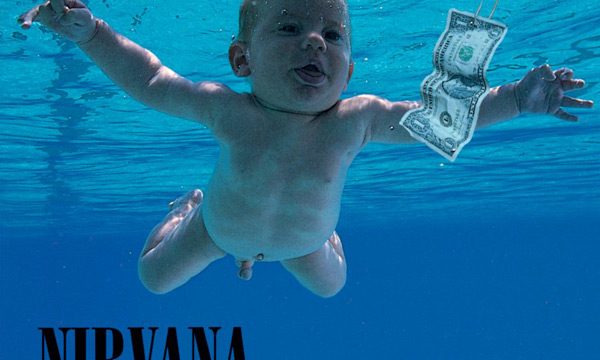

A standard line of dismissal for Nirvana’s behemoth-selling, culture-shaping sophomore record, Nevermind, is that it’s a fundamentally derivative work, more indebted to the more innovative bands that lurked in the ’80s underground (primarily The Pixies) than the product of any singular vision itself. I’m sympathetic to that line; I’ve even used it myself. It can be a little wearisome when taste-makers proclaim any work of art as a watershed moment that blew up its contemporary status quo (as is often said of Nevermind), and there’s clear evidence that the band is not some creatio ex nihilo but rather just another work in an established tradition. Another dismissive line (usually accompanying the first) aimed at Nevermind is that the record’s most distinguishing trait to set it apart from its alt-rock ancestry is its pristine production. The idea is that Nirvana cheated somewhat when achieving its fame: of course Doolittle could have had mainstream success if it had had a $65,000 production budget, the reasoning goes.

What the first criticism misses, I think, is that the act of synthesis is itself an act of creation. Undoubtedly Nevermind, with its loud-soft dynamics, slightly less forwardly mixed vocals, and aggressive-but-not-cocky songwriting, is the progeny of the ’80s underground and even ’70s punk (a lesser-cited but arguably just as important influence [if you look at it right, Nevermind is a pretty blatant Sex Pistols allusion). But it’s also true that Nevermind stands, alongside Pulp Fiction and, I dunno, maybe Lord of the Rings, as one of the foremost examples of synthesis as an art form. With this album, Nirvana distilled a lot of what made underground rock music so compelling and presented it in a condensed, energetic package. The criticism that it’s derivative ignores just how much skill it takes to make this kind of derivation so good, and it certainly downplays the extent to which, even within the world of the underground, just how skilled and singular Kurt Cobain was as a songwriter, not just on the rubric of synthesis but in sheer lyrics/melody weight. In other words: no, it’s not breaking new ground, but it’s treading that familiar ground with the fleetest of feet.

Which brings me to the easy rebuttal of the second criticism: who cares how slick the album is when it’s this banging? Nevermind is wall-to-wall excellence, from the iconic opening chords of the generation-defining “Smells Like Teen Spirit” to the closing dirge of “Something in the Way” (and hell, even to the nearly white-noise screech of the later-added hidden track, “Endless, Nameless,” the most Bleach moment here). By 1991, a couple years past the scrappy debut, the band’s ability to mix poppy melodicism with harsh noise had matured into one of the all-time great songcraft output. Realizing that “Smells Like Teen Spirit” isn’t even in the top-five songs on the record is just the tip of the iceberg as far as acknowledging the album’s deep, deep bench goes. It’s not just that there isn’t a bum track on here, something that’s true of many merely good albums; it’s that every song is a contender for a spot not only among Nirvana’s best but also among the best of the ’90s in general.

Nevermind frequently places on critics’ “best albums of all time” lists, a placement that usually means one of two things: it’s an important record for charting the history of the medium or it’s just full of great songs. And as important as Nevermind is for music history–derivative or not, it certainly helped to bring to the commercial mainstream a ton of bizarre quirks of the rock underground–I’d point to the songs as the major reason it’s had such staying power on those lists.

Of course, lists are poor substitutes for the actual experience of listening to an album. So go listen to this one. You’ve probably heard it before.