“Life is very big. And unknown.”

“Menstruation. Menstruation.”

(This piece contains SPOILERS for 20th Century Women, as well as for another film that I’ll mention when I get to it. I try to save all thoughts on Women‘s ending for one, specifically-marked section, but the rest of the film is fair game throughout.)

This is the third article I have written on the work of Mike Mills this year, following my looks at his advertising work and his other work up to Beginners. I hope you’ve enjoyed those pieces and I hope you enjoy this one, even if you didn’t find this to be the defining masterpiece of our time I’ve hyped it up as being. I will now explain in extreme detail why you are WRONG.

The Background

Mike Mills likes to take his time in preparing projects. Beginners came out in wide-release six years after Thumbsucker, and for the next four years after Beginners, there was not even an inkling of Mills making another film. But he did spend that time working on a script (and also raising a child, which I think is a perfectly fair reason to take it easy for a little bit). At one point it was named Oh Wow, Oh Wow, Oh Wow, after the last words of Steve Jobs (the development of Apple in 1979 California was at one point a part of the film), and it was a sprawling beast of a script eventually pruned down and given the greenlight by Megan Ellison (the only good billionaire)’s Annapurna Pictures in 2015, under the title 20th Century Women. The next year, when it was finished, it was picked up by indie distributor powerhouse A24 and given a premiere at the New York Film Festival and a plum December release date. But that date proved to be too late for A24 to build awards-season momentum, not helped by them having their hands full with Moonlight‘s Oscar campaign that year. And it didn’t have the box office to make up for that, coming and going out of theaters pretty quickly and eventually only receiving a nomination for Best Original Screenplay. I can’t really get a read on what its legacy will ultimately be due to how little time has passed since it failed to catch on (all I can say that with three members of my family, including me, loving it, it’s officially and forever a Narrator Family Favorite®).

I saw 20th Century Women for the first time on the first Saturday of its wide release. I loved it, said it was the best movie I saw from 2016, and then went on my merry way. But then a funny thing happened; this movie would not leave me. It consumed my thoughts for the next week in a way that literally no movie I’ve ever seen has done before. I went back to see it that Thursday, and that viewing convinced me that it was not just the best film made in 2016, it was the best film made since The Tree of Life in 2011. My opinion of it has only grown with further distance and viewings, and I am now confident that is one of my two favorite films of all time.

I hesitate to call 20th Century Women Mills’ magnum opus, because Mills is only 50 and still has plenty of time left to make even better films (even at his unfortunate “a movie every six years” speed). But goddamnit if this doesn’t feel like The One, the best film he will ever make and the one he’s been building towards with each successive project. Put it this way; this is Mills’ Tree of Life, and I would not be surprised if whatever he makes next feels like To the Wonder in comparison (I sure fucking hope it doesn’t, though).

The Basics

The “plot”, as foregrounded in the advertising, is of a single mother, Dorothea Fields (Annette Bening), enlisting a boarder in her house (Greta Gerwig) and their next-door neighbor (Elle Fanning) to help raise her son Jamie (Lucas Jade Zumann). But this is barely important, the very minimum amount of table-setting needed to give this movie an ostensible “center”. There’s a lot more than that around the center.

The Players

A point I kept hitting in my last Mike Mills piece was his boundless empathy for the people he filmed. No matter their surface ridiculousness or their small place in the scheme of things, Mills loves them and wants them to succeed. That empathy maybe reaches its peak here, a film whose essence can basically be boiled down to “five very nice people try to be nice to each other”. There’s no villain here, just people trying their best. They may have their foibles, and they may come into conflict with each other, but Mills is generous to each and every one.

JAMIE FIELDS (Born 1964)

Amusingly, the character who seems to demand the least sympathy in the film is the Mills surrogate, which is quite a ways from the approach in Beginners. Beginners was about many things, but it’s fundamentally anchored to the Mike Mills character, in perspective (his musings on time and his parents’ lives are what drive the whole structure of the film) and largely in screentime. The Mills character was even played by devilishly handsome movie star Ewan McGregor, to let you know that he really is important. There’s nothing wrong with this, especially when it’s handled as well as Beginners handles it, but that’s not what he does here.

Jamie is a character here, and certainly not a small one, but he is not cleanly the “lead” of the movie. He’s even played by a total newcomer in a main cast otherwise made up of indie stars or higher. But more than that, Mills shuts the viewer off to Jamie in many ways that prevents the focus from ever really fully reaching him. As a teenage boy, he frequently does stupid things, like knock himself unconscious for a prolonged period of time playing a dumb game, but he never really explains himself, despite his copious voice-over narration. In fact, that narration is largely used to share what the other characters have told him, making him almost more of a conduit for the other four than a character in his own right. Really, his role in the film is to be a sponge for the other characters, taking in their beliefs and personalities and trying to find a right balance between all of them. But if he could easily be a total cipher (or worse, a complete brat), Zumann invests Jamie with a tremendous amount of feeling, giving him an earnestness that makes even his worst moments not come off terribly.

DOROTHEA FIELDS (Born 1924)

If this movie has a lead, however, it is not Jamie, but Dorothea. Dorothea is a portrait of Mills’ mother Jan, previously embodied by Mary Page Keller in Beginners. But while it was a small part in a movie ostensibly all about the father (whereas here, we are specifically told “It’s always about the mother”), Beginners was haunted by Jan/Georgia. She is clearly as constrained as her husband (being married to a man who quite literally does not and will never love you will do that), and despite her valiant attempts to put on a brave face for Oliver, it seems all for show. All we really need to know about her is conveyed by how she reacts to Hal kissing her, her dutifully standing there for a few seconds afterwards, as if hoping for something more. We never really get to know her, and she’s obviously denied the late-in-life freedom granted to Hal. It’s a small tragedy amongst many in the film, but it lingers beyond its relatively short amount of screentime.

It’s only logical that Mills’ follow-up would give the mother more attention, but he goes the extra mile here in crafting a love letter to his mother. He’s said that his mother was much more active in raising him than his father, and so here, the father isn’t even given a small part, he’s flat-out not there. All we see of him is a distant reflection in sunglasses, and all we hear of him is his prowess at back-scratching. Mills has let this version of the mother be the (forgive me for unironically using this) strong, independent woman she might have been freed from her marriage. But taking away that baggage only reveals a heartbreaking truth about Dorothea/Jan; there is a piece of her that will never be fully-known, not even to her child, and she in turn will never fully know her child. They even get almost identical lines of narration trying in vain to understand how they both grew up. Jamie says of Dorothea, “When she was my age, people drove in sad cars to sad houses, with no money or food or televisions. But the people were real.” And then Dorothea says of Jamie, “He grew up with a meaningless war, with protests, with Nixon, with nice cars and nice houses, computers, drugs, boredom.” They both narrow each other down to simple ideas and simple images, and both are off-the-mark in anything more than the broadest view of each other. But the difference is Dorothea at least has the sense to follow that with “I know him less every day.” Jamie tragically does not have the self-awareness to know how little he really knows his mother, at least in the moment. The most wrenching demonstration of that is him reading aloud from an essay about the pains of being a middle-aged, sexual woman, clearly believing this to be a complete picture of Dorothea, and Dorothea reacting with a disguised hurt at her son getting her so wrong. At least she’s not there for his other misinterpretations.

Dorothea grew up during the Depression. We know this because Jamie likes to mention this whenever explaining away her eccentricities. This is his shorthand to understanding her, writing off her quirks with “it was a different time”. But, of course, no one can really be narrowed down to a clean representation of when they grew up, as he should know, being as much a product of his mother’s 40s upbringing as he is of the 70s. And Dorothea seems infested by some of the 70s spirit as well, showcasing a casual bohemianism and openness to the new (just look at how earnestly she tries to understand and analyze the appeal of Black Flag). Really, Jamie inadvertently sums up his mom better with two lines of his narration; “She smokes Salems because they’re healthier. She wears Birkenstocks because she’s contemporary.” Therein lies the fundamental conflict of Dorothea; she’s still tied to the past, but damnit if she isn’t trying to keep up with the present too.

About the Salems. They seem to just be a running joke for the film’s first half, with a cigarette practically hot-glued between Dorothea’s fingers, if not her lips, in every scene, and her even getting to explain that when she started smoking, they weren’t bad for you, they were just hip. And then a turn happens, a turn that the movie hinges on (it neatly separates the first and second halves of the film, coming at almost exactly the hour mark in a film that runs 1 hour and 59 minutes), where Dorothea delivers the following line of narration:

It’s 1979, I’m 55 years old, and in 1999, I will die of cancer from the smoking.

This comes out of nowhere, and is a gut-punch for the ages (the bluntness of “from the smoking” is a nail directly in the heart). It also puts all that previous smoking in a totally different context, with what were previously amusing little moments coalescing into a much grander tragedy (I’ll talk more about the film’s relationship to the moment later in this piece). But maybe as important is what comes immediately before and after that revelation. Before, Dorothea is talking about Jamie’s relationship to punk as only a slightly clueless mother could, in awe of and slightly worried by these raucous people influencing her son. But after it is established her narration is from beyond the grave, she leaves behind her earthly blind spots and speaks of punk’s coming death at the hands of Reagan. This is a Dorothea we don’t see in the film, one with a totally rounded perspective on the world that she could not have possible had on Earth. So now every following scene with her is suffused with two tragedies; one being her eventual death, and the other being that it was only death that could get her fully out of her bubble.

Moving all that stuff aside, it’s almost impossible to exaggerate how good Annette Bening is in this movie. She does with microexpressions here what most actors can’t even accomplish with bombastic monologues. Looking at the scene where Jamie reads her that essay, the way she has to go from sadness that her son has gotten her so wrong to acting impressed at him for finding and reading it in the first place once he looks up at her, and then back to sadness, is a jaw-dropping display of maximum emotional impact in minimum gestures. And towards the end, in a potentially standard-issue reconciliation scene between her and Jamie, she finds untold depth of feeling in one steady smile, underplaying this massive emotional moment to perfection. Her restraint here also gets played for some fantastic comedy, including her reaction to Jamie getting in a fight over “clitoral stimulation” (“Kid, I’m sure you will!” is a line delivery for the ages) and when she tries to sneak a cigarette during a bit of meditation (just the way she shuts her eyes after fetching and lighting the cigarette is screamingly funny). That Bening was not nominated for an Oscar for this is a bigger travesty than whatever Oscar snub you’re thinking of right now.

ABBIE PORTER (Born 1955)

One of the biggest changes from Mills’ life to its on-screen depiction in both this and Beginners is him being an only child in the films. In real life, Mills was the youngest of three children, and the only boy of the three (they caught onto their dad’s homosexuality much earlier and told Mike about it). And those sisters (with a special emphasis on oldest sister Meg Mills) are combined to form Abbie Porter, a photographer and artist living out of the Fields’ house. Abbie’s backstory is Meg’s, from her leaving California to go to New York (the same path for Gerwig, Mills, and the later protagonist of Gerwig’s Lady Bird), her coming back after she gets cervical cancer as a result of her mother taking fertility drugs, and her job as an underground photographer and intermediary between the punk scene and the Mills/Fields household.

It would be easy to play Abbie as a Stoic Survivor, a Manic Pixie Dream Girl who gifts Jamie with culture, or a cartoon punk, but Gerwig here makes her something deeply human. As the movie starts, she is distraught over having to wait for a new round of tests to see if her cancer has returned, her eyes wide-open and watery, but at the same time, she demonstrates a curious hardness and perseverance, because she has her camera in hand, and she can turn her pain into art. She has that same demeanor and look a little later when she’s explaining a new art idea, where she photographs all of the objects she owns, but those tears are clearly tears of joy, joy at the fact that she’s created anything at all, let alone something from the depths of the worst experience of her life. Her quietly impassioned delivery of “Can I show you?” says more about the wonder of creating than just about any other movie about artists.

This is an astonishingly controlled performance from Gerwig, someone who before this had played so many characters with the habit of spilling themselves out for all to see (and those are fantastic performances too, don’t get me wrong). Frances Ha and Mistress America‘s Brooke Cardinas are continually bubbling over, but Abbie keeps a tight lid, and that makes the little bits of what does come out all the more wrenching (and occasionally comedic, as in her wonderful screaming of “I don’t like you!”). When she’s getting the news of having an “incompetent cervix”, she breaks down off-screen, the viewer left with one image of her collected and one of her already crying (much the same thing happens later, when a piece of advice from Dorothea instantly turns her from anxious to moved). And when Jamie innocently asks her how she’s doing at one point, Gerwig freezes her previously inviting expression and you can practically see a switch moving behind her eyes as she now has to deal with what’s happened to her.

JULIE HAMLIN (Born 1962)

Julie is a composite character, a reflection of all the teenage girls who came into Mills’ life, were friends with him, and even slept in his bed (don’t worry, nothing happened). This could potentially lead to her being more thinly-drawn than her more directly-inspired fellow characters (although Mills builds in a critique of that, with her telling Jamie at one point “That’s your version of me, that’s not me”), but Mills ably avoids that trap.

Julie’s mother is a therapist, and therapist-speak slips out of her almost second-nature in between her typical teenage showings of rebellion (few other teenagers are going around talking about a baby’s “growth personality”, and maybe equally few adults too). She can go from giving the biggest, goofiest smile at the suggestion that she “does it” to psychoanalyzing Dorothea as “compensating for her loneliness” in no time. And even following a traumatic sexual experience, where some meathead came inside her despite promising not to, she’ll still try a bit of therapeutic roleplay where Jamie shares his (comparatively minor) problems with his mom to her. In that scene, she’s more than a bit like Abbie, displaying a calm professionalism despite the tears streaking down her face (to make the point clearer, Mills follows that scene of roleplay with Abbie indulging in a bit of roleplay herself). And yet she still resents Abbie, and any therapist worth their weight in salt could tell you why; Abbie is a genuine free spirit, and Julie is rebelling more out of conformism than she is fighting against it. She’s simply doing what teenagers seem to do, getting stoned and having sex, without any real involvement in what she’s doing. She asserts her agency (when Abbie takes a picture of her as part of a project where she photographs everything that happens to her in a day, Julie shoots back “I didn’t happen to you”), but her mother would be quick to shut down that notion.

Her friendship with Jamie is seemingly her one beacon for just behaving like she really is, not like she’s trying to be. Despite Abbie’s protests about Jamie letting her sleep in his bed and not sleeping with her, their relationship is healthy for the both of them, with Jamie at one point helping her get a pregnancy test following that bit of bad sex and she returning the favor by teaching him about her sexual experiences (half the time she regrets it, but she keeps doing it, in a wistful line delivery for the ages, “because half the time I don’t regret it”) and even how to do a cool-looking walk while smoking. The loveliness of their friendship only makes it sting more when Jamie finally heeds Abbie’s advice and takes Julie for an excruciating hotel room rendezvous. There, she puts her therapist-senses to best use, because she sees straight through Jamie’s attempts to rationalize what he’s doing and sees a dumb, horny teenage boy, just like the others.

Fanning is one of the best actresses currently working in any age range (and Paul Thomas Anderson agrees, so you know I’m right) and this is her very best performance to date. She has one of the most magnetic stares in the business (just look at The Neon Demon, released the same year as this), and that stare is put to great use here, as she’s always sizing up her surroundings and seeing what weaknesses she can point out. Her best use of that comes in her big scene with Bening/Dorothea, in which she effortlessly goes toe-to-toe with Dorothea over her bad luck with men since her divorce, and in between puffs on a cigarette, no less. But despite all that hardness, Julie is still a teenager, and Fanning plays her lapses into the teenager mode both so wonderfully (I’m given life just by her big smiles whenever she engages Jamie about her alleged life of debauchery) and so devastatingly.

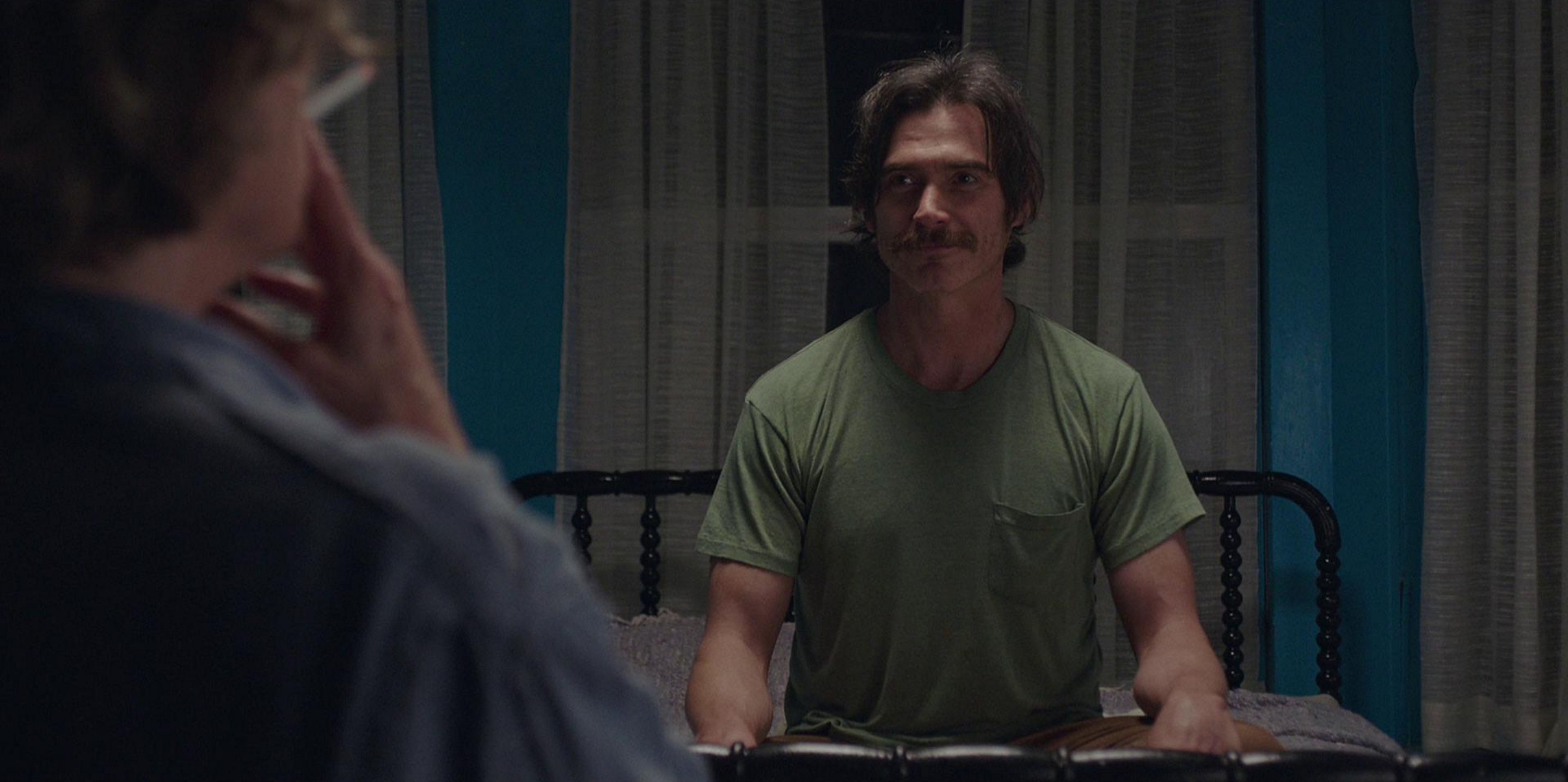

WILLIAM

Nope, no last name or birth year. William (played by Billy Crudup) is the one purely-invented character in the film (or at least I haven’t heard Mills talk about an inspiration for him), and Mills has said he created William as the male version of a common type of female character in male-led movies, that of the sex object getting passed around. If Mills was, say, Paul Feig, he might leave William as some dim-bulb eye candy and have that be the joke. But Mills is not one to underserve a character just to score some cheap laughs or progressive points.

Of the film’s central pentagon, William is by far the most mysterious character, eluding some kind of concrete judgment. As the film opens, he seems easy enough to pin down; he’s the comic relief (although, as Dorothea notes, “You don’t have many funny lines, do you?”), a hippie handyman fixing up the house and babbling about souls being born in the dirt to an amused Abbie (who also replies to the revelation of him making his own shampoo with a priceless “Of course you do”). His stache and hair are even styled exactly like that other hippieish 70s Crudup character, Russell Hammond (although Mills doesn’t seem to care that much for Almost Famous based on this Uproxx interview). But then comes a scene with Abbie and William doing a little role-playing game. It starts off with William dutifully going along with Abbie’s prompt (he’s a professional photographer, she’s his unwitting subject who he has the hots for), and then when he comes in close, he whispers, with all the tenderness in the world, “I’m sorry. I’m really sorry”. This isn’t some dope to laugh at, but someone with a surprising reservoir of humanity.

Not that he isn’t funny. Indeed, he’s the funniest part of the film’s centerpiece scene, the dinner table chat about menstruation, in which he gives Jamie the advice to “never have sex with just the vagina, you gotta have sex with the whole woman” (a Crudup improv) and spoiling One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest for Julie, who missed the end when she had her first period (I aspire to the Zen calm he shows while describing “the big Indian” smothering Jack Nicholson so he could be free). But Mills never fully gives into making William a purely funny creation, with even his odd moments having surprising power. In one scene, he reads a passage from Our Bodies Ourselves and, after the passage ends in a list that trails off into ellipses, says of the ellipses “to me that means, ‘and what else?'”. It’s strange and at least a little simplistic, but also weirdly profound.

Later in the film, William is deepened with his own montage, where Dorothea relays us his backstory and we learn just how wrong our first impressions of him were. He really isn’t a hippie at all, staying with them for a time but never really connecting with them (“they made him feel old, and uneducated, and poor,” as Dorothea says). And yet he finds himself struggling to detach from that lifestyle all the same, aimlessly moving from partner to partner in his own little, quietly depressing version of the Summer of Love. He almost functions as Julie’s Ghost of Christmas Future, showing the long-term emotional costs of throwing yourself headfirst into the counterculture more out of obligation than anything. It’s a depressing life, but with one saving grace; his pottery, which he throws his heart and soul into just as Abbie does with her photography (the most sensual shots in the film are the close-ups of Crudup’s hands, worn but gentle, and capable of creating beautiful things).

Crudup was sort of pushed as a leading man in the early 2000s, but he always seems more comfortable in supporting parts, and this is one of his very best in that category. He never tries to overshadow his costars (even his insights during the dinner party are presented unshowily and straight-down-the-middle), giving a performance that it almost requires a second viewing to fully notice and pay attention to (I personally didn’t even catch his line about the ellipses until the second viewing). He treats both his laugh lines and his big emotional moments like they’re no big deal, perfectly fitting his character’s perpetual nonchalance while still making a massive, if quiet, impact.

SANTA BARBARA, 1979.

or:

Life Out Of Balance

And what about the place where all these people are joined? Compared to Beginners‘ hopping around, we at least know precisely where and when we are, because over the first shot, we see “SANTA BARBARA, 1979.” over a beautiful shot of the peacefully churning ocean. That peace will prove to not be representative of this time and place, though.

Really, the feeling of Santa Barbara, 1979 by the people living through it is best described through the house the five main characters are staying in. It’s a house full of history, having fallen into disrepair after World War II and subsequently being purchased by 60s bohemians, and it’s a beautiful house, marked with walls of vivid red, yellow, and green. But it is always under repair, never finished or even seeming to get close to being finished. It’s a place continually in flux, and so, it seems, is Santa Barbara, marked by the uneasy ongoing dialogue between suburban domesticity and the growing punk scene (Mills previously explored a similar dynamic of suburban conservatism vs. confrontational art in his documentary short Deformer). And things are only going to get more uneasy from here.

After some gorgeous Santa Barbara establishing shots, Mills cuts to… a car ablaze. And it’s not just any car; Dorothea explains in voice-over that it’s the car they drove Jamie home from the hospital in after he was born. It’s a small piece of history, sure, but it’s still history and a connection to the past lost (and Mills has, in interviews, also connected it to the death of the motor industry, making the loss of the past with it burning all the more explicit), a tiny tragedy to start a film that eventually moves onto bigger ones. And there are plenty of those occurring at this time. As Jimmy Carter sez in the “crisis of confidence” speech replayed in the film, “we are at a turning point,” but even he can’t quite imagine the extent of the turning point coming. As Dorothea tells us, Reagan is coming, and with him AIDS and a less quantifiable moral rot, the death of punk is looming, and not even skateboard tricks will remain the same.

Perhaps the film’s boldest scene comes when the characters all listen to that Jimmy Carter speech, in which he talks of a country increasingly adrift. Of course it speaks to the characters, who at that point in the film (roughly the beginning of the “third act”) are drifting even from each other. Mills’ empathy shines through here in how he reconnects them through their shared isolation, with a montage linking them by first showing them each performing tasks alone and then eventually connecting them through shared actions (we first see Julie smoking, then Dorothea smoking; then Jamie in bed, followed by Dorothea in bed). But much more ballsy than that is what comes before; Mills throws in footage from Godfrey Reggio’s Koyaanisqatsi, perhaps one of the definitive cinematic documents of a modern world led astray. As Reggio’s sped-up footage of anonymous masses shopping and driving and seeking pleasure plays over Carter talking gravely of an increasingly material-minded nation, we realize that these five people we’ve been following are the furthest thing from alone, that their ennui is the ennui of everyone around them. Mills makes the connection even clearer by shooting the character-centered montage in fast-motion, having them speed through the motions just as Reggio’s subjects did. Mills has tied his characters and subjects to larger cultural moments in many of his other works, like six paperboys in one small town representing the modern state of their profession in Paperboys, or Mills’ father being merely one piece of the struggle for gay rights in Beginners. But this gambit goes far beyond those, making these characters stand-ins for everyone. And it works! Partially that’s because it comes relatively late in the film, with Mills allowing you to develop an organic relationship with each character, so that their struggle, and in turn the United States’ struggle, actually means something, like the “Wise Up” singalong in Magnolia if the entire population of California was joining in on it. Maybe it’s because I’ve only seen this movie in the wake of an incredibly tumultuous time in American history (I even saw it the first time the day of the Women’s March), and have that extra connection to its findings about an increasingly fractured America. Or maybe it’s just mostly the combination of visuals and audio (both Carter’s speech and Roger Neill’s incredible piece of score for it, posted below). Whatever it is, it is a direct hit to the gut.

The Aesthetics of Memory

Almost all of what Mills made up to Thumbsucker was very obviously the work of a man with a recognizable aesthetic, one built around natural lighting, very fussed-over compositions (even in documentaries), and frequent pans. The problem is that that aesthetic proved to be stultifying over Thumbsucker‘s 90 minutes, so he wisely went back to the drawing board for Beginners. He still relied on natural lighting there, but his compositions were looser (most notably in the unfussy, handheld images of the section with McGregor and Melanie Laurent) and he eliminated the pans altogether, mostly shooting in simple tableaux. With his stylistic restrictions there having paid off, he goes back to a more noticeable style here, but his approach here combines the best of both of his previous styles. He’s once again using natural lighting, but whereas his last two films reveled in the murkiness that often results from that approach, this looks as lush as any studio production. Shot by Sean Porter, who shot the murky, shadow-laden Green Room the same year as this, this film is constantly watched over by California sunshine, and even interiors are never anything but warmly inviting. Mills says in the audio commentary that he and Porter were inspired by Gordon Willis (particularly his use of single-source, curved lighting), but unlike pretty much every other Willis imitation, there’s barely any darkness to be had, and even a scene of Abbie and Jamie shot in total darkness draws the viewer’s attention to the flash of Abbie’s camera rather than the black surrounding them (the one exception is the dim, ominous images of Julie’s disastrous bit of car sex, which look like they could have come from It Follows). Porter and Mills seem most inspired by Willis’s work on Broadway Danny Rose, where classical, high-key imagery always casts a flattering light on its lovable misfit characters.

In many ways, this is Mills’ most stylized movie to date, but unlike in Thumbsucker, the style feels like a natural extension of the film’s approach as a whole. This is a memory-film, and every oddball technique he uses is in there to capture the feeling of a memory. The most prevalent are his camera movements, which are almost never motivated by what’s occurring on-screen. Instead, Mills will dolly in and out of static scenes, occasionally even pushing in and out of door frames. These movements serve as a genius representation of how one tries to process the exact geography of a memory. The mental eye will never produce a clear picture of where everything/one is in a memory, and so neither will the camera, as it never settles on one spot to view scenes from.

There are even more noticeable examples of this throughout. Several scenes are shot with the image blurring and fringing, moving objects leaving behind a rainbow streaking (Mills has admitted that he stole this idea from Daisies). This is done with scenes in cars, with Mills transcribing the youthful exuberance of driving to L.A. for a show or speeding down the coast with your girlfriend, or the frantic worry of speeding down the coast in search of your son, into visuals, making the car an object of almost mythic importance, capable of transcending the boundaries of time and space. It probably shouldn’t work, but goddamnit, it does. And even more unlikely to work is Mills’ use of fast-motion. Obviously, it’s there to tie into the visuals of Koyaanisqatsi in that one sequence, but it’s also a representation of the mind’s fuzzy grasp of how time in memories works. The brain can’t keep a concrete timeline straight, so of course some memories would look like Benny Hill when translated visually, especially a traumatic one like an early scene with Jamie knocking himself unconscious in a dumb game (there, you almost don’t notice the fast-motion for most of it, which makes the moment is becomes obvious all the more unsettling, and fitting to an unsettling scene).

And then there’s the score, by Roger Neill (one of three credited composers on Beginners). It’s an entirely synth-based score, directly inspired by the work of Brian Eno (who had a hand in at least four songs on the soundtrack). But the sound of it is that of someone trying to remember a Brian Eno song, with a waviness and etherealness in the sound that stands in for the “distortion” of memory, or maybe it’s the musical equivalent of those dissolves that usually accompany flashbacks to memories (the end result actually sounds like a non-Eno song in the film, the hazy synth-punk of Suicide’s “Cheree”).

While this film shares a lot with Beginners in its editing style, throwing in montages that cut between narrative footage, historical photos, and artful tableaux of objects, Beginners kept up the montage style throughout its two timelines, while this lets its individual scenes breathe. Both are about moments reflected in the grander scheme of life, but while Beginners seemed more interested in the larger picture, this strikes just the right balance between the two. One is not subservient to the other, but instead they complement and inform each other. This is the most Malickian part of the film, so it’s no wonder it’s edited by Leslie Jones (no, not that Leslie Jones), who edited The Thin Red Line (she’s also an expert in combining protracted real-time with surprising interruptions and ellipses, with her work on Paul Thomas Anderson’s Punch-Drunk Love, The Master, and Inherent Vice). As in Line, scenes played out in full are accompanied by lyrical, time-hopping montages, and the viewer is asked to consider them as two equal pieces of one picture. But here, the scenes that play out often seem completely inconsequential in the moment, and the viewer is asked to put in the work to view these moments as grandly as they do the large-scale montages. This is the cinematic equivalent of Abbie’s art project photographing what happens to her; the things she and Mills are cataloging may seem to have no obvious power, but viewing them as a whole reveals just how powerful they are. I’ll put it another way; the kindest thing Abbie does to Dorothea is give her a picture of Jamie from when they were out at a club. It’s not a remarkable picture, but it means everything in the world because it follows Dorothea telling Abbie, “You get to see him out in the world, I never will”, and finally gives Dorothea that kind of exposure to her son she’s previously been denied. Mills is the Abbie to our Dorothea, gifting us with moments that are so much more meaningful than they may first appear.

BUZZCOCKS MEETS BOGART

– The sticker on the film’s soundtrack

Mills sums up the film’s approach by saying it’s a dialogue between two songs; Rudy Vallee’s version of “As Time Goes By” and the Buzzcocks’ “Why Can’t I Touch It?”. On the surface, this sounds like it’s simply talking about the generation gap between Dorothea (the Bogart worshipper) and Jamie (the punk enthusiast). But listening to the songs reveals that it’s actually a microcosm for the film’s approach to time and the tiny moments therein.

“As Time Goes By” takes place entirely in the macro, viewing time from a far enough distance that it sums up the entirety of humanity as simply “a fight for love and glory” and speaks with authority on a kiss just being a kiss in the grand scheme of things. It’s a reassuring message to those weary of modern society from someone omniscient, maybe someone who even views the world in Mills’ time-jumping montages. The Buzzcocks, meanwhile, take the role of the modern folk being addressed by “As Time Goes By”, the people still trapped in 1979, who find that all that knowledge means nothing to them right now. “Why Can’t I Touch It?” is a completely present-tense narrative, stuck in a moment of frustration where you desperately want a connection to something that you can’t access, no matter how real it seems (if Jamie would stop thinking he knows his mother so well, he might realize how much this song applies to him and his efforts to analyze her). These are complements to each other, not generic opposites, and each ones has its own virtues and importance.

“All of My Objects”

– Track 10 on the soundtrack

In his nonfiction work (as I explored in riveting detail), Mills was fascinated by the idea of presenting a person’s possessions and interests as a way of getting to know them, where a “Stone Cold” Steve Austin cut-out in the corner of someone’s room is as powerful a detail as anything they could reveal in an interview. This was largely unused in Thumbsucker, and Beginners had some of it, but 20th Century Women is the first of Mills’ features to really go all-in on it. A recurring thread throughout the film reveals how various kinds of art have shaped its characters, and how they carry that with them in their daily lives.

Most prominent is Jamie’s various reactions to the feminist literature he’s given by Abbie. At first, this is presented comically, as when Jamie parrots back talk about “clitoral stimulation” to an unresponsive skateboard knucklehead (this dipshit saying that he stimulates his girlfriend’s clitoris “with my dick” is next-level comedy), or when he recites Abbie-approved statements about how “pretty music is used to hide how unfair and corrupt society is” and “age is a bourgeois construct”. But it becomes less funny when he reads that essay to Dorothea, and it sounds becomes clear that Jamie is, while well-meaning, ultimately more than a little clueless about what he’s reading. When Julie tells him off later about being just like the other jerk-off guys, only with the added veil of feminism, it hurts because it really does ring true.

But every character carries with them a token of pop culture, one which has substantially shifted how they live their lives. Abbie is the most notable one, with her flashback montage telling us that she dyed her hair red after seeing The Man Who Fell to Earth, and modeled herself on the fierce, unconventional women of the New York punk scene (including Siouxsie Sioux, whose “Love in a Void” seems to inspire her project of taking photos of all her objects against a white void, and which she plays while taking the photos). She even delivers a breathless, on-the-spot monologue about the virtues of The Raincoats to Dorothea at one point. But Dorothea does this too, taking on Humphrey Bogart’s demeanor and rhythms, watching Casablanca on TV with Jamie, and even making promises to Jamie about marrying Bogart in the next life. And Julie tries to understand herself better by throwing herself into Judy Blume’s Forever and Susan Lydon’s The Politics of Orgasm.

The Dancing

But no form of entertainment is more beautifully-used as a tool of expression in this film than dancing. Dancing is perhaps the lynchpin of so much of what this movie is trying to say; it’s a purely communal and universal artform, capable of connecting those from different times or backgrounds… but only for a brief moment. Still, what moments are the dancing scenes in this movie.

Mills has said that he took inspiration for the dancing scenes from Italian director Ermanno Olmi, particularly his I Fidanzati, which opens in a dance hall and focuses on the random inhabitants of it for a lengthy period before the two main characters even enter. There, dancing is an all-purpose healer, reminding the leads of the wonderful times they spent together before the male goes off to Sicily for a job, and just generally providing entertainment for all the people surrounding them. Here, Mills gives us even more ways dancing can mend us and the characters in front of us. Sometimes, it’s romantic, as in the swooning slow-dance Dorothea and William have in a seedy bar at one point. Sometimes, it’s purely personal, as in Abbie’s introduction, where she stress-dances to Talking Heads’ “Don’t Worry About the Government”; we’re later told that part of what she learned in New York was to “dance whenever she felt sad”. But the most powerful examples are the ones that join together the characters. The funniest and sweetest of them is Dorothea and William trying to dance to Black Flag (you haven’t lived until you’ve seen Annette Bening try to headbang) and Talking Heads, where them dancing together to “The Big Country” is simultaneously them becoming closer to each other, them becoming more connected to the zeitgeist, and them understanding Jamie a little more. Jamie also becomes closer to Abbie through dancing, with her teaching him how to dance to punk coinciding with her telling him her life story (and she later pushes him through the rituals of “verbally seducing women” while they dance). But the best scene of this nature comes even later, and leads us to…

The Ending

(Yes, there are SPOILERS in this section.)

This movie would likely be a complete mess if it didn’t stick the landing, and by god, does it. We’ve been told about the forward marching of time and even how Dorothea will die in voice-over, and yet all that doesn’t quite prepare us for the power of the home stretch. The final scene we get with all five of the leads together sees them packed in a hotel room and eventually slow-dancing together, switching partners with an ease that drives home just how intimately connected they all are. It works so well as a mini-thesis statement (so much so that it’s surprising that it wasn’t the scripted ending and was thought up in rehearsals) that it’s almost surprising the movie keeps going for a bit after that.

Following that, we get a final stretch with Dorothea and Jamie, made up entirely of beautiful bonding moments between the two occurring in the least likely places imaginable; in a nondescript Mexican restaurant, in the aisle of a supermarket, and finally back in the empty hotel room, while Jamie is bleaching his hair. And it all builds up to the image of mother and child connected and the generation gap bridged on the California road, with Jamie skateboarding alongside Dorothea as she drives. It’s a beautiful moment, but as with so many other scenes in the film, it is a moment whose time will eventually pass. As they do this, the sun is setting and Jamie’s voice-over tells us that this was little more than a brief detour in their relationship, and they never really grew any closer or learned anymore about each other following this. But also like so many other moments in this movie, its beauty lasts long beyond its time on-screen and even its actual impact in their lives.

And I haven’t even gotten to the real emotional haymaker of the ending yet. Also in the aforementioned Uproxx interview, Mills talks about the kind of ending where you find out what happened to the characters after the events of the movie (he specifically mentions Animal House) as “such a Hollywood convention and I kind of adore that.” That kind of earnest appreciation for this trope takes what could’ve been a lame gambit into something deeply devastating. Just the things we’re told the characters will do are enough to get the waterworks going (I’m honestly finding myself getting emotional just typing these things out); they will all break apart within a year of the film’s end, Julie will lose contact with Dorothea and Jamie and never talk to her mother again, Dorothea’s handwriting will be so illegible as she’s dying that her instructions to Jamie about her stocks will be inscrutable, William will keep changing partners for the near-future, and, most moving of all, Abbie will go against her doctor and have two children (that’s also from Meg Mills’ biography). But what really knocks this out of the park are the filmmaking decisions around the reveals. For one, after the entire film was narrated by either Dorothea or Jamie, the other characters are finally allowed to describe their fates for themselves, suggesting lives for them even bigger than we were allowed to see this whole time. And then there are specific shots that stick in the mind. There’s the final shot of Julie’s mother (there’s no more pure example of Mills’ empathy than him giving an emotional farewell moment to a totally minor character), with the camera pushing out from her and leaving her behind in the therapy room just as Julie is leaving her behind. There’s the moment where Dorothea’s favorite aspect of her husband, his back-scratching while she did the stocks, is recreated with William in the husband’s place. And there’s Julie staring down the camera as she gives her last bit of voice-over, looking out to the world ahead of her.

And the fast-motion is never more astonishingly-used than here. Here, the brain’s fickle grasp on time becomes actively traumatic when it rips these characters apart from each other with heartbreaking speed, taking apart in three seconds what was built in two hours (Julie rushing out of bed with Jamie and out the window hurts like no tearful goodbye scene ever could).

By the end, we are left with Dorothea and Jamie once again. The image is one of pure bliss for Dorothea; she is getting to fly a plane, having tried and failed to become a pilot during World War II, and Mills’ camera patiently observes her over the ocean. The voice-over is something much more poignant; Jamie will have a son (just as Mills did in between Beginners and this), and this is what he has to say about that; “I will try to explain to him what his grandmother was like. But it will be impossible.” And so Dorothea will remain an enigma for all time. But Mills is too generous to send her off like that, so instead, the final audio he plays over her is “As Time Goes By”, finally granting her wish to be Bogart. If he couldn’t ever quite figure out who she was, the least he can do is make her who she wanted to be.

I’m not crying, you’re crying.

(End SPOILERS)

POSTSCRIPT: 20th Century Women and Lady Bird

Before anyone replies with the obvious gif in response this section, I’ll beat you to the punch.

With that out of the way, I can now explain why this isn’t slightly off-topic.

I may be unsure of what exactly 20th Century Women‘s legacy will be, but I can say now that it is guaranteed a small spot in film history just on the basis of Lady Bird. Gerwig’s solo directorial debut, also released by A24, has garnered the massive critical and popular acclaim that seemed to partially elude Women (and it will almost certainly get more awards attention), but it’s almost more rewarding viewed as a dialogue with Women. Gerwig has talked about Mills’ influence in the film’s on-set environment (she took from him the idea to give all the cast and crew members nametags), and some parallels are clear enough at first blush; it being the story of a mother and a child, set in a turbulent time of recent American history, and where a character (in this case the semi-Gerwig surrogate Christine “Lady Bird” McPherson, played by Saoirse Ronan) makes the pilgrimage from California to New York. They also share production designer Chris Jones (who gives the locations, from Lady’s Bird house and high school to the ritzier houses she wishes she lived in, the same surprising candy colors as Women‘s main house), and it even uses Mills’ trick of making the dates not quite line up with the actual autobiography (Jamie is two years older than Mills was in 1979, and Lady Bird graduates high school a year later than Gerwig did). But it goes much deeper than that.

While Lady Bird is far more rooted in the POV of its lead than Women was (and in turn rooted in the moment, with the world outside barely acknowledged outside of brief TV reports about the Iraq War), it shares Women‘s undying empathy for every flawed, beautiful character in its world. The most striking example is the small character of Father Leviatch (Stephen McKinley Henderson), who in maybe five minutes of screentime develops a character with enough quiet tragedy (some of which is rumored by Lady Bird’s classmates, but the rest of which is merely suggested by Henderson’s performance) to fill an entire other film. The characters who would seem most likely to be one-dimensional foils for the main character, namely Kyle, her pretentious second boyfriend, and Jenna, the popular girl she befriends at the expense of her best friend, are given life beyond their constricting labels. Kyle may be laughable in his alleged “anarchism” (he exists on a “bartering system”) and liberal use of “hella tight”, but he’s got real pain, pressured by his dad to attend his Catholic high school, the same dad who is seen asleep in his chair, wasting away from cancer (the shooting script goes even further with this, preceding Lady Bird getting an exciting bit of mail with her reading an obituary for the father). He looks and feels like a soured version of Jamie, right down to the absence of any female figures in his life. And Jenna is never as vapid or dumb as she would probably be in any movie, spending her time with Lady Bird mostly talking earnestly about her future and even her falling out with Lady Bird being totally reasonable in light of Lady Bird’s lies about herself.

But as with Women, its center is its mother-child relationship, and the difficulties that come with it. Like Jamie, Lady Bird likes to pretend that she knows her mother, but her explanations for the mother’s behavior are even more confounding. Whenever she’s with someone else, she’s quick to leap to her mother’s defense, asserting that she has a good heart no matter how outwardly scary she appears. But once she’s at her house, that goodwill instantly curdles and she starts talking about how much she hates her mother and how much her mother hates her. But it’s maybe understandable, because Marion McPherson (Laurie Metcalf) is an even harder person to get a hold on than Dorothea. She loves her daughter, but hers is a love that keeps coming out as bile and criticism. And yet she shares Dorothea’s love for others, caring for Father Leviatch in his time of need, giving a coworker a gift for his newborn baby, and even excitedly chatting up a saleswoman at the thrift store about her toddler. It’s one thing to not know your mother, it’s another to feel like everyone else knows her better.

There’s also hints of Women‘s pop-culture-centric view of its characters in Lady Bird. A rare moment of obvious unity between mother and child comes early, with them united in crying at the end of The Grapes of Wrath, and that is immediately derailed when Lady Bird lunges to follow that up with some music, explaining Lady Bird’s desire for something more versus her mother’s willingness to stay put before either of them says anything about it. Befitting the film’s almost exclusive following of Lady Bird’s POV, we get plenty of music from that point on. Amusingly, the use of music in Lady Bird almost comes off like a gentle ribbing of Women‘s immaculately-chosen soundtrack. One could uncharitably call Women‘s soundtrack a way for Mills to show what a cool record collection he has, but I don’t think anybody could register that complaint against Gerwig’s choices. Abbie would most definitely not abide by Lady Bird’s CD collection made up entirely of greatest-hits albums (Ronan’s heart-melting delivery of “But they’re the greatest, what’s wrong with that?” is almost enough to bring me to Lady Bird’s side, though), and instead of rhapsodizing about The Raincoats, Lady Bird is given to sharing factoids about “Hand in My Pocket” (she delivers that factoid with the same misguided pride as Jamie defending Talking Heads against accusations of them being “art fags”, and Tracy Letts doesn’t seem that much more enthused by it than the skate punk was). Her and her fellow theater kids throw themselves into belting out tunes from Stephen Sondheim’s Merrily We Roll Along, blissfully unaware of the fact that, as the script says, it’s “actually a pretty upsetting and adult show” about selling out and the death of youthful exuberance (Father Leviatch’s dejected “They didn’t understand it” after the first show’s performance is just as much about his cast as it is about his audience). And then there’s the much-remarked-upon use of the Dave Matthews Band’s “Crash Into Me”, an objectively creepy song about a stalker spying on a woman through her window that Lady Bird and her friend still find swooningly romantic, and Gerwig and the movie don’t mock them for this. In fact, when Kyle coldly says that he hates it at one point, the audience is totally on Lady Bird’s side as she meekly says she loves it. Both this and Women explore the meaning people find in pop-culture, but Lady Bird movingly doesn’t laugh when its characters use the alleged “wrong” pop-culture.

(SPOILERS for Lady Bird begin at this point)

As Lady Bird begins to end, Gerwig makes the connections to Women more overt. We see the two most direct echoes of Women in two identical shots of Marion alone at the kitchen table, continually writing something on a notepad and crumpling up the results. These shots are technically important to set up the later reveal of what she was writing, but they’re almost as crucial as the most direct rhyme with Women. In a film otherwise mostly dominated by tableaux, Gerwig quietly but noticeably dollies out of the kitchen in both shots, mirroring a shot early in the film that does the same with Dorothea alone at the kitchen table (mercifully, Marion hasn’t taken up smoking). That’s not all; we see, in a brief shot of one of those crumpled-up pieces of paper, that Marion has been given Dorothea’s story, that of a mother in her early 40s blessed with the opportunity to have her first child. And the film’s mother-child reconciliation is a familiar one as well, with the two briefly reunited by both driving on the wide-open, sun-kissed California road (this time, they’re united by cuts; suddenly Marion blissfully driving becomes Lady Bird doing the same). The ultimate significance of this moment in the grand scheme of things is left ambiguous, with the viewer denied any looks into their lives after that point, but its emotional wallop in the moment, for both us and Lady Bird, is immediately obvious. It may not be juxtaposed with the world at large, but this is a moment as powerful as any of the fundamental things of life.

Okay, maybe I am crying this time.

(That concludes the SPOILERS)

The End

This piece is coming out just short of a year from 20th Century Women‘s release, and I’ve spent almost all of that year building up to writing all this, to finally conclusively pinning down what makes this movie so special for me (and if I still look totally irrational having written this down, as Dorothea sez, “This is no time to be rational, sweetie, can’t you just go with this?”). Again, I sincerely hope you got something out of this piece if you liked the movie or not, or that it even finally convinced you to watch it. Just don’t blame you if you ruin your Christmas dinner party by talking about menstruation, okay?