This essay analyzes a single scene from “Parricide” in terms of style; for the full review of the episode, go here. Scenic Route #1 engaged with the morality of The Shield and The Sopranos; #2 analyzed the character of Ronnie Gardocki.

The five and a half minutes between two commercial breaks in the middle of “Parricide” may be the shortest act The Shield ever did, and it’s one of the only acts that’s just one scene. (The end of “Chasing Ghosts” was another.) This scene, where the story takes a final turn and heads up the onramp of the We’re All Fucked Expressway, shows The Shield’s style at its most effective, and most invisible, a careful manipulation of time, space, and points of view.

Although director Guy Ferland gets my full praise here, the style of The Shield doesn’t belong to any single director; this isn’t an auteurist show. (More on that in two weeks when we discuss the finale.) Many guest directors and actors described how they had to learn the style when they came to work on the show, how it was more immediate and energetic than what they were used to, with a lot of decisions made on the fly. The style could best be described as theatrical and immersive; the cameras are handheld and almost always in the same space as the performers, so we are seeing what would happen if we were right there. (Omniscient, overhead perspective is almost never part of the style here; neither are the kind of trick shots so favored by Breaking Bad.) The style gives The Shield so much of its energy and intensity, because we’re denied the aesthetic, judgmental distancing of camerawork. There’s only what people do, and us seeing it. What makes this particular scene such an exemplar of Shield style is how it uses that style to give us the feeling of immediacy, but carefully parcels out its information for maximum suspense.

This scene in “Parricide” relies on a particular detail of the architecture of the Barn. The listening post for the interrogation rooms is down a “hallway” (really a balcony and a landing for a staircase) from one of them. The doors for the two rooms look to be about twenty feet away from each other, and they’re set at right angles to each other. Someone emerging from the listening post would turn right and walk only a few seconds to be at the interrogation room. We’ve seen this detail used several times before; the first example was in “Dragonchasers,” when Dutch emerged at the end and walked by everybody who’d been watching in the observation post applauding him. This particular scene gets set up by a moment in the previous act when Shane goes to the interrogation room to talk to Two-man, and the camera watches him go down the “hallway,” then pans over to the observation post and the monitor, simply and explicitly showing the two locations, their relationship to each other, and what the monitor shows. It’s the kind of thing necessary in a television show, where you can’t count on the entire audience having seen the entire series.

The opening of scene places all the characters except for Two-man and Vic (he’ll show up shortly) in the same space, on the floor of the Barn, discussing strategy. There are six characters here and at least four different agendas: Dutch and Billings want to break Two-man, with Billings additionally needing to prove his worth as a detective (Vic chewed him out earlier about his laziness); Ronnie wants that too, he’s also trying to figure out if Shane was behind it, and if not, why he was targeted; Claudette’s trying to manage her detectives (including Julien); and Shane desperately needs to find a way to undercut everybody. One of the things we get right away from the staging is that there’s no way he can do that, since everyone can see him.

The interrogation room, listening post, and monitor in the listening post create the potential for a great variety of shots, but The Shield doesn’t go overboard with them. All the shots are about medium length, occasionally a little closer, and they follow the pattern of who is talking or listening. It’s not like the extremely intense, subjective sequences in “What Power Is. . .” (Aceveda and Juan) or “Strays” (Dutch and Falks), because this sequence doesn’t turn on any psychological question. The only question is “will Two-man give up Shane?” which will transform the whole series if the answer is “yes.” Every single time there’s a cut to Shane listening, it ratchets up the tension.

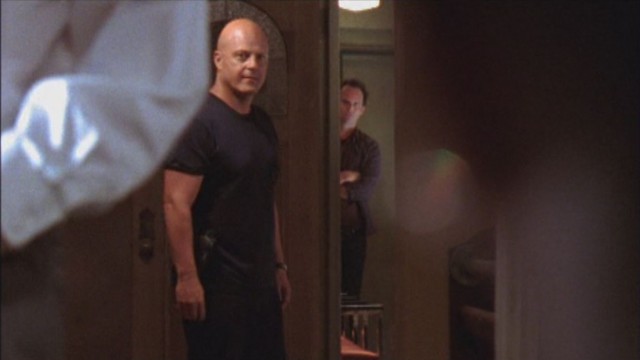

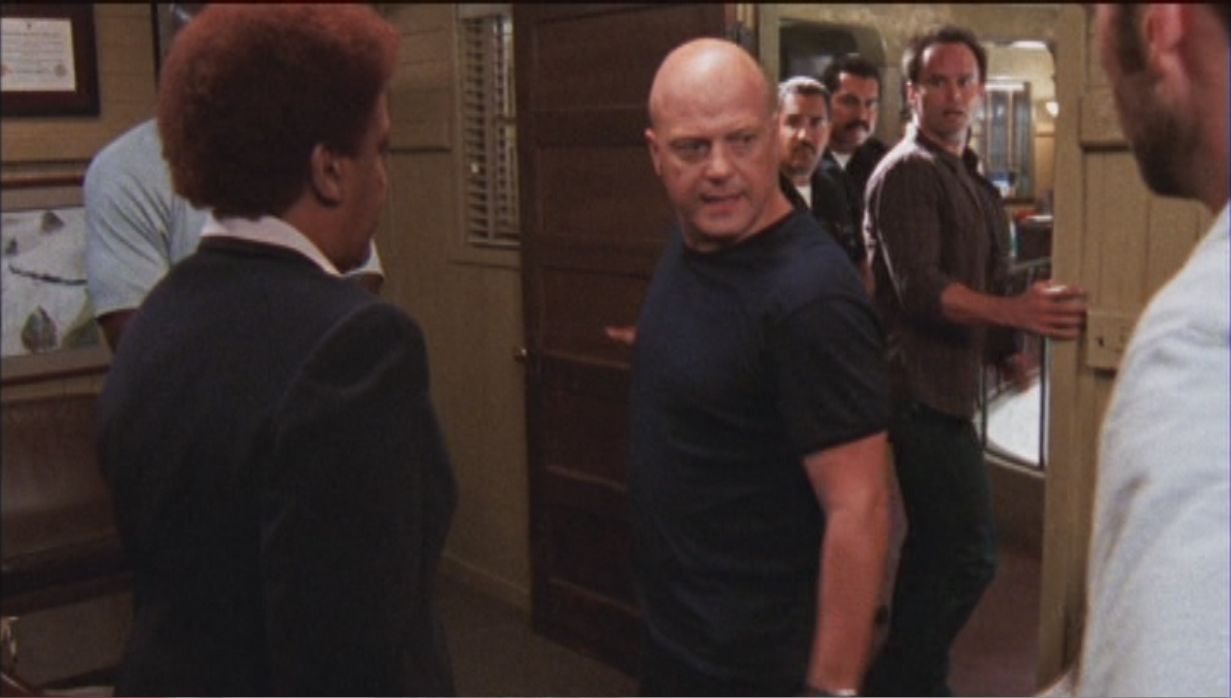

Enter Vic. (Shane’s “bukkake party” line is one of those moments when the writers are just trying too hard to push the basic-cable limits.) Shane argues that he and Julien should go in for the interrogation; he’s most likely hoping that he can get Two-man alone again. Unfortunately for Shane, Vic one more time improvises a great plan: “instead of producing the real gun we don’t have, why don’t we produce the fake witnesses we do?” Michael Chiklis is a great person to put in the center of this room: chunky and bald, he’s physically, visually different from everyone else. The staging helps to sell the strength of his idea; it’s also a believably busy, crowded shot without being overwhelming.

There’s a moment here that shows how much the style belongs to everyone, directors, camera operators, and actors. At one point, we’re looking right at Vic and Shane’s directly behind him, out of sight, and Goggins shifts position just a bit and we can see him; I’m pretty sure Goggins realized the camera couldn’t see him and without drawing any attention made himself visible. It’s something that shows a real awareness on his part of how a scene gets made and what he needs to do.

Vic heads to the interrogation room to put his plan into motion, giving Shane a friendly whap on the chest as he does it. This part of the scene is the trickiest, relying on showing four points of view but withholding one. After Vic pulls Dutch out and says “so here’s what we’re gonna do,” we cut away from them. It’s here that the Barn’s architecture comes into play. There’s a straight line from Two-man to Shane, with Dutch and Vic more or less in the middle. The shots cut from 1) Shane’s POV on Two-man, to 2) Two-man’s POV on Shane, and what we can see is that although Shane’s in Two-man’s line of sight, Two-man’s looking at Dutch and Vic, not Shane. (masterofsopranos noted a similar effect in the final scene of The Sopranos, noting that Tony has a few moments where he looks right at Guy in Members Only Jacket but doesn’t see him.) We next see Shane passing his hand under his chin, trying to throw Two-man a “shut up!” sign, and then a cut to Shane from 3) Ronnie’s POV, and then a reverse cut to Ronnie’s reaction, showing that he’s getting suspicious but isn’t fully sure yet.  We also get a shot of 4) Billings’ POV on Two-man in the interrogation room, and a similar reverse shot to Billings trying to understand. We’re put in the position here of Shane, Ronnie, Billings, and Two-man, each of them trying to see something, and each of them trying to figure out what’s going on based on what they see. That’s why it’s necessary in these shots that we don’t see what Dutch and Vic are saying to each other. If we did, we would lose our identification with the other four characters. We finally cut back to a close shot on Vic saying “so I want you to smile at me like we’ve got this bastard hung to the cross, and thank me like you really mean it,” and then a close shot on Dutch doing exactly that. (Since it happens so rarely, I’m a total sucker for any kind of Dutch/Vic collaboration.)

We also get a shot of 4) Billings’ POV on Two-man in the interrogation room, and a similar reverse shot to Billings trying to understand. We’re put in the position here of Shane, Ronnie, Billings, and Two-man, each of them trying to see something, and each of them trying to figure out what’s going on based on what they see. That’s why it’s necessary in these shots that we don’t see what Dutch and Vic are saying to each other. If we did, we would lose our identification with the other four characters. We finally cut back to a close shot on Vic saying “so I want you to smile at me like we’ve got this bastard hung to the cross, and thank me like you really mean it,” and then a close shot on Dutch doing exactly that. (Since it happens so rarely, I’m a total sucker for any kind of Dutch/Vic collaboration.)

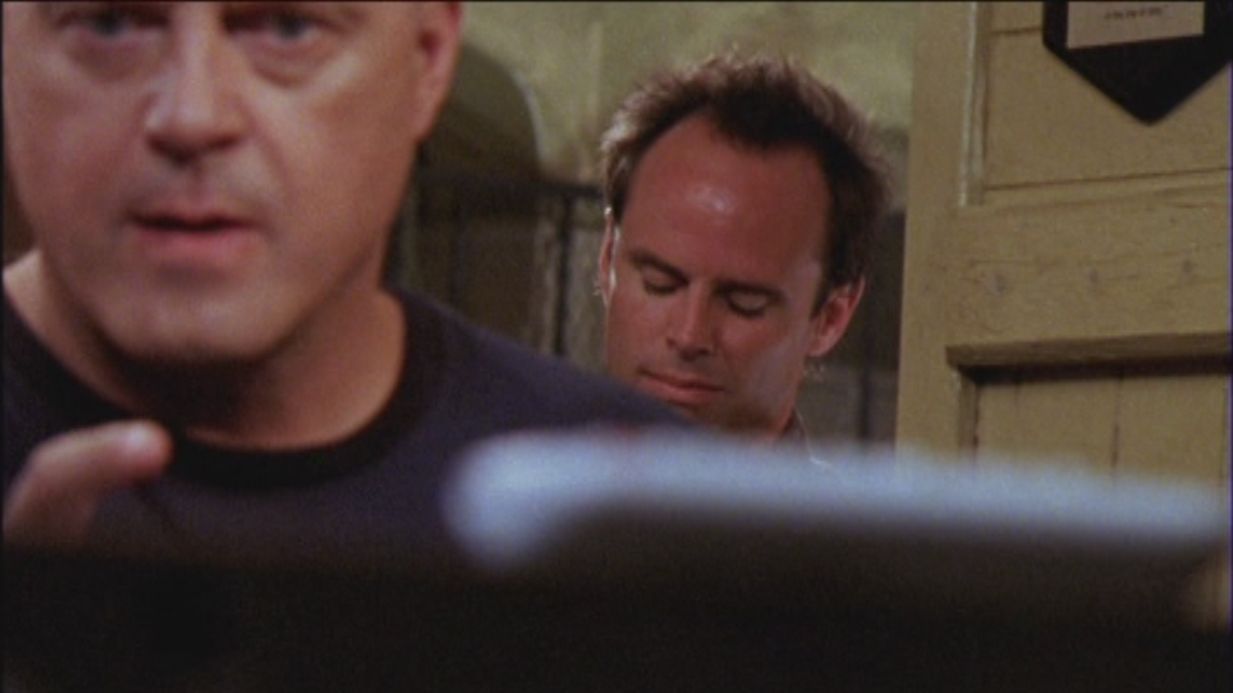

Vic’s plan was to tell Two-man that Capuchina and Farrah had given him up. Two-man, of course, hadn’t told them anything but he’d have no trouble believing that they’d claim it, one more example here of what happens when you try and rule only through violence and dominance. There’s also a good moment of looking at Billings in the interrogation room–he didn’t hear the plan but picks up on it quickly. The climactic moment here, as Two-man breaks (“come on, it’s right in front of you, shithead, take it”) doesn’t play out in the interrogation room, because it’s not about him. In fact, we don’t see that moment at all, we see it entirely through the faces of Vic and Shane. It’s one of The Shield’s most often-used elements of film grammar: the rack focus, keeping two objects at different distances from the camera in the same frame and shifting the emphasis by changing the focus. The scene has Shane behind Vic (Shane’s in the doorway), and the focus shifts from Vic to Shane and then back. Shane only reacts when the focus is on him, and all he does is close his eyes and lower his head a little, and that’s enough to let us know he’s realized he’s out of options. There’s nothing big about his reaction, and since it’s in front of so many people, it shouldn’t be, just a minimal “well, I’m fucked now.” When the focus shifts back to Vic and we see Vic is completely focused on the monitor, that’s when Shane says, so quietly, “right back,” and starts walking away.

Now we get about as classic and agonizing a suspense sequence as The Shield has ever done, based in one of the oldest cinematic practices, crosscutting. This one goes all the way back to DW Griffith, cutting between two actions so we have to wonder which will finish first. (Think lady-tied-to-the-train-tracks-while-hero-rides-to-save-her. You would cut between the approaching train and the racing horse.) Here, the two actions are Shane leaving and Two-man confessing. We see Shane leaving in a series of medium shots in motion, which serve to emphasize the distance he still has to go to get out of the Barn; closeups would let us see his face more clearly but that’s not necessary, we know how much trouble he’s in. That also contrasts with the more static shots of the interrogation and the reactions, and it’s where the quieter style for the interrogation pays off. Those shots are calmer, and they make the shots with Shane in them more frantic. Two-man’s dialogue is so wonderfully protracted, delaying the moment when he reveals the identity of who coerced him. That plays on what we know but the characters don’t; Dutch and Billings don’t rush Two-man because they have no idea it’s going to be Shane. We also see a long, slow closeup of Vic literally recoiling, taking a step back from the monitor as he realizes what happened. The two actions become so suspenseful and so damn funny because we’re all thinking (and some of us were yelling it at the TV) “IT’S SHANE! JUST SAY IT! AAAAAAAA” while Shane’s simultaneously trying to get the hell out of there and not draw attention to himself.

Now we get about as classic and agonizing a suspense sequence as The Shield has ever done, based in one of the oldest cinematic practices, crosscutting. This one goes all the way back to DW Griffith, cutting between two actions so we have to wonder which will finish first. (Think lady-tied-to-the-train-tracks-while-hero-rides-to-save-her. You would cut between the approaching train and the racing horse.) Here, the two actions are Shane leaving and Two-man confessing. We see Shane leaving in a series of medium shots in motion, which serve to emphasize the distance he still has to go to get out of the Barn; closeups would let us see his face more clearly but that’s not necessary, we know how much trouble he’s in. That also contrasts with the more static shots of the interrogation and the reactions, and it’s where the quieter style for the interrogation pays off. Those shots are calmer, and they make the shots with Shane in them more frantic. Two-man’s dialogue is so wonderfully protracted, delaying the moment when he reveals the identity of who coerced him. That plays on what we know but the characters don’t; Dutch and Billings don’t rush Two-man because they have no idea it’s going to be Shane. We also see a long, slow closeup of Vic literally recoiling, taking a step back from the monitor as he realizes what happened. The two actions become so suspenseful and so damn funny because we’re all thinking (and some of us were yelling it at the TV) “IT’S SHANE! JUST SAY IT! AAAAAAAA” while Shane’s simultaneously trying to get the hell out of there and not draw attention to himself.

That leads to one of the funniest scenes of the series, the sort of thing “that only happens in real life and great fiction,” as Darin Morgan sez, Shane’s last obstacle to fleeing, Paula signing him up for the softball jersey. (We’ve seen, by the way, that this is an annual event back in season five.) Shane has that all-too-human (and all-too-Shane) moment of trying to do something trivial when he needs to do something hugely important–you can see the two parts of his brain fighting each other here. (My favorite moment is his “uhhh, you pick?”) It’s so funny and so intense because by now he’s been revealed (I also love Dutch’s “Shane Vendrell?” as if there are other Shanes in the Barn) and Vic, Ronnie, and Julien are racing towards him. (Julien says “sorry!” to Claudette like a Simpsons character–“awww, Shane just fled the Barn! And you just know when they catch up to him it’s gonna be good!” Claudette’s what-the-hell-is-going-on-here reaction is great too.) One side of Shane’s brain finally wins and he finishes the conversation with “look just pick the goddamn number and shove it up your ass!” leaving Paula to say “what cactus is up his ass?” as Vic and Ronnie run by. The scene ends in the Barn parking lot, Shane gone, Vic and Ronnie isolated in space, looking at each other. It’s an almost musical conclusion, with a climatic long shot of everyone (the only shot in the entire sequence that’s from any kind of omniscient, detached perspective), and the few last shots of Vic and Ronnie like a coda. It’s a visually calm moment of frantic characters, telling us that nothing will ever be the same again.