After a meeting with a movie industry insider regarding a possible sale of his fiction to Paramount Pictures, H. P. Lovecraft didn’t have high expectations. “In cold fact,” the reclusive author wrote in a 1931 letter, “nothing of mine could ever be suitable for his purposes. Cinemas want action—whereas my one specialty is atmosphere.” Despite his generally anti-modern stance, Lovecraft enjoyed the movies, at least certain kinds: he expressed admiration for Charlie Chaplin and Douglas Fairbanks, Sr., but he saved his highest praise for epics that brought history and mythology to life, like the German silent Siegfried.

Lovecraft’s contribution to the literature of horror was a combination of scientific detachment and deep pessimism: he conceived of humanity as utterly alone and unprepared in a hostile, uncaring universe. Incomprehensibly alien and infinitely powerful beings such as Cthulhu, worshipped as gods by secretive cults, await the time when “the stars are right” and they may return to conquer the earth. A major theme of his stories is the price of knowledge, symbolized most clearly by the Necronomicon, a compilation of Secrets Man Was Not Meant to Know, of which even a casual glimpse can make one’s blood run cold or drive one to madness. The gothic trappings of many of Lovecraft’s stories—crumbling tombs, secret books, and family curses—aren’t so different from those of Universal’s horror movies, but with his emphasis on indescribable sights and sanity-destroying truths, he might be the original “unfilmable” author.

Eventually, decades later, as Lovecraft went from an obscure contributor to Weird Tales and other pulp magazines to the most influential American horror writer since Poe, filmmakers did mine his work for adaptation, at least selectively. Storylines were frequently changed, saddled with romantic subplots or altered to accommodate shooting locations and special effects budgets. Even beyond adaptations of specific stories, however, key ideas from Lovecraft’s stories became building blocks for new ones: films as diverse as Alien, Ghostbusters, and the Evil Dead series borrow names, themes, or imagery from the author’s extensive mythos.

As indicated by the letter quoted above, however, Lovecraft on the page is a different experience from most of the film adaptations of his work. To say that atmosphere is important to his work is an understatement: sometimes it’s the entire substance of a story in which very little (from the perspective of plot) actually happens. Even his more plot-driven tales depend on the author’s hypnotic, incantatory use of language (Lovecraft’s penchant for ten-dollar words—why describe something as “red” and “scaly” when you can call it “rugose” and “squamous”?—is a frequent target of derision from critics and affectionate ribbing from fans, but no one can deny that his is a unique voice).

By contrast, Lovecraft on film is often synonymous with over-the-top gore and slimy rubber monsters. Don’t get me wrong: Stuart Gordon’s Re-Animator is a blast, but it takes Lovecraft as a jumping-off point for Gordon’s particular brand of cosmic Grand Guignol. Lovecraft’s “Herbert West: Re-Animator,” upon which Gordon’s film is based, is uncharacteristically short on philosophizing and is more like the lurid, action-filled pulps that the author disdained, essentially a grisly update of Frankenstein. It’s also notable that Jeffrey Combs as West has much more personality than any of the reserved antiquarians that are Lovecraft’s typical protagonists. Ironically, most film adaptations distort Lovecraft by doing something that comes very naturally to cinema: putting humanity in the center of the frame.

There has been an explosion of independent Lovecraftian filmmaking in recent years, with fans adapting the author’s work in inventive ways (at lengths ranging from shorts to features) and sharing the results online and at film festivals. Two films that adopt period trappings, both from the H. P. Lovecraft Historical Society, are worth examining: a silent 2005 adaptation of “The Call of Cthulhu” and a 2011 version of “The Whisperer in Darkness.” One might expect a group calling itself the H. P. Lovecraft Historical Society to stick faithfully to the original stories, and in large part they do, but the two films reveal interesting approaches to the problem of adapting works heavy on ideas but light on dramatic action or characterization.

Published in 1928, “The Call of Cthulhu” is the foundational text of Lovecraft’s mythos: in it, an unnamed narrator inherits a collection of papers from his granduncle, a professor. Driven by curiosity, the narrator reads them and learns of a world-spanning cult that worships an ancient force or being known as “Cthulhu,” the facts pieced together by his uncle over many years and the discovery of which (it is implied) led to his death. Within this frame story, there are three episodes: a young artist dreams of a temple and the terrifying thing within it; in a flashback to 1908, police raid a frenzied, orgiastic ritual deep in the bayou of Louisiana; and a ship’s crew has a deadly encounter on an island in the South Seas, an island found on no map and which apparently rose from the bottom of the ocean at the same time as the artist’s disturbing nightmares. In retracing his uncle’s research and thought process, the narrator comes to the conclusion that Cthulhu is real, and that this knowledge will now make him a target for the sinister Cthulhu conspiracy. The end.

A silent version of “The Call of Cthulhu” is inspired: not only does it suggest the kind of film that might have been made out of the story at the time, it elides over the story’s lack of dialogue and puts the same distance between filmmaker and viewer that Lovecraft’s numerous second- and third-hand narratives put between author and reader in the original. (Even its relative brevity, less than 45 minutes, is era-appropriate.) In addition, it skirts the issue of giving actors lines such as “Ph’nglui mglw’nafh Cthulhu R’lyeh wgah’nagl fhtagn” without making them sound ridiculous. As far as atmosphere, the film has plenty to spare, whether depicting a clubby academic gathering, a benighted swamp, or a fogbound ghost ship.

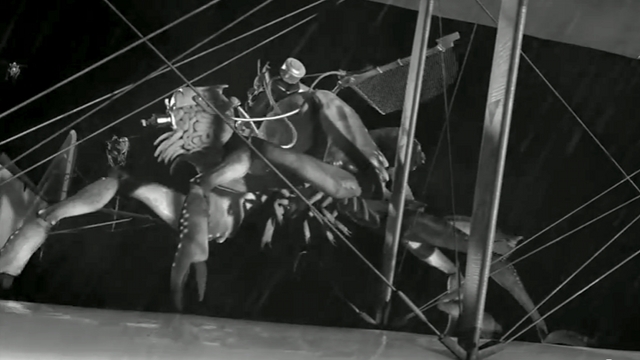

The film is quite straightforward in its adaptation (written by Sean Branney and directed by Andrew Leman), streamlining the narrative and adding visual details that flesh out the story—unsurprisingly for a group that produces props and documents for use in role-playing games, the production design is superb—but without major changes in the plot or characters. There are visual nods to Lang, Browning, and Cooper, and the actors’ performances are stylistically appropriate for the period. (In an extensive “making of” featurette, Noah Wagner, who plays the ship’s captain, jokes about the impeccable New Zealand accent he cultivated for the role. “It comes out in your eyes,” replies another cast member.)

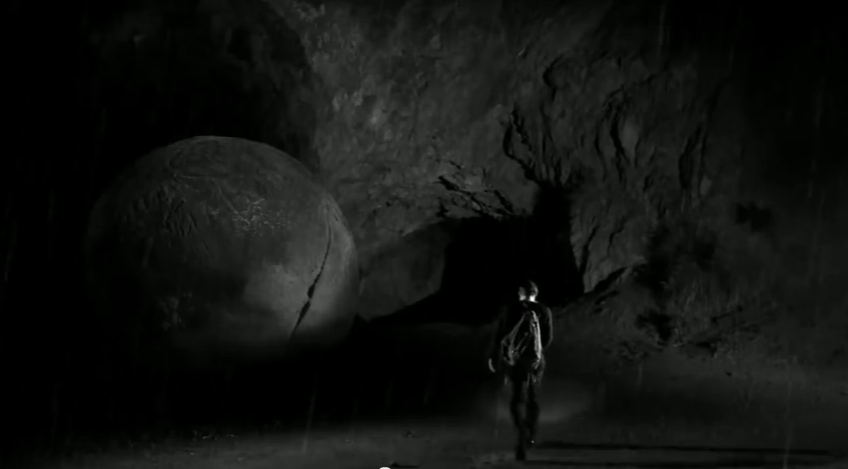

Given the small budget, the filmmakers make the most of the action sequences in the story, particularly a chase through the risen city of R’lyeh, but the emphasis is on the slowly dawning realization that dark hints from many different corners of the world are pointing to the awakening of something alien and inimical to man. The look of a silent film is achieved through a mixture of old-fashioned camera tricks—miniatures, forced perspective, and stop-motion—and modern digital effects, a combination HPLHS refers to as “Mythoscope.” The risen city of R’lyeh, with its “titanic blocks of stone” and angles that are “all wrong,” is particularly well-rendered, with the actors superimposed onto miniature sets, giving the whole scene a sense of unreality, like a nightmare fusion of King Kong and Land of the Lost. The Call of Cthulhu could accurately be called a fan’s film, but it’s more than that: it suggests an attempt to make a film that Lovecraft himself might have approved of.

The Whisperer in Darkness (this time written by Branney and Leman, directed by Branney) is in some ways a very different project, adapting and expanding Lovecraft’s 1931 story of alien visitors in the remote hills of Vermont as a full-length thriller. The original story is longer and more overtly science fictional than “The Call of Cthulhu,” but even with more detail and deeper characterization it still contains pages of dialogue-free narrative, and much of the dialogue consists of lists of unpronounceable names and references to other authors’ stories (part of the shared-world conceit that has come to be called the “Cthulhu mythos”).

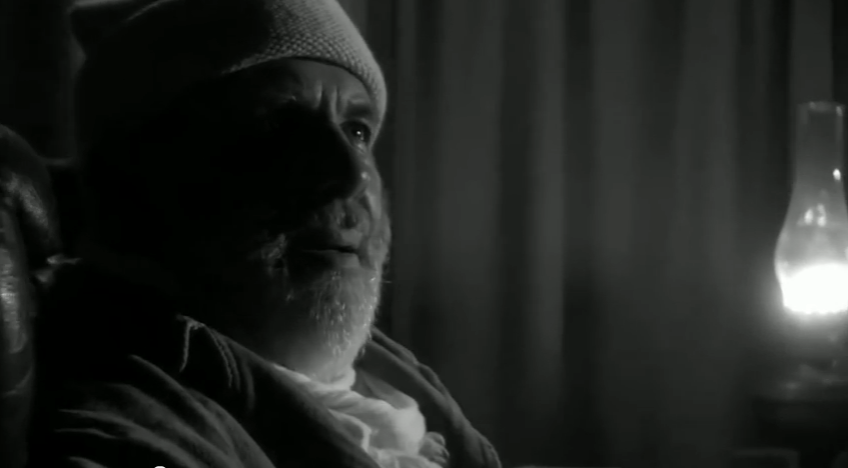

Following a series of heavy floods and rumors of strange bodies found in the rivers, folklorist Albert Wilmarth (Matt Foyer) is lured to Vermont by the prospect of confirming longstanding legends of inhuman visitors in the woods. Henry Akeley (Barry Lynch), a retired gentleman living alone in the Vermont woods, claims not only to have seen and heard the rumored creatures, but to have spoken to them; when Wilmarth arrives to visit, Akeley insists that the visitors are from another world and are eager to share their secrets, but it’s clear that something is very wrong.

Branney and Leman adopt a style reminiscent of Alfred Hitchcock and Orson Welles in their version, wisely omitting or splitting up the long speeches of the original, replacing words with action, and adding characters to turn monologue into dialogue. Welles’ adaptations, particularly his radio broadcast of The War of the Worlds, are a clear inspiration. In addition, a first-act radio debate between Wilmarth and iconoclastic author Charles Fort (Leman), added by the filmmakers, both delivers much-needed exposition and satirizes the kind of media-driven scientific “debate” that is still with us today.

I know this story well, as it’s one of my favorites, so while watching the movie I knew where it was going and what the big shock (Lovecraft’s story-ending punchline) would be: the film delivers that twist, but then goes a step beyond, developing an action-packed final act that follows logically from what has come before. It’s a clever balancing act, satisfying to fans of the original but leaving some surprises of its own; it’s also something that could only come out of Lovecraft’s Cthulhu mythos, with its established conflict between cultists and investigators, and the finale is reminiscent of a scenario from the Call of Cthulhu role-playing game (it came as no surprise to see Sandy Petersen, creator of the game, credited as an executive producer).

I was enthusiastic about The Whisperer in Darkness after being a fan of The Call of Cthulhu for years, but I wasn’t prepared for how gripping it is, and how the liberties it takes with the original story preserve Lovecraft’s themes without bogging down in minutia, as a strictly literal adaptation might. The HPLHS adaptation of “The Call of Cthulhu” trims much for its adaptation, but it isn’t nearly as elaborate in its reinvention of its source material as Whisperer. Both films are of interest not only to fans of Lovecraft, but to viewers and readers interested in the process of adaptation from literary sources; whether observing the letter or only the spirit of the original, Branney and Leman demonstrate what is possible when filmmakers put faith in the power of their source material.

The Call of Cthulhu and The Whisperer in Darkness are available on DVD and blu-ray from the H. P. Lovecraft Historical Society’s website; The Whisperer in Darkness is available for streaming on Vudu and Amazon Instant Video.