Like the two-party system, the notes and scales used in almost all the music we hear are a local, historical accident that’s been around long enough to appear as unalterable and even necessary. One of the blessings of art is that it allows not just for expression, but for the construction of alternate worlds and ways of being; there’s a unique shock from a work that reveals an entire language to us. A very few composers have chosen to work outside, or more descriptively between, the twelve-note system that’s been in place since Bach. One of them is the classically trained Easley Blackwood, and his Twelve Microtonal Etudes is one of the lost masterpieces of the 20th century, strange and playful and perfect. (Cedille Records remastered and re-released these, along with a Fanfare for the great Chicago radio station WFMT and a guitar suite. The release also includes Blackwood’s extensive descriptions of what he’s doing and why.)

[Readers not puzzled by the terms “equal temperament” or “just intonation” can skip this paragraph.] The system of notes derived from ancient Greece is called “just intonation.” In this system, the intervals–the distance between the notes (technically, the ratio of frequencies)–are considered acoustically pure. Take the note C: the C one octave above is twice the frequency (2/1); the perfect fifth (the G above) is 3/2 the frequency; the major third (E above C) is 5/4 the frequency; the minor third (G above E) is 6/5 the frequency. This sounds great, but there’s a catch: because these intervals are all of different sizes, going from one key to another requires new notes. A C in the key of C has a different frequency than a C in the key of F-sharp. In the Baroque era, when modulating between different keys became a fundamental part of the musical language, this meant building instruments with, as the Austrian King said, too many notes. (Look up some keyboards from the period and be amazed.) Various “temperaments” were tried: altering the notes and the intervals just a bit to allow modulation between keys. (The interval that stays the same is the octave, always twice the original frequency.) After a lot of experimentation, the solution that resulted and has remained for the last 300 years or so is “equal temperament”: there are 12 notes to the octave, and the acoustic distance between any two adjacent notes–a “semitone”–is the same. (Each note has a frequency approximately 1.059463 times the adjacent lower one. That’s the 12th root of 2, so going up 12 of them gives you twice the original frequency, or one octave up.) Equal temperament results in two things: no interval sounds as pure as in just intonation, but these twelve notes work in any key without the problem of having to build new instruments in the middle of a performance.

In the last century, most exploration of alternate tunings has been in the realm of just intonation, with Harry Partch’s scales, instruments, and performances as the most famous. Blackwood chose instead to explore equal temperaments, discarding the traditional twelve for 13- to 24-note scales, one etude each. This choice allowed him to compose with many of the techniques of classical music, particularly the ability to easily modulate between keys. For each scale, Blackwood sought the most traditional way to compose in it, looking for harmonies similar to the classical triad (C-E-G would be the best known), diatonic scales, chromatic ornamentation: for example, he describes the 16-note scale as “four intertwined diminished seventh chords,” just as the 12-note scale is three intertwined diminished sevenths, and he uses that as the basis for composing in it. Blackwood’s Etudes fit nicely in the tradition of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier and Paul Hindemith’s Ludus Tonalis: works that are meant to be not just artistic, but pedagogical, even fundamental, a demonstration of what works in a given system. Blackwood sez “I would love to hear someone else’s interpretation of these scores”; given how many different interpretations and orchestrations of the Well-Tempered Clavier are out there, that would be a great musical thing.

What’s striking on the first hearing (and even many hearings after) is how unusual these pieces aren’t. That’s down, first, to Blackwood’s superior technical skill as a composer. What animates the etudes is the joy of making (and hearing) good music, not a proof-of-concept of a theory. The avant-garde in all arts is full of people who have cool theories but no skill in realizing them, and that results in art that gets the label “challenging” as an excuse for being no damn good. (When this art becomes part of an institution, it’s saying quite literally to the viewer or listener “fuck you, pay me.”) None of these pieces are like that; among Blackwood’s other talents, he’s so good with subtly ornamenting his melodies. No piece wears out its welcome, as Blackwood constructs each with as much sense of forward drive as the scales will allow.

That leads to another reason these pieces come across as not-unusual: Blackwood fully works out the implications of each scale. Languages, someone said, differ not so much in what they can express but what they can express easily, and Blackwood finds for each scale what it does best. For example, the 23-note scale doesn’t have much in the way of good-sounding triads, so it’s not going to have that sense of forward motion of a traditional tonal piece. (I’ve heard other composers who use this kind of scale to simplyjamabunchofnotesreallyclosetogether which is acoustically interesting, but not musically so.) He found, though, nearly exact versions of two Indonesian modes (pelog and slendro), and constructed a beautiful static piece around them, with melodies tracing larger and smaller circles around each other:

This needs to be played by a steel drum band. It could be something by Brian Eno or Harold Budd, a piece of world music not quite of this world; you’ve heard something like this before but you won’t hear anything like it again.

In contrast, in the 21-note scale, “major and minor triads and keys are relatively consonant,” which makes sense–21 is divisible by 3, so the major thirds (C, E, G#) will be identical to the 12-note scale. Blackwood uses that and cuts loose with a four-part suite that could easily have been written by Vivaldi, with the same brightness and energy and feel for a memorable melody.

(He recognizes that the scales are slightly out of tune, which actually creates a somehow elegant kind of strangeness in those melodies.) He handles counterpoint a lot better, though; all four movements are canons at different intervals, which gives the feeling of constant, shifting motion in all the registers, not just a single melody with bass support. Placing it all on the old-school synthesizer makes it call up and exceed Wendy Carlos’ Switched-On Bach.

Blackwood could go all in on that strangeness when he had to, though; the 13-note (“the most alien tuning of all”) scale produces something so disturbing and brilliant that I want to demand he write some horror scores in it. (It would be perfect for The Descent, or maybe a remake of Gaslight.) It’s a music that’s without the triadic basis of all the harmony we know. We can recognize that this isn’t just out of tune, but in tune in some other way. The etude recalls the sick music near the end of Safe, that creation of the Uncanny that horror does so well: that moment when our brains try to process an object as something recognizable, and fail. For a moment, we hear something that has its own coherence, a truly alien thing:

As ever, Blackwood’s infallible sense of counterpoint works to keep the music just dense enough to be interesting but not overwhelming, and to not hide the strangeness of it all.

Although it’s not formally part of the Etudes, the Fanfare (in 19-note tuning) allows Blackwood to kick out the jams and have a variety of notes and triads just not available in the 12-note scale. This piece has so much energy and joy that it makes me wish for some 19-note equal-tempered keyboards out there, or maybe electric guitars in this tuning. (Glenn Branca has done a lot of work with just-intoned guitars, and he’d do wonders with these notes.)

In pieces like this and the Well-Tempered Clavier and Ludus Tonalis, the composer isn’t trying to express anything personal, or really anything about meaning at all. Blackwood sez he wanted “to express what is inherent in each tuning by the most attractive possible musical design.” Done right, you get the feeling of a piece not bound to a particular self, but that of a natural artifact from a different nature. Done right, you get music that’s eternal.

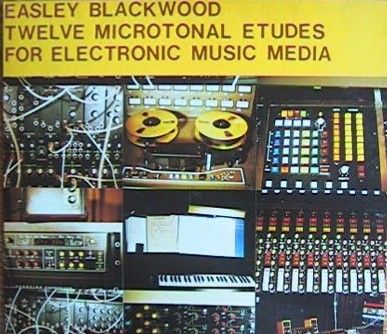

Blackwood made these pieces with the best technology of 1980, which means it sounds pretty dated to our ears. That’s part of the charm, though; all of these have a homemade feel to them, the musical equivalent of unvarnished and unpainted furniture. They call back to the Baroque era, where you would play your own pieces on a clavichord and no one outside the room would know; and they connect to the do-it-yourself practice of the contemporary punk movement. To my knowledge, “garage classical” isn’t a genre, but these pieces should be part of it anyway.

That sense of a handcrafted, even private work, and the combination of the alien and the accessible defines all the pieces here, and it somehow feels very American. At its best, or maybe at its most characteristic, the American avant-garde has a playfulness to it that the European version lacks. Think of Charles Ives throwing together as many marches and bands as he could, John Cage with his music for twelve radios, the jazz of John Coltrane, the surfaces of Morton Feldman, the zinging cartoon music of Carl Stalling: this is all music of incredible intelligence and complexity, but none of it subscribes to or defines an overarching aesthetic theory. Probably the composer most antithetical to the American tradition would be Karlheinz Stockhausen; the story still floats around among musicians that he chased Feldman around the Darmstadt music festival demanding to know “what’s your system?” (I’m not saying it’s true, it’s just something I heard.)

The myth of the frontier has been justly attacked in American culture, but it’s still there, and I suspect it has a lot of influence on those who work in artistic frontiers. The spirit of the myth isn’t one of theory, and it isn’t even one of justification: it’s experimental and fun, with a crucial sense of lowered stakes. The playfulness of it comes from that, the sense that you didn’t know if what you were doing would work, and it didn’t matter. (In Blood Meridian, one of the great novels of the frontier, the Judge reminds us that play is a nobler activity than work.) Try something, and if it doesn’t work, you’ll try something else; you might die but you won’t be embarrassed. The frontier was a place where you did things and no one had to know, very much like a laboratory, or a garage. And if your exploration worked, you came back not with something complete but a map of what was there, and you invited others to explore it. The avant-garde works of Elliott Carter and Milton Babbitt belong more to the European tradition: they are great monuments, theorized and explained and with lots of texts, like guidebooks, available for those who want to tour them. Blackwood’s etudes are the first sketches of a new world, and even if few have followed him into it, they still have their own beauty and identity.