Who Shot It: Vilmos Zsigmond. In the 1970s, there was a group of cinematographers who pretty much singlehandedly decided the look of films in that decade. Zsigmond was part of that group. A native Hungarian, he became friends with fellow future 70s cinematographic pioneer Laszlo Kovacs and together, they shot footage of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, which led them to have to escape, first to Austria, and later to America. In his first decade of working in America, Zsigmond pretty much exclusively worked on, and there’s no nice way to put this, trash (if you find yourself watching The Incredibly Strange Creatures Who Stopped Living and Became Mixed-Up Zombies, remind yourself that it was shot by the same guy who shot Close Encounters of the Third Kind). But as the 70s started, Zsigmond got a big break in the form of Robert Altman, who asked him to shoot his 1971 revisionist western McCabe and Mrs. Miller, now regarded as one of the most beautiful films of the 70s, and maybe of all-time. There, Zsigmond pioneered the technique of “flashing”, where the negative is exposed to a predetermined amount of light before it’s printed, bringing out more light in the blacks, creating a brighter, foggier image. Zsigmond would reuse this technique on his two other films with Altman, the psychological drama Images and the unorthodox Chandler adaptation The Long Goodbye, where the flashing gives the film’s 70s L.A. setting the feeling of being ever-so-slightly out of time. His legacy would be secure if his work ended there, but oh boy, it didn’t. During this time, he hooked up with a young upstart by the name of Steven Spielberg, whom he worked with on The Sugarland Express and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, the latter winning him an Oscar. He shot the Palme d’Or winner Scarecrow, the Best Picture winner The Deer Hunter, and the Best Picture nominee Deliverance. He worked on Mark Rydell’s The Rose with almost all of his fellow great 70s cinematographers, including Kovacs, Conrad Hall, Haskell Wexler, and Owen Roizman, and on Martin Scorsese’s The Last Waltz, with Kovacs and almost of the remaining great 70s cinematographers. But as he went into the 80s, his filmography became dicier. It didn’t help that he started the decade with the mega-flop that’s often cited as the death of New Hollywood, Heaven’s Gate, even though time has been much kinder to it than its initial reviews would have one believe (it helped that it looks jaw-droppingly gorgeous). From there, he worked on Brian De Palma (his collaborator on 1976’s Obsession)’s Blow Out (a classic now that was ignored at the time), a good comedy, Real Genius, mixed with bad comedies, Jinxed and No Small Affair, and another troubled production, George Miller’s The Witches of Eastwick (which is probably the most overlooked film in Miller’s filmography despite the Zsigmond factor). The 90s saw him stuck on even more sinking ships, lighting and framing as well as he possibly could, including De Palma’s The Bonfire of the Vanities, The Two Jakes, Intersection, Assassins, The Ghost and the Darkness, and Sliver. One could count the number of good films he graced with his talent in that decade on one hand, those being Richard Donner’s Maverick and Sean Penn’s The Crossing Guard. I wish I could say his 2000s was better, but alas, it was probably worse. His highest-profile gigs during this period were another De Palma flop (that’s gotten a bit of a reevaluation since), The Black Dahlia (the source of his final Oscar nomination), his two films for Woody Allen (his third, You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger, came out in 2010), Melinda and Melinda and the insanely underrated Cassandra’s Dream, and the Irwin Winkler tearjerker Life as a House. He had even less going on in the 2010s, although he did get to shoot more than 20 episodes of The Mindy Project. He died on New Year’s Day, 2016, leaving behind a body of work that may be spotty (incredibly spotty) in quality, but is consistent in terms of beauty. So let’s celebrate his work by looking at a film he made for a director who only recently went beyond baseline competence stylistically.

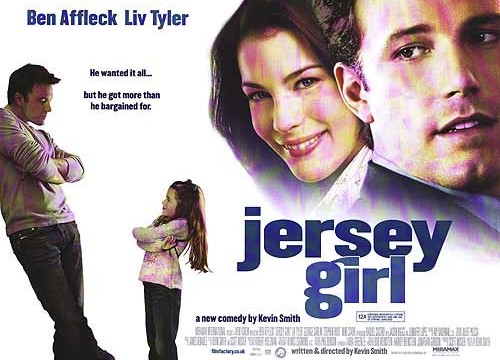

What Do You Mean, Story?: I don’t hate Kevin Smith. I like many of his movies. Hell, I’m an avowed fan of Mallrats despite half of the leads in that movie being garbage. But let’s just say that I’m not rushing out to his defense after this past decade, where he’s alternated between following whatever minor creative successes he’s had (which, of course, flop) with retreats back into his comfort zone, bashing critics, making and breaking promises seemingly on a daily basis, getting into fights with airlines, not realizing that “Wouldn’t it be funny if…” is never a good start for the making of a movie, making viewers have to fight to get to Rosario Dawson dancing to the Jackson 5, and threatening America with sequels to movies that were perfectly fine without them. And all that is thanks to one little film; Jersey Girl. After Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back seemed to close out Smith’s “View Askewniverse” films for good, he decided to branch out, and make something that people beyond his devoted fanbase could enjoy, a romantic comedy that still managed to keep his personality. The result was that he got the worst reviews of his career up to that point, and it didn’t really set the box office on fire either. So, with the whole “trying new things” idea thrown out the window, he went back to the safety of Clerks, and the rest is sad, sad history. But is the film that led him down this sorry path really that bad? Not really…ish?

The movie starts out relatively Smithian, at least. The opening follows the can’t-miss formula of children saying things whose meaning goes completely over their heads, with a class giving presentations about their families (one kid believes his parents to be religious, because whenever they go to bed, he hears them yell “JESUS!!!”). It’s not comedic gold, but it doesn’t make the viewer want to slit their wrists either (I want to go back in time and demand that Harvey Weinstein put that on the poster). And then after all that, a young girl steps up to present, and she tells us the story of her family, the story of the film.

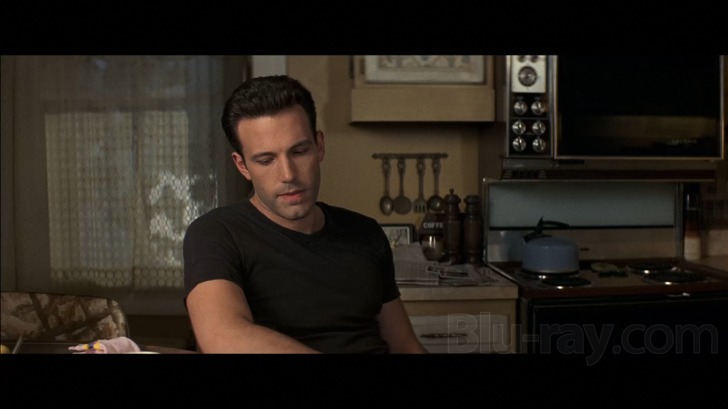

A few entries ago, I covered the drama Regarding Henry, about an asshole businessman who’s humbled by a bullet to the brain. Ollie Trinke (Ben Affleck, when he was at maximum insufferability) may not get shot in this movie, but the message is essentially the same. He’s a slick, fast-talking PR guy for superstar musicians, and since he has the job during the 90s, he can allow for Smith to make jokes like the one about how George Michael can’t be gay, he’s an alpha-male, hardy har har. He soon meets a woman named Gertrude (Jennifer Lopez, when she was at maximum insufferability), and since this came out in the wake of Gigli, their romance is sped through like Smith was on crack during his stay in the editing room. They get married (not seen, although it was shot and exists in an extended cut Smith keeps promising to release), and she becomes pregnant, but immediately after delivery, she suffers an aneurysm and dies. In shock, but still wanting to get back to work (boo!!!!), Ollie moves back in with his father (George Carlin, adding much-needed warmth and honesty to what could have been the stock “crotchety grandpa” role) and leaves him to take care of his daughter (boooo!!!!!!!!) while he handles PR for Will Smith, who he doesn’t believe will go anywhere, hardy har har. But, in the words of Roger from American Dad, his ignorance this time around isn’t a wink to the audience, it’s a major plot point, as, frustrated when he has to take his daughter to the press conference, he loses his job because he tells everyone in the audience that Will Smith is a nobody who’s going to peter out. He then goes back home (to the strains of “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot”, which is on the Zemeckis end of what I deem the “Zemeckis-Haneke Continuum” for obvious music cues), and raises his daughter, named after Gertrude in his dad’s house, while biding his time doing jobs as a street-sweeper and garbageman. The movie picks up when his daughter is seven, when he meets a spunky, obsessed-with-spunk grad student video clerk named Maya (Liv Tyler). Later, they attempt to bone, but are driven into the shower by Gertie. When Ollie gets a big job offer in the City, he has to decide between family and okay, serious question here; has there ever been one of these type of family comedies about a dad deciding between family and work, and choosing work? I kinda want that movie to be made now.

I don’t hate Jersey Girl. There, I said it. I don’t hate it. In fact, I found it to be perfectly pleasant (of course, pleasant is only slightly above “it didn’t make me slit my wrists” in terms of back-handed compliments). The movie’s biggest problem is that it’s ultimately defeated by the requisite family rom-com stuff Smith has to include. Yes, Ollie will get out of his meeting with the PR giant after encouragement from a special celebrity guest star (I know what you’re thinking, and yes, that special celebrity guest star is Joaquin Phoenix), and yes, despite literal roadblocks (of his own creation, no less), he will make it to Gertie’s talent show performance. The fact that her performance is the only one in the show that isn’t “Memories” from Cats or that the thing she’s performing is fucking Sweeney Todd helps, but the fact that Smith is unironically indulging in these cliches in the first place is bad enough to still be a serious problem. And almost as big a problem is that Smith can (could?) do comedy of all stripes, but he can’t do treacle, and he has to go to that well far too many times here (although the end dedication to his father suggests that the treacle was the reason he went to this well in the first place). But there are good portions of the film, where the characters are just shooting the shit (there were probably more of them in that extended cut), that are reasonably fun to watch, and they’re ultimately my big takeaways from the film. Sure, the humor does get too cutesy at times (see: Ollie confronting his daughter and a friend about not showing each other their genitals, followed later by Gertie giving the same talk about Ollie and Maya’s aborted boning), but it’s really inoffensive at worst, and genuinely amusing at best (I especially enjoyed Stephen Root’s performance as one of Carlin’s work buddies who’s this movie’s version of Chris Rock’s sidekick in Pootie Tang). Maybe I’ve just been so burnt out on the last few films I’ve reviewed that something harmless like this comes off as a breath of fresh air. At least this isn’t about goddamn snuff films.

Screw That, Let’s Talk Pretty Pictures: This is going to be a more interesting edition of this segment than normal. As suggested by the hilarious incongruity of having the guy who shot McCabe and Mrs. Miller shoot a movie for goddamn Kevin Smith, this movie’s cinematography seems at war with itself. Normally, I wouldn’t suggest that a film looking good is entirely the result of the DoP, but here, judging by Smith’s immediately post-movie blog post on it (where he has a temper tantrum at Zsigmond) and a much more recent podcast interview on it (where he admits that his whining was a result of him not wanting to be pushed out of his comfort zone, which he now thanks Zsigmond for doing), I can safely assume that Smith had nothing to do with this film’s good shots, and fought to keep them out of the movie. You can tell what shots Smith was more comfortable making; the shots of just people talking, which are almost all visually unremarkable static close-ups or medium shots. And you can tell when Zsigmond pushed Smith; those are generally the wider shots where the camera actually, you know, moves (there are even scenes whose effect is determined by how the camera moves, such as a shaky tracking shot following Ollie as he runs to the door of the auditorium where the talent show is held). And also the shots where the lighting is anything besides functional (like Ollie in a red-lit parking garage immediately after his firing). Quite frankly, if this was for any other director, I’d find Zsigmond’s work here to be horribly disappointing, as even the standout shots have been done before. But I have to grade on a curve here, and the fact that I found any of the shots in a Kevin Smith movie to be particularly meaningful or well-composed beyond their relationship to his dialogue is remarkable enough to give this movie’s cinematography a passing grade.

Favorite Shot/Sequence: Here’s another sequence where movement is instrumental to its effect; the sequence where Gertrude gives birth and dies in short order. It’s all shot handheld, but it starts relatively peaceful before all hell breaks loose in the hospital room and the camera becomes apocalyptically shaky.

Is It Worth Watching: Eh, sure.

Stray Observations:

- I wanted to mention this in the main review, but opted against it; this is our very own Hooded Justice’s screen debut! He’s behind Ben Affleck and the kid when they’re about to see a Broadway show. He would’ve been in the sequence where they actually see the show, but apparently Smith shot down Zsigmond’s suggestion to film the scene in a wider shot. I’ll probably forget what I had for dinner tonight by tomorrow morning, but this information will be in there forever.

- YOU KNOW WHAT??? THERE IS NO EASTER BUNNY!!!!! OVER THERE, THAT’S JUST A GUY IN A SUIT!!!!!!!

Up Next: The world’s first combo government cover-up thriller/Robin Williams comedy.