In chapter ten, “The Upas Tree: Making and Makers of Comic Books,” Dr. Fredric Wertham says he doesn’t want to get into personalities. That’s fine; that’s his choice. But by failing to do so, he’s left himself open for some serious criticism, more, I think, than he could have possibly known. So let’s do this, kids!

I think the thing that pissed me off most was the picture of luxury he paints Jerry Siegal as living in. He describes a picture that portrays the Superman creator as “lying on an oversized, luxuriously accoutered bed with silken covers, in a room adorned with draperies.” Leaving aside just how weird that image of Jerry Siegal is, he would two paragraphs later say that Superman had left Siegal behind.

For once, that’s absolutely true. There are three separate lawsuits between Siegal or his heirs and DC. It wasn’t until 1976, the year I was born, that Superman comics, movies, TV shows, etc., were required to mention that the character was created by Schuster and Siegal. Even in 1954, the men had no control of their creation.

But by not really looking into the two men, Wertham missed out on what Superman really represents. Mind you, Superman isn’t my favourite comic book character; I’m not sure he’s in my top five or maybe even top ten. I usually find him pretty boring. On the other hand, he’s also the one that I find most deeply moving on a mythological level.

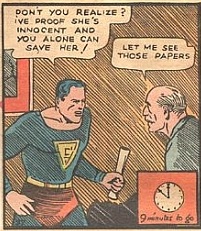

Wertham can say what he wants about Superman. He can call him a Nazi as often as he wants. But Superman was more than just the creation of two immigrants’ sons (technically, Shuster himself was an immigrant, but from Toronto, which kind of doesn’t count). His is the ultimate immigrant story and everyone knows it except Wertham. He isn’t the perfect Aryan; he is the “strange creature from another world.” On the other hand, he was raised American, in the American heartland. The choice of Kansas had to be deliberate. In Action Comics 1, he fought corrupt politicians and the mob and got an innocent person pardoned instead of electrocuted.

Does he solve problems with violence? Well, yeah. It’s not exactly unique to comics (an argument Wertham once again dismisses without really discussing). But he has also consistently tried to work in the system—he fights his way to give evidence to the governor instead of just rescuing the woman from prison, for example. Superman is supposed to represent Truth, Justice, and the American Way, and it turns out that, yes, the American Way does indeed involve some punching.

Moving away from Superman, Wertham elsewhere in the chapter says that there is no artistic writing in comics. But by 1954, twenty-seven stories by Ray Bradbury had been adapted for EC Comics. This includes after the publication of Fahrenheit 451, when presumably the money from EC wasn’t coming to much. In fact, while Wertham claims that basically everyone in the industry hates it and wants to be doing something else, Ray Bradbury happened to note that two of his stories had been combined into an EC comic and wrote a note praising it but observing that, somehow, they’d forgotten to pay him? And it went from there.

He also just does not seem aware of how desperate people were and are to work in the comic book industry. Yeah, there are people who aren’t so much, but I think Wertham would have been genuinely shocked to learn how many people considered working for DC or EC to be their fondest hope. There are people working for DC and Marvel today who started submitting work in grade school.

I mean, there’s a lot of other stuff in this chapter. There’s a throwaway reference to Puerto Rican’s getting their “first taste of American culture” from comic books after moving to New York, which made me want to sing Sondheim at him. (“Puerto Rico’s in America!”) He ignores the fact that maybe, just maybe, there aren’t a ton of people whose life goal was to work for Time or Newsweek or what have you for the rest of their lives and that “I don’t want to work here forever” isn’t as big of a condemnation of the industry as he thinks.

There’s a lot of misunderstanding about the nature of the publishing industry; he says that the printers of “legitimate” magazines don’t emphasize their connection to comics, but then, how often does Time remind you that it’s from the same publisher as Sports Illustrated and vice versa? He criticizes the fact that there are many, many places where you couldn’t buy a book but could buy a comic without looking into why there were that many places where you couldn’t buy a book. And we’re apparently talking whole neighbourhoods, here.

Then, there’s this weird paragraph.

I have sometimes indulged in the fantasy that I am at the gate of Heaven. St. Peter questions me about what good I have one on earth. I reply proudly that I have rad and analyzed thousands of comic books—a horrible task and really a labor of love. “That counts for nothing,” says St. Peter. “Millions of children read these comic books.” “Well,” I reply, “I have also read all the articles and speeches and press releases by the experts for the defense.” “Okay,” says St. Peter. “Come in! You deserve it!”

I don’t even know what this means. I don’t even know where to start figuring out what this means. Like, reading those articles is a good thing? Or Wertham believes you get into Heaven for just doing unnecessary and difficult stuff? Or what even is this?

He claims that every art has critics and that comics don’t, but were there really critics of the “legitimate” magazines that I don’t know about? Who criticizes Vogue professionally? He claims that the publishers of children’s books don’t hire experts to defend them, but that’s flatly wrong and I know it, having read a book about the history of children’s books. Really, it’s more of the same that doesn’t even have anything to do with the chapter title.

I could deal more with his own words and less with Superman, but we’re having the hottest days of the summer so far right now, and it makes me grumpy. I’d much rather think about Superman as a sociological phenomenon than Wertham as a cultural critic. It’s more interesting and less aggravating.