We all probably would have been better off if Dr. Fredric Wertham had stuck to working with underprivileged black teenagers. Certainly his place in history would have been quite different. His analysis into the damages segregation caused were used as part of the evidence that led to the US Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education; he showed that segregation did, indeed, have a detrimental psychological effect on those populations. You just kind of hope his methods were better for that than they were for his writing on popular culture.

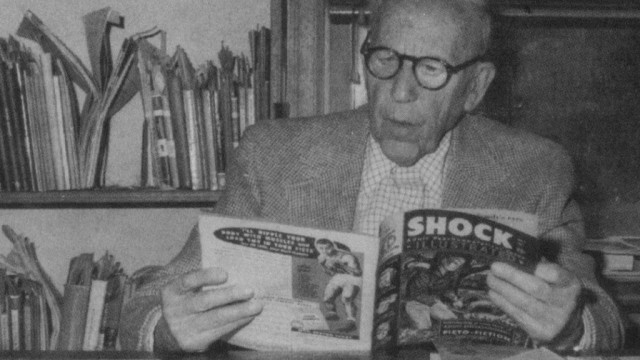

In 1954, Wertham published the infamous Seduction of the Innocent. My copy arrived in today’s mail. The book was originally published by Rinehart & Company. My copy, however, is British, because I was able to find a British edition for $20; American editions are insanely expensive, especially first editions, and the book is now out of print. All references will be to the edition I now own, published in 1955 by Museum Press Limited. The book is 397 pages, not including a sixteen-page insert of panels and covers from assorted comics. There is no index.

I’ve long held that every generation has its own moral panic about the media corrupting the next generation’s youth. In the ’50s, it was comic books. Believe it or not, there was an entire Congressional investigation into the subject, chaired by New Jersey Senator Robert Hendrickson but quickly taken over by Tennessee Senator Estes Kefauver, another person who would have been better served by history if he’d stuck to civil rights. (Kefauver, along with Al Gore, Senior, and Lyndon B. Johnson, refused to sign the so-called “Southern Manifesto,” officially the Declaration of Constitutional Privileges, an segregationist document.) There was real concern that unfettered access to comic books was destroying America’s youth.

I know—it’s weird. Comic books. The biggest movie in the country right now is based on a comic book hero older than the hearings, one who debuted right in time to start punching Hitler. And it is true that not all the comic books at the time were Captain America, but still. It seems so silly. These panics often do, after the fact; another item in my collection is the DVD of the 1982 made-for-TV feature Mazes and Monsters, wherein a young Tom Hanks is driven to madness by the forces of not-at-all Dungeons & Dragons. Go back a generation before Wertham, and you hit panics over the easy availability of paperback books, surely the most ludicrous panic to date. I’ve got examples going back centuries.

Even beyond “the kids like it and we fear it” (Wertham also had bad things to say about movies and TV), we probably shouldn’t downplay the Communism thing. While, in the end, it would turn out to be just a Red Herring, it is probably no coincidence that the height of comics hysteria happened in the first years after the Soviet Union exploded its first atomic bomb. Yes, these panics happen all the time, but it seems to me that they are more frequently acted upon when there’s some external fear to be ignored in favour of focusing on something relatively unimportant.

I mean, don’t get me wrong—some of the horror comics were graphic. And as we’ll see, not everything Wertham said was totally lunatic; he did manage to pick up on the idea that there’s something going on with all the tying up of Wonder Woman. However, the thing he was most accomplished at was extrapolating beyond his facts. So not only was Wonder Woman into bondage, she would therefore turn little girls who read the comics into lesbians. What’s more, he believed, as Joe Breen did about the movies, that all comics should be completely acceptable for those little girls, that there was no such thing as an adult comic.

What, then, shaped Fredric Wertham himself? He was born Friedrich Wertheimer in Munich on 20 March, 1895. He studied at several prestigious European universities, earning his MD from the University of Wurzburg in 1921. He studied under Dr. Emil Kraepelin, and he corresponded with and visited Sigmund Freud—an interesting mix of influences, given their opposing views on what causes psychological problems. As we shall see, Wertham clearly leaned more strongly toward the Freudian instead of Kraepelin’s view that mental health problems were likely biological problems, and probably genetic.

In 1922, Wertham immigrated to the US and started work at Johns Hopkins. In 1932, he moved to New York and Bellevue, where he worked mostly with criminals. In 1946, he opened the Lafargue Clinic, a low-cost psychiatric clinic in Harlem, where he saw mostly black teenagers. In short, of the thirty-two years spent in the US before publishing Seduction, twenty-two were spent working with the underprivileged and with actual criminals. By all accounts, he did good work in those years.

However, he seems to have wanted to find the root of his Lafargue patients’ problems. Obviously, he thought, poverty and societal ills and so forth were part of it. However, he came to believe that things the average person thought of as light entertainment were instead destroying his patients’ lives. His campaign was begun, and it culminated in the book we will be discussing in this space over the weeks to come. After we’ve finished, I’ll add a follow-up giving a brief overview of what actually happened in the comics industry as a result of Wertham’s—and Kefauver’s, and so forth—work.

Next week, we’ll begin with Chapter One: “Such Trivia As Comic Books,” which Wertham subtitled “Introducing the Subject.”

Note: My copy, as I said, is British. It includes an introduction I can only assume is not in American editions, written by Randolph S. Churchill. This is the son of Winston, also an MP but a fairly dissolute one, from what I can tell. He had nowhere near the illustrious career of his father. Indeed, Wikipedia informs me that, the year this copy was published, his career was considered “already hopeless.” (Cut me some slack—while I have reference books about comics, I don’t have any about Randolph Spencer-Churchill and indeed had to look him up to be sure who he was.) However, he does appear to have latched onto this philosophy enough to contribute the introduction.

The introduction is some two pages (not included in the page count), though it would probably be closer to four in the print used for the rest of the text. While on the one hand, it gives a little valuable information for British audiences about obscenity laws in the UK, it manages to be both rambling and imprecise. It complains about the British courts’ obsession with the Sixth Commandment without explaining what the hell he means by that or indeed whose numbering system we’re using. (I was raised Catholic, where that’s “thou shalt not commit adultery,” but I’m not sure how the Protestant “thou shalt not kill” is more relevant.) He also gives a strong argument that “obscene” should not refer exclusively to sex, or anyway what he thinks is a strong argument.

Perhaps the most telling paragraph is this one, which reads as nothing so much as a desperate struggle toward relevance.

Surely the right course in this situation is for the Director of Public Prosecutions to initiate an action against some firm who are seeking to enrich themselves at the expense of the minds of young children? If the magistrate or judge should prove to be so illiterate as to fail to punish the defendant, then will the time to consider an alteration in the law which would sweep away the unrealistic judgement of Lord Justice Cockburn [cited two paragraphs before as having established that obscenity “is whether the exhibition or matter complained of tends to deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to immoral influences”], thereby giving greater protection to publishers and laying the purveyors of pornographers and crime open to the fullest penalties of the land.

In fact, British obscenity laws would be overhauled only a few years after this book went to press, but one suspects not in the direction Churchill had hoped.