If, as I wrote in last year’s review, that the early 60s were in vogue in 2014, then in 2015 the clock has moved forward to the latter half of the 60s. It seems hardly a coincidence that indie filmmakers would focus on these years: groundbreaking works emerged, as Hollywood was just emerging from its collapse in 1963. Here’s a partial list of films that announced the so-called New Hollywood movement, consisting of independent production companies/studios, was gaining momentum: Seconds (1966), Bonnie and Clyde (1967), Don’t Look Back (1967), Petulia (1968), Easy Rider (1969), Medium Cool (1969), Performance (1970).

A glance at this list not only indicates a wide thematic range, but a willingness to confront the expectations of studio executives: Easy Rider flat-out baffled them; Performance repulsed them. Something significant was going on—the tectonic plates of culture were violently loosened from 1965-70, and remained in insistent motion. Major studios were left reeling from the aftershocks, while the independents were further energized.

Like their predecessors, the three indie filmmakers who had notable releases this year were willing to force Hollywood’s hand. Rather than waiting around for the golden ticket, they went ahead and pushed forward, enlisting some big-name actors in their projects. It sadly must be acknowledged that film making, at all levels, remains rather restrictive in terms of gender, race, and sexual identity—it’s still far more expensive than publishing literature or recording music.

That said, indie films this year opened new spaces for expression, building off of iconic performances in the latter half of the 60s. Make no mistake, this is not mere homage, but, rather, what it means to take the challenge of these years seriously. It means deconstructing and reexamining stereotypes, and exploring shifting points of view. Lastly, it means capturing subtle yet powerful moments of unease that can stand for the widespread unrest of 2015.

Queen of Earth

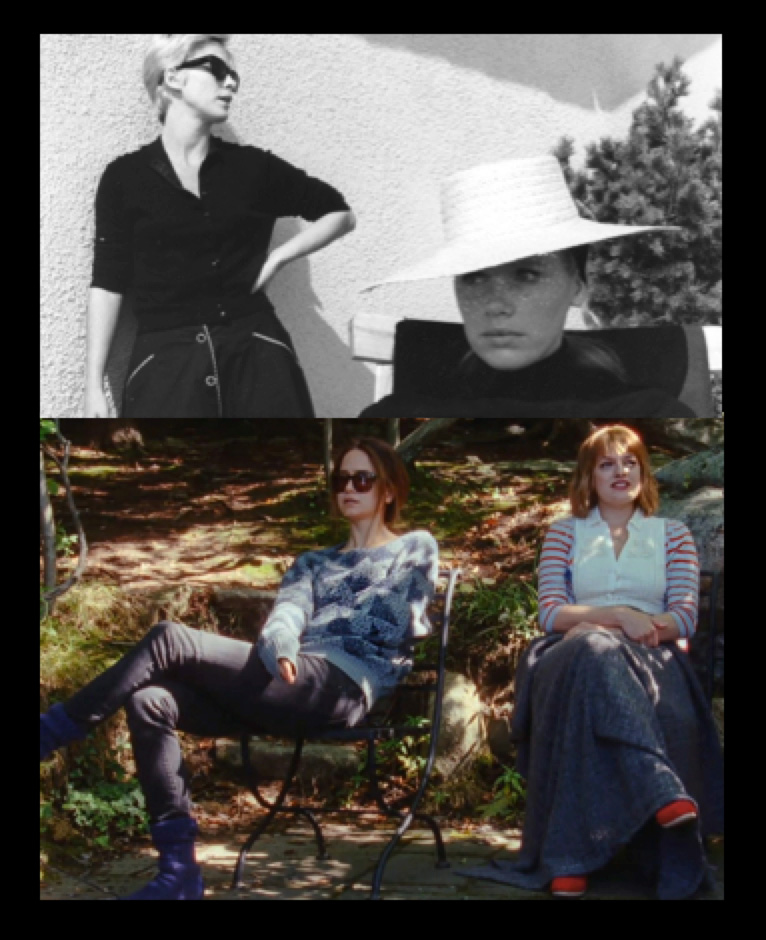

Writer and director Alex Ross Perry appears undaunted in his quest to combine American underground cinema with the cultural cachet of more rigidly psychological European film making that markedly influenced the New Hollywood movement—and to feature two rapidly rising star performers, Elisabeth Moss (from Mad Men and the recent film Perry made, Listen Up Philip) and Katherine Waterston (Inherent Vice). In Queen of Earth, the conflict between two best friends, Catherine (Moss) and Virginia (Waterston) evokes the personality disintegration and blending of a headstrong female patient and youthful nurse in Persona (1966), written and directed by Ingmar Bergman.

Like in Persona, you can feel the chill in the air at the isolated vacation house at the edge of the water. Perry, though, ups the ante by showcasing Moss’s physical violence that shades into her vocal delivery. Whereas the nurse in acting out her repressed frustrations drops a glass that breaks and later injures her patient when she steps on a shard, Catherine throws a cup at Virginia’s obnoxious boyfriend, in retaliation for his territorial aggression. While cleaning up the mess, Virginia cuts her finger—an illustration of the anger and vulnerability that freely passes between them.

Like in Persona, you can feel the chill in the air at the isolated vacation house at the edge of the water. Perry, though, ups the ante by showcasing Moss’s physical violence that shades into her vocal delivery. Whereas the nurse in acting out her repressed frustrations drops a glass that breaks and later injures her patient when she steps on a shard, Catherine throws a cup at Virginia’s obnoxious boyfriend, in retaliation for his territorial aggression. While cleaning up the mess, Virginia cuts her finger—an illustration of the anger and vulnerability that freely passes between them.

We now have seen the casual violence that lies within Catherine. So, when she tells an anonymous guy who she finds passed out in the yard: “You know, I could kill you, and no one would ever know,” she comes across not as awkwardly humorous, but terrifying. If Persona hints at the trauma of Vietnam, Queen of Earth suggests that the social structures designed to limit the exploitation of one person over another are quickly breaking down.

Digging for Fire

Joe Swanberg has long been known in indie circles. His latest film is burdened with the trying-too-hard title, Digging for Fire (you may ask yourself, where is his mind?). Apart from that, however, his writing (getting a co-credit on the film) and directing have made a giant leap forward. Known for slice-of-life portrayals of the post-college crowd, this time he goes to the well for a stronger brew: Faces (1968), written and directed by a pioneer of American independent cinema, John Cassavetes. Originally written as a two-act play, Faces memorably chronicles the separate paths of Richard and Maria, whose marriage is in tatters.

In Digging for Fire, Tim (played by Jake Johnson, who was in a recent film Swanberg made, Drinking Buddies) and Lee, a married couple, show signs of drift. Tim has yet to reach Richard’s lofty status as a CEO; he is, rather, feeling overburdened with a young child whom Lee wants to enroll in an exclusive school they can’t afford—and resents Lee for arranging with her wealthy mother to come up with the necessary funds. Asked by a client of Lee’s to housesit at a posh LA residence creates additional friction. Tim lounges about and puts off doing taxes, while Lee decamps to spend time with her family and a close friend.

What’s interesting is one of the critical relationships in Faces is made more ambiguous in Digging for Fire. The role of the prostitute, Jeannie, whom Richard takes up with is played by Gena Rowlands (married to Cassavetes) in a stunning performance. Tim’s boisterous friend, Ray, played by Sam Rockwell, who chews the scenery in just the right way, seems to “know” quite a few young ladies and brings them to the house for a quasi-bachelor party that night.

One of these ladies, Max, sticks close by Tim’s side. The next day, the belabored digging metaphor finally comes into focus, as Max and Tim work together to excavate the yard where earlier Tim found a bone and a gun. The energetic rhythm of the scene comes off as deliberately goofball as the numerous song and dance routines Jeannie and Richard do together (and, yes, there is a corny pun on “I Dream of Jeannie with the Light Brown Hair”).

One of these ladies, Max, sticks close by Tim’s side. The next day, the belabored digging metaphor finally comes into focus, as Max and Tim work together to excavate the yard where earlier Tim found a bone and a gun. The energetic rhythm of the scene comes off as deliberately goofball as the numerous song and dance routines Jeannie and Richard do together (and, yes, there is a corny pun on “I Dream of Jeannie with the Light Brown Hair”).

Like in Faces, the lighthearted atmosphere gives way to a bleaker environment of masculine competition and mind games—suffice to say, Ray is resentful that Tim gets to spend time with Max. Yet if Richard represents the status quo, then the owners of the mansion in Digging for Fire are absent: an effective way to illustrate how LA epitomizes the national disparity in wealth (that has only worsened since 1968) that has increased to the point where the rich, to those financially strapped, may as well be invisible.

Results

In perhaps the boldest move, Andrew Bujalski reimagines one of the Oscar ceremony’s favorite clips: Jack Nicholson trashing a table at a diner in Five Easy Pieces (1970). This iconic moment is even more fascinating when you realize that the screenwriter, Nicholson’s close friend, modeled this scene on a real-life incident. Yet there is a tendency to overlook what he says afterwards—he didn’t get what he wanted, which serves as an offbeat commentary on how the 60s promise of increased social freedoms were being rolled back during the Nixon era (Hunter S. Thompson, one of Nicholson’s drinking buddies, would have more than strongly agreed).

In perhaps the boldest move, Andrew Bujalski reimagines one of the Oscar ceremony’s favorite clips: Jack Nicholson trashing a table at a diner in Five Easy Pieces (1970). This iconic moment is even more fascinating when you realize that the screenwriter, Nicholson’s close friend, modeled this scene on a real-life incident. Yet there is a tendency to overlook what he says afterwards—he didn’t get what he wanted, which serves as an offbeat commentary on how the 60s promise of increased social freedoms were being rolled back during the Nixon era (Hunter S. Thompson, one of Nicholson’s drinking buddies, would have more than strongly agreed).

In Results, written and directed by Bujalski, a similar scene is the culmination of Cobie Smulder’s no b.s. attitude. Throughout, as the wayward Kat, she has been sparring with Guy Pierce, who plays Trevor, her former boss at a gym—the night before they have rekindled their affair. Now she takes full advantage to berate his passivity when he is overcharged for requesting an omelet without egg yolks. Then she confronts the waitress, and, in a perfect image of her wrecking-ball personality, she slams a heavy training weight on the table.

In Results, written and directed by Bujalski, a similar scene is the culmination of Cobie Smulder’s no b.s. attitude. Throughout, as the wayward Kat, she has been sparring with Guy Pierce, who plays Trevor, her former boss at a gym—the night before they have rekindled their affair. Now she takes full advantage to berate his passivity when he is overcharged for requesting an omelet without egg yolks. Then she confronts the waitress, and, in a perfect image of her wrecking-ball personality, she slams a heavy training weight on the table.

You get the feeling, unlike Nicholson’s character, who ends up exiled in Alaska, she is somehow going to get what she wants. It’s just that she can’t really figure out what she sees in her boss, other than his rugged looks and his dreams of a gym franchise. He goes with the flow; she swims upstream.

Bujalski gets how the drive for business success, in spite of one’s best intentions (Trevor does really want to help his clients lead better lives), empties out a person. Immersed as Trevor is in a very narrow world of physical fitness, he tends to overlook the differences in personal philosophies, in favor of a more bureaucratic attitude of health management. This, however, does not prevent him from getting the short end of a business deal. It reminds us that corporate interests have long been interested in healthcare issues—which promises to be a major issue in the next election, regardless of the probable lack of media attention.