In the interest of full disclosure, I’ve got to admit that I had not heard Unknown Pleasures, Joy Division’s iconic and influential 1979 debut, until just a couple days ago. I guess you could say that the pleasures of Unknown Pleasures were… unknown. [crickets]

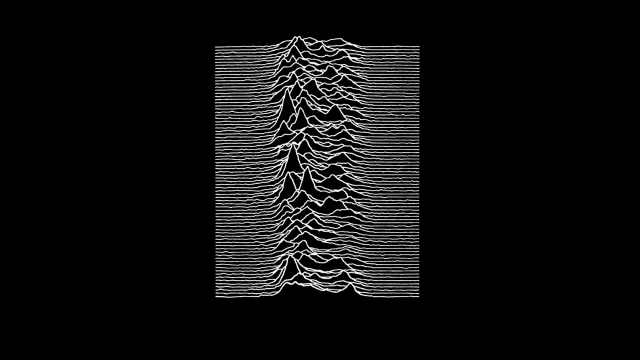

Okay, in all seriousness, it’s really difficult to review such a historically huge album cold, not to mention nearly 40 years beyond its original release. I lack the context; I lack the accumulated affection that only comes from hundreds of listens over multitudes of months (and years). I’m familiar with the culture surrounding the album, the memes, the t-shirts, the Mickey Mouse t-shirts; the album’s legacy, both as a post-punk touchstone and as a sonic influence on all sorts of bands in the ’80s and ’90s.

All of this swirls around in my head to the point that, try as I may to approach this thing blank slate, it’s impossible to not be disappointed that in the end, it’s just an album.

Granted, it’s a very good album. Whether or not I’m prepared to regard it as great (much less as great as its legacy commands) is something I’m going to have to put on hold until I’ve had a chance to spend more time with it; see incubation period for album affection above. The record’s dark, cavernous ruminations on emotional trauma strike me as something I would have loved on sight in my late teens, but a decade later, I’m a bit less easily seduced by those sorts of theatrics. This, if I can make a generalization, strikes me as a basic principle for the record: immediate for late teens, slightly more distanced for those finding it later in life. Although maybe I’m wrong.

If you can’t tell already, I’m not blown away. It’s hard to unhear all the ’80s Goth-tinged post-punk bands drawing on this sound, bands that I have significantly more affection for by virtue of my having listened to them since… well, my late teens. Echo and the Bunnymen comes to mind particularly: Unknown Pleasures shares that noisy, theatrical flair with everyone’s favorite coney-related band, although it’s considerably noisier and spookier than most of Echo’s output. That spookiness isn’t to be dismissed; in fact, it’s central to the impact of the songs here. The way the production places Ian Curtis’s vocals at the back of the mix, a technique I usually find frustratingly airy, has the effect of making the music feel dank and oppressive and sinister in a way that few bands manage, and credit goes almost entirely to just how heavy the instrumentals feel, as if they were drowning Curtis’s voice in sludgy, brackish cave water. An unsettling trick, to be sure.

This is good music, sad music, late-night music, and I like it. Don’t hear me say that I don’t. But I don’t have the time or context yet to truly love it, and that’s where y’all come in. Surely one of you readers loves this record dearly, and I’m excited to hear your enthusiasm for it. Comment away.