High-Rise ends with “Industrial Estate,” a song by the post-punk iconoclasts The Fall. That just about sums up the film’s offhand brilliance. Directed by Ben Wheatley, it gets nearly every little detail right, which is vital when adapting the novel of the same title by J.G. Ballard, who uses every possible suspension of disbelief trick that literature can provide.

Wheatley sticks to Ballard’s minimalist plot, the three-month social collapse experienced by the tenants of an ultramodern apartment building. He also retains Ballard’s misogynistic blend of sex and violence, which permeates the air like the stench of rotting garbage strewn in the rooms and hallways.

His chief innovation is to set the film in the mid-70s, when the novel was published. This setting celebrates the looser attitudes about the decadent pleasures of drinking, drugs, and promiscuity, while sounding an alert about what’s soon to come: the rise of Margaret Thatcher and a winner-take-all ethos that would further intensify a British sense of class consciousness.

From a contemporary viewpoint where postmodern overload is the cinematic norm, High-Rise measures up to expectations. Scenes that will be seared into your memory include a slow-motion suicide of a man diving off an upper floor onto a car in the parking lot, a supermarket riot, a swimming-pool graveyard, and a trippy party sequence set to “Outside Your Door” by Can, the groundbreaking German art-rock band that influenced The Fall and have become a musical resource for edgy films set in the 70s, like Inherent Vice (2014).

Yet, for all the style High-Rise projects, it’s grounded in remarkably strong performances. The protagonist, Dr. Robert Laing, a teacher of medicine, is played by Tom Hiddleston. Laing has the refinement and training of a man, described by an upper-class toff, “who knows his place.” Indeed he does—as the montages that collapse time move in and out of his fractured vision of the reality being transformed by the building, he instinctively waits for the new order, over which he will preside.

The old order pits the upper-class architect and designer of the building, Anthony Royal, played by Jeremy Irons, against a middle-class documentary filmmaker, played by Luke Evans, whose animalistic presence—he’s named, of course, Richard Wilder—acts out Ballard’s typical commentary about how the media amplify anti-social impulses. That both Royal and Wilder die at the end of the film somewhat deescalates the animosity between those on top of the social hierarchy (the upper floors) and those on the bottom (the lower floors).

High-Rise therefore can be interpreted as an allegory of devolution that rationalizes the fixed roles for women in the new order. Playing characters that border on stereotypes, much credit ought to be given to Sienna Miller and Elisabeth Moss for making these women appear human in an especially dehumanizing environment. What’s strangely interesting about the film, in this respect, is that little distinction is made between the social value of caretaker and sexual partner.

High-Rise therefore can be interpreted as an allegory of devolution that rationalizes the fixed roles for women in the new order. Playing characters that border on stereotypes, much credit ought to be given to Sienna Miller and Elisabeth Moss for making these women appear human in an especially dehumanizing environment. What’s strangely interesting about the film, in this respect, is that little distinction is made between the social value of caretaker and sexual partner.

And this all culminates in the question asked by the film: who, really, are these people? Like in all of the best dystopian satires, they’re just one step removed from ourselves. For all of the fantasies of dancing on the abyss, this is not escapist fare. Even the orgy scenes that proliferate at the end of the film have a choreographed realism that insists these scenes are to be taken as a prominent feature of the social transformations we are watching.

This staging is reminiscent of the acts of sex and violence presented in A Clockwork Orange (1971); its promotional artwork is very similar to that of High-Rise. But another film, also directed by Stanley Kubrick, that comes to mind is Dr. Strangelove (1964), which depicts the failure of rational thinking to prevent a nuclear apocalypse. High-Rise is like that film, minus the bomb: a march backwards to primal times.

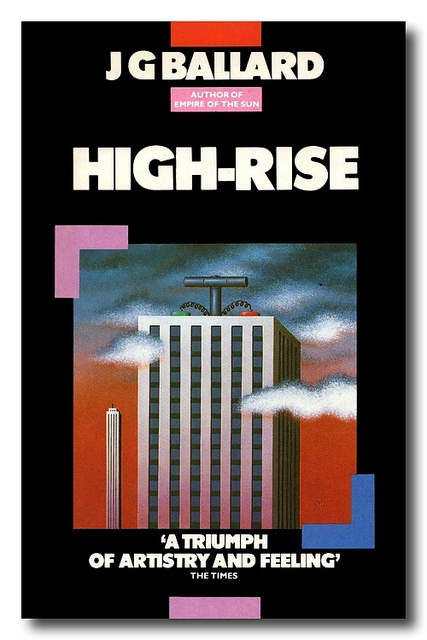

The explosion is thus more conventional. On the cover of the copy of the novel I read several years ago, the apartment building is shaped like a detonator. Both the novel and film depict the coiled social pressures that breed conflict, pressures which inform the songs of The Fall and the recent inheritors of the band’s junkyard riffs, such as Protomartyr, a group from the industrial landscape of Detroit.

The explosion is thus more conventional. On the cover of the copy of the novel I read several years ago, the apartment building is shaped like a detonator. Both the novel and film depict the coiled social pressures that breed conflict, pressures which inform the songs of The Fall and the recent inheritors of the band’s junkyard riffs, such as Protomartyr, a group from the industrial landscape of Detroit.

Sure the film has its share of excess. There are, for example, not one, but two cover versions of “SOS” by ABBA: the first, an instrumental, the second, a dirge-like rendition by Portishead, that elevate the grim irony of Laing, at the beginning of the film, getting thrown out of a party hosted by Royal in his penthouse suite and, at the close of the film, the end-of-the-world partying of those in the suite, while those on the lower floors appear more stoic.

If there’s any criticism, it’s that High-Rise locks early on into a formula that may too readily suggest The Hunger Games franchise (2012-2015) for an adult audience. While it’s understandable that there’s little space or time for critical reflection—the film stakes all of it on the final shot of a child dressed in the costume of the ruling class, there could be a more coherent representation of the building itself, which becomes a stronger character in the novel.

Yet in one noticeable way the film surpasses the novel. By being made now, but being set in the mid-70s, the film conveys in a memorably disturbing way that little has changed between then and now—if anything, it has gotten even worse. The film argues that the great lie we have been sold by neoliberal politicians such as Thatcher is that the more efficient—rather than the more empathetic–a society is, the better lives it can offer for all of its members.

In the few scenes of Laing working as a teacher, we’re reminded that public education is, at the moment, falling apart just like the apartment building in which he lives. The signs of what neoliberalism is doing to us are on full display: visit your local public university or high school, read the news about lead poisoning and the collapse of infrastructure and services in underfunded cities, or watch the inferno, fueled by climate change, consuming parts of Canada. The uncanny feeling the film projects is that if we’re just now hearing the warning, it’s already too late. This pessimism makes High-Rise unmistakably relevant.