Critic of The World. Even then, his self-obsession, his ‘everything is happening through me‘ approach in the novel, all feels over done. He’s a bright fellow, and if Mr. Lerner can a way to center his almost intimidating intelligence on something other than his navel, I would read it in a heartbeat.