“Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” must have looked like a natural on paper, but, alas, the completed film is slow and disappointing. This despite the fact that it contains several good laughs and three sound performances. The problems are two. First, the investment in superstar Paul Newman apparently inspired a bloated production that destroys the pacing. Second, William Goldman’s script is constantly too cute and never gets up the nerve, by God, to admit it’s a Western.”

Roger Ebert -1969

I’m very hard pressed right now to not just link to Ebert’s review*, both written and visual, on this iconic late 60’s western. He’s exactly right, for a film that is so famous, dripping with awards and preservation, I was left in the camp of “I don’t get it” once I left the theater last night. The end of Ebert’s review sights the film harping on the iconic ending of Bonnie and Clyde, which coincides perfectly with my class on New Hollywood Cinema as we had just watched the film two weeks before. Bonnie and Clyde marked the beginning of the New Hollywood trend, where directors emerged from the woodwork with characterized films that challenged and triumphed over the tedious nature of Hollywood prior. This is characterized by the film’s “ultraviolence” most notable in the final scene. But while Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid wants to hit those notes, it somehow comes across as baffling in its simplicity and extreme lack of plot or characterization which the former film was rich with.

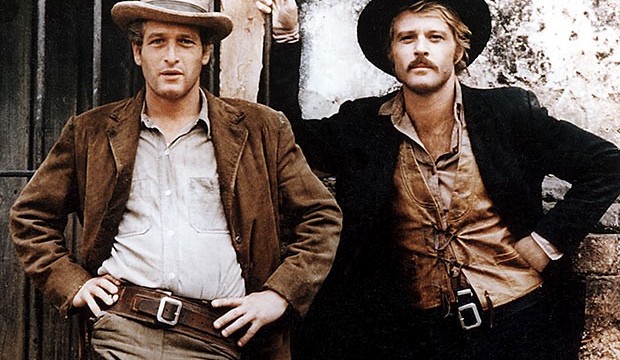

What’s the most fascinating thing though is the film’s opening, shot in a sepia tone as though we were looking through a record of old photographs come to life (which is used to ridiculous effect later on in the film), and creates this dreadful tension and sense of danger. The opening card game scene is out of a completely different movie, as though when Paul Newman and Robert Redford stepped out of the doors into the beautiful colored world no more threatening than a Disney film, they meant to exit through the backdoor where the Sam Peckinpah film was waiting to begin. The only thing that makes this film tolerable is the nature of Newman and Redford’s easy comradery and their charisma and flirtation with everyone around them. Somehow this film makes a lighthearted scene out of an implication of sexual assault, and even keeps it tasteful by not showing any breasts. But that’s the nature of the film, opting for a amusing if not ridiculous bike-riding scene cued up with “Raindrops Keep Falling on My Head”** instead of making an actual western.

That’s the major fault that Ebert saw as well, and pardon the rhyming, but the film is both very lame and tame at the same time. There are inceptions of plots, characters, where you assume that the film is directing the story towards. Early on Butch Cassidy and his gang rob a series of trains and earn the ire of a wealthy businessman from whom they’ve been stealing from, so he sends a posse of the biggest threats in the west to find Cassidy and the Kid, but…nothing happens from it. The film spends and agonizingly long period of the two running away from their captors but there is still not any tension, which isn’t helped by the cutesy dialogue that the two share as though this is a minor inconvenience as opposed to a legitimate threat. By the third or fourth time one of the pair asks the other, “Who are those guys?”, we the audience have gained nothing from this. At this point we know nothing about who is chasing them, and more so we still don’t know the inner workings of our leads. The film is so passive in its narration and development of the leads that it there is no tension or reason to even care.

Alternatively, there’s a suggested love triangle involving Katharine Ross’s character, she probably has the most complexity given to her even though she is so underused regardless. Again when the three go out to Bolivia, there’s an entire montage dedicated to their escape up the East Coast with implications of tension between the three as there is some kind of unrequited love between Ross and Newman. But the film never does anything with it, nor with Ross and Redford’s strenuous relationship (if I can even call it that). So when the film picks up some steam once they reach Bolivia, Ross’s character sets out as their translator and accomplice, shooting guns and assisting in bank robberies without any qualms, she’s a natural. However her development is immediately halted once she realizes that Butch and the Kid are doomed to be running from the authorities forever and decides to leave them there to die, a very wise decision on her part sure, but the disinterest in sending her character off properly leaves a lot to be desired since she is the most interesting character out of the three.

While the film is only 110 minutes, it’s hard to decide if it’s worth the wait to watch the film’s climatic shootout. A fun scene that has the most obvious and rightful conclusion, it once again is halted by the rest of the film’s lack of dramatic stakes and banality of Butch and the Kid. They’re robbers, that’s all they know how to do, the Kid can’t swim, and they’re funny. That’s it, that’s all we take away by the time the film reaches this conclusion where the two are bleeding out and planning to head to Australia next. There’s just so little to their characters and to the world they inhabit, that the final shootout is mostly entertaining because it’s the only time the film comes alive as far as an arc goes. The two blissfully go out guns a-blazing to their doom but they still manage to keep the light flirty conversation, rather they die like this than rot in jail.

Their punishment for defying authority and committing murder doesn’t feel as dark or controversial as Bonnie and Clyde’s demise at the end of that film. Bonnie and Clyde as a film is a spiraling rabbit hole of desperation and greediness that could only end is such a huge bloody affair; why do we the audience and certain characters in the film glorify Clyde and his gang? The moment when Bonnie’s mother strips down her daughter and lover for their ways, that’s the movie talking to the audience, asking them these questions as to why should we romanticize something like robbing and shooting people? There are no moral questions to be found in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, they are trapped in a stagnated world of little development, little interactions or reactions, and no reason for us to care for these glorified criminals.

Yet this film won Best Original Screenplay (which is fascinating considering this was up against Easy Rider and The Wild Bunch). This film won Best Original Score. I respectfully disagree on both counts. The audio track in the film is fascinatingly quiet and poorly mixed, as though western life is encapsulated on a soundstage as opposed to the natural sounds of a rural environment. The music itself is so odd and mismatched for the genre, not that it fails completely but it seems to chime in at inopportune moments as opposed to actually assisting the dramatic rhythms of the movie. Understandably though, since there is nothing dramatic happening throughout the entire film, it makes sense that the soundtrack is scattershot.

I opted to watch this film instead of the assigned film for the New Hollywood Class, The Godfather, because I like a good western and was so unfamiliar with Butch Cassidy. In all honesty, I regret this decision in hindsight, even though I’ve seen The Godfather because at least I know I’m going to watch something dynamic happen on screen. Characters are going to change, consequences for actions will happen, the blood that is spilled has a reverence of drama. It’s an iconic film for a reason, to which I say is rightfully deserved opposed to Butch Cassidy, which I’ll mostly forget about once I post this article since there was nothing worth remembering.

*Fuck it, here’s Ebert’s review.

**I think we all know which film used “Raindrops Keep Falling on My Head” the best.