Many critics consider Ran Akira Kurosawa’s final masterpiece. In 1985, after ten long years ruminating in Kurosawa’s mind, Ran was finally completed and must have felt like a revelation to its audience and Kurosawa himself. Kurosawa had once been a prolific director: he had made fourteen films between 1950 and 1965. But Ran was only Kurosawa’s fourth film in twenty years. The seventies and eighties were a difficult time for Kurosawa. His films either met a lukewarm response from both critics and audiences or he couldn’t find the financial backing to even make a film. It wasn’t until Kagemusha, in 1980, that Kurosawa would find success again (with financial help from George Lucas of Star Wars fame as well as Francis Ford Coppella). With the success of Kagemusha, which Kurosawa considered a “rehearsal” for Ran, he managed to find financial support from French producer Serge Silberman. With an astounding $12 million budget, Ran was the most expensive Japanese film at the time.

And it shows.

Ran an epic story of fathers and sons, of power and greed, of revenge and acceptance, of life and death. It’s a meditation on life, with an emphasis on aging and violence. Kurosawa made Ran in 1985 when he was seventy-five years old. While he would live for another thirteen years, I’m sure his own mortality weighed heavily on his mind. Kurosawa had already explored these themes in Ikiru, about a man diagnosed with terminal cancer who decides to do one last good act before he dies, and with the beautiful Red Beard, about a young, arrogant doctor who slowly comes to learn the importance of human connection. But those films are optimistic, probably the most optimistic films in Kurosawa’s career. After Red Beard, in 1965, which everyone, Kurosawa included, marked as the end of an act in his career, things take a dark turn.

As the 1960s ended, Kurosawa got involved in the production of Tora! Tora! Tora!, a film that detailed the attack on Pearl Harbor from both the American perspective and the Japanese perspective. He was hired to direct the Japanese sections of the movie, but he found out quickly that he had trouble working in a Hollywood and his obsessive attention to detail puzzled his American co-workers. He was let go after only a few weeks (his heavily re-written script was ultimately still used for the movie). In the 1970s, Kurosawa attempted suicide, but ultimately would fully recover. And by the time he made Ran, his eyesight had deteriorated so badly that in order to storyboard his films, Kurosawa painted brightly colored paintings depicting different scenes or images.

But with Ran, the theme of mortality reaches a powerful high point, punctuated by the tragedy surrounding the film. Takashi Shimura, a frequent collaborator on films such as Seven Samurai, Rashomon, and the aforementioned Ikiru, died in 1982. Fumio Yanoguchi, Kurosawa’s sound engineer since Stray Dog in 1949, died during the production of Ran. And Yoko Yaguchi, Kurosawa’s wife of thirty-nine years, also died during production. There’s a profound sense of closure to the film, as if Kurosawa took all the pain he endured in his life and used it to create this bleak yet beautiful film.

“To break a single arrow is easy. Not so, three in a bundle together.” – Hidetora Ichimonji

“You see father? Even in a bundle, three arrows can be broken.” – Saburu

Tatsuya Nakadai plays Lord Hidetora Ichimonji, an aging warlord who has lived a life of bloody conflict. Now, in his old age, wishes to live out the rest of his days in peace and impart some of his knowledge and fortune to his three sons: Taro, Jiro, and Saburo. Hidetora reveals that while he will retain the title of Great Lord, the role of leader of the Ichimonji clan will be given to Taro, the eldest child, who will also receive the prestigious First Castle. Jiro, the middle child, and Saburo, the youngest, will receive the Second and Third Castles respectively and will be expected to support Taro under any circumstance. Hidetora proceeds to give each son a single arrow and asks them to break the arrows in half. After each breaks their arrow, Hidetora then produces three arrows tied together and asks his sons to snap all three at once. Hidetora explains that while one arrow could be easily broken, three arrows bundled together could not. With Jiro and Saburo by Taro’s side, the Ichimonji clan can never be broken.

This arrow scene is a dramatization of a legend that dates to the 16th century. Feudal Lord Mori Montonari is said to have done this same arrow demonstration to his three sons, explaining that if they stick together, they cannot be defeated. But Kurosawa takes it one step further. Kurosawa asks a question that he will also come to answer in Ran: what happens if the bond between arrows is weak? After Taro and Jiro fail to snap the bundle of arrows, Saburo snaps the three arrows against his knee and proceeds to tell his father that his idea to divide power is absurd. “Father,” Saburo says, “what kind of world do we live in? A world barren of any loyalty, a world without any feeling.” Saburo continues by saying Hidetora has killed countless people and spilled unknown amounts of blood in his life, and showed no pity or mercy while doing it. “And we, your sons, we were weaned in battle, violence and chaos. And yet you count on us for fidelity and obedience, to protect you in your final years. And in my eyes, that’s enough to make you a fool. A senile, old fool.” While Taro and Jiro speak only words of flattery, Saburu’s words strike at Hidetora’s pride but comes from Saburo’s heart. Hidetora doesn’t see that, though, and bans Saburo, saying his ambition will soon grow too large and he will eventually turn against his family. He also bans Tango, one of his advisors, for coming to Saburo’s defense.

“You mean that I am to sit below you? Have you already forgotten who I am?” – Hidetora Ichimonji

Change comes hard for Hidetora. Here’s a man who has had others submit to him for so long that now having to submit to others comes as quite a shock. It all starts innocently enough. Hidetora’s concubines attempt to leave the castle only to be blocked by the arrival of Lady Kaede, Taro’s wife and the new lady of the castle. Lady Kaede uses her new authority to make Hidetora’s concubines step aside to allow her to step into the castle. Hidetora thinks this is unheard of, but is reminded that Taro and Lady Kaede are now the masters of the house and it is perfectly normal for the lady of the house to proceed first.

Things escalate when Hidetora kills one of Lord Taro’s men. Lord Taro had given the Ichimonji banner to Hidetora as a gift. But later, Lady Kaede “suggests” that Lord Taro ask for it back, much to the dismay of Hidetora’s men. This prompts Kyoami, the comic relief of the film, to come up with a joke at the new lord’s expense, likening him to a branch in the wind which “first likes to swing this way, then the like to sway that way. How the wind blows, nobody knows, underneath the sky, dangling high.” One of Jiro’s guards attempts to avenge his lord’s reputation by slaying Kyoami, but Hidetora kills the man by shooting him with an arrow. It’s an awesome moment.

This causes Lord Jiro to draft a pledge for Hidetora to sign, not only with his signature, but his blood as well. The pledge states that, first, Hidetora will relinquish the lands of Ichimonji to his son Taro, second, that Taro will be the sole ruler of the House of Ichimonji, and third, Hidetora will submit his authority to Taro, under penalty of punishment. Of course, Hidetora already declared everything in the pledge in the beginning of the film. But here, Jiro is flexing his newfound power, to see just how far he can go. Hidetora is being forced to sign a document which undermines his power, and this proves the greatest disrespect for Hidetora and he decides (after signing the pledge) to visit Jiro.

Things don’t go smoothly when he visits Jiro, either. After Hidetora catches Jiro in a lie, he leaves. But even then, away from his sons, he finds he can’t outrun the consequences of his actions. Lord Taro has given an order to the people under his rule to not give Hidetora or his men any food or shelter, or they will be put to death. His full force of his two son’s betrayals are fully revealed. At this moment, Hidetora realizes he has made a mistake. He can’t go back. And he can’t join Saburo, because after the way he treated his son, how could his son ever forgive him? Hidetora and his men go to the Third Castle and when he wakes up in the morning, he finds himself surrounded by armies led by his two sons. The battle is underway.

“The gods weep right along with us. They’ve seen us men on earth killing each other, killing again and again since the beginning of time. Only they can’t seem to save us from ourselves. Don’t cry. It’s how the world is made. Men prefer sorrow over joy. They’re forever seeking out suffering and rejecting peace.” – Tango

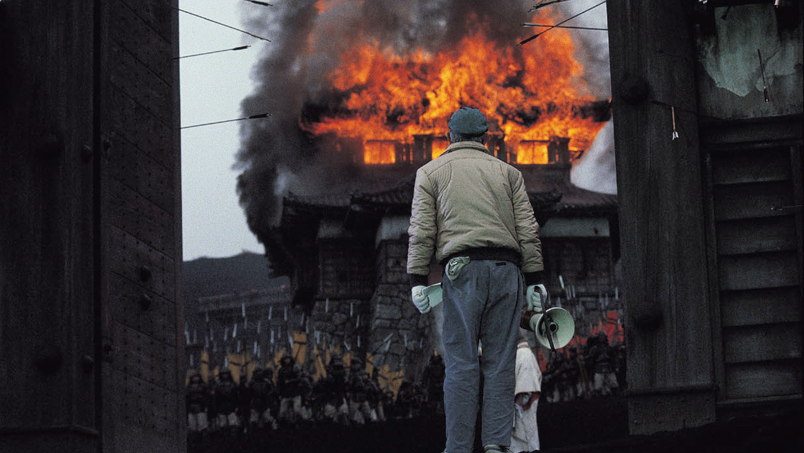

This battle sequence comes an hour into the film, and it’s mesmerizing. A chaotic battle sequence that is as beautiful as it is brutal, as dream-like as it is nightmarish. In a seven-minute sequence, Toru Takemitsu’s orchestral score is the only sound we hear as the siege commences. Waves of soldiers dressed in vibrant primary colors storm the castle from each side. Soldiers, their dead bodies riddled with arrows, litter the battlefield. Soldiers get blasted off their feet by the enemy’s muskets. One soldier sits in a corner and holds his severed, bloody arm. One soldier falls to the ground and immediately gets trampled by several horses. Inside the fort, Hidetora takes refuge, but cannot escape the chaos. Several of his concubines commit seppuku. Other concubines sacrifice themselves to save Hidetora from a line of musket fire. One by one, his trusted guards die trying to protect their Lord. Stranded at the top of the castle, Hidetora can only watch as everything burns down around him.

After seven minutes of continuous music, Takemitu’s haunting score, the score abruptly cuts out with our first sound of the battle – the gunshot that takes the life of Lord Taro. It’s a shocking moment and the sudden sounds of the battle are overwhelming. And finally, when the end is near, when the battle is over, Hidetora proceeds to commit seppuku, but he can’t find a weapon to do it. He has to live with his actions. Hidetora wanders out of the castle like a man in a trance. Dressed all in white, Hidetora resembles a ghost cursed to wonder the earth until the end of time.

“Forgive me. Forgive me.” – Hidetora Ichimonji

“Oh, at last. Now that he’s mad, he realizes his sins. The frightful vision I see floating in the void. All those that I destroyed. A phantom army is pursuing me. Ding dong goes the bell, that tolls in hell.” – Kyoami

The rest of the film sees Hidetora, now insane, go on a journey of self-reflection, wandering the lands that used to be under his control, encountering the ghosts of his past. One of those ghosts is Tsurumaru, Lady Sue’s brother, now blind and living in a small, dark shack in the middle of nowhere. But unlike his sister, Tsurumaru has not found peace with his past. He can never forget the pain. He says to Hidetora, “How could I ever forget the man who burned down our castle? The man who, in exchange for my life, gouged out my eyes?” Tsurumaru says he tried to be like his sister, to find forgiveness, and let the hate in his heart go away. In the end, Tsurumaru plays a song from his flute, a heartfelt gift of hospitality. The song has an incredible effect on Hidetora. It rises in pitch until it pierces his soul and ends up driving Hidetora back out into the wilderness.

“I don’t hate you. Everything was decided in our previous life.” – Lady Sue

“All I wanted was to avenge the destruction of my own family. I wanted to see this castle burn. And all that I set out to accomplish, I have done.” – Lady Kaede

Forgiveness and revenge. These two themes can be found everywhere in the film, but especially in the characters of Lady Sue and Lady Kaede. These two are very similar, sharing similar lives and similar deaths. They both have a violent history with Hidetora – he has killed their families and married them to his sons: Lady Kaede to Taro and Lady Sue to Jiro. They both have a long, painful history, but they dealt with that tragedy differently. Lady Sue turns to religion. Lady Kaede turns to revenge.

Lady Sue does not have a major role in the film. The biggest of her few scenes comes when Hidetora visits his “only remaining son” after being insulted by Lord Taro. He finds her praying. Hidetora has lived a life of violence and he knows he has destroyed many lives, Lady Sue among of them. He expects to be hated, and he even demands she hate him. But she doesn’t. She believes in the Buddha, and predestination. She gets caught up in the path of Hurricane Kaede, but she makes an interesting parallel to Lady Kaede.

While Hidetora wanders the land encountering the ghosts of his past, Lady Kaede manipulates events that will eventually topple the clan of Ichimonji. Kurosawa has depicted evil women before in his films like Asaji, Kurosawa’s version of Lady Macbeth, in Throne of Blood. But unlike Asaji, Lady Kaede is not affected by little things like blood and death. In one scene, she takes Jiro by surprise and overpowers him, grabbing his dagger and thrusting it against his neck, purposefully cutting him a few times, and as she straddles him, she gets him to admit he had his brother killed. After he admits his sin, she laughs mockingly at him then proceeds to seduce him by licking the blood off his neck and kissing him. Shockingly, it works. She gets him under her control. Once, when he tries to pull away, she cries and flails on the ground (while at the same time secretly crushing a bug that was crawling by her face – she’s Kurosawa’s ultimate female villain). And her death scene is an example of Kurosawa’s magnificent directing and as well as his incredible use of color.

“It grows so dark.” – Hidetora Ichimonji

We get another spectacular action sequence at the end of the film. It’s not quite the technical achievement that the earlier sequence is, but then again, it doesn’t have to be. The battle at the Third Castle represents the ultimate betrayal by Hidetora’s sons. Hidetora can only watch as his men die. That battle can be viewed from Hidetora’s point of view, an incredibly haunting look at death and betrayal and looming insanity. But the battle at the end of the film is just a battle. It feels very technical. There’s no point of view in that last battle, except for maybe the generals or the soldiers and for them, it’s just a battle.

As that battle goes on, Saburo is finally reunited with his father. It is the first time in a long time we see Hidetora happy. He smiles. He laughs. Hidetora says he and Saburo will have long talks together, “just father and son. That’s all I look forward to now.” But even this brief moment of happiness is cut short. A shot rings out and Saburo falls to the ground. He’s dead. And soon after, Hidetora collapses onto the body of his son, the weight of everything he has lived through – the violence, the death, the betrayal, and now the death of his son – finally taking its toll. Crying, Kyoami says, “Are there no gods anymore? Is there no Buddha? If you exist, why are you so mischievous and so cruel? Are you so bored up there? Must you step all over us and crush us like ants? Yes? Does it give you such pleasure to see a man cry?” But the question is, are the gods even listening?

“What a terrifying sky.” – Hidetora Ichimonji

Kurosawa often interrupts the action with sweeping shots of the sky, giving the film a very grand and terrifying scale. Kurosawa had always loved using nature to convey emotion or set the tone. Rain in Rashomon and Seven Samurai. Snow in Ikiru. Fog in Throne of Blood. Here, Kurosawa uses the sky to convey the sense of towering doom, of events throwing the universe out of balance. In the beginning of the film, as Hidetora unintentionally lays the plans for the chaos to come, the clouds above seem to swell and ripple out towards the frame, expanding at a terrifying rate that seems to prophesy oncoming horror. When the chaos and bloodshed starts, the sky resembles an apocalyptic painting. By the end, as the chaos dies down, the universe seems to be drifting by Hidetora. Whatever Hidetora may believe, Kurosawa gives the impression that the gods are present and are observing the events unfold.

Ran would not be Akira Kurosawa’s final movie. He would go on to direct three more movies. But he would never direct anything of this scale again. Kurosawa had a long, productive career, directing classic upon classic, and Ran is considered his final masterpiece (depending on your feelings on Dreams). Roger Ebert writes how Ran is as much about Kurosawa’s career as it is about Hidetora Ichimonji. Ebert ends his review by saying, “Ran is a great, glorious achievement. Kurosawa often must have associated himself with the old lord as he tried to put this film together, but in the end he has triumphed, and the image I have of him, at 75, is of three arrows bundled together.” I can’t imagine the problems Kurosawa faced during his life. But if this film is any indication, it takes a director who has battled through hard times to be able to create something so emotional. To be able to take the bleak with the beautiful. To create something that will be trancendent.