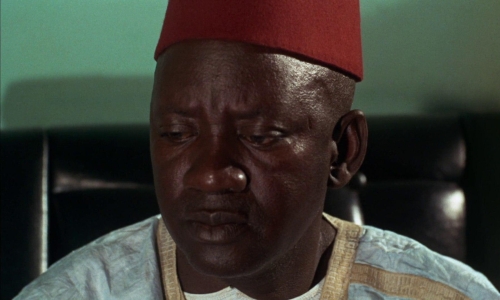

Ousmane Sembène’s 1968 film Mandabi is an uncomfortable, queasy pleasure. The film’s action kicks off with the arrival of a money order addressed to the unemployed–but vainglorious–Ibrahima (Makhourédia Guève); his wives, Aram (Isseu Niang) and Méty (Ynousse N’Diaye) know about it before he does and promptly spin its existence into new lines of credit with everyone in town. Ibrahima complains about them spreading the news–especially since it means he now attracts beggars and needy friends wheedling him for loans–but he’s hardly restrained himself. Who can blame them? The mere existence of the money order waiting in the post office is a ticket to the simple pleasures they’re all routinely denied. One of their biggest expenditures is a stockpile of rice, so it’s not like they’re blowing their windfall on luxuries. They have kids to feed.

But is the money order a windfall at all? Not really, not in this acerbic, tragicomic farce. For one thing, Ibrahima has vastly overestimated how much of the 25,000 francs are his–he can’t read his nephew’s letter, so it takes him days to learn that he’s only a temporary steward of the lion’s share. The nephew, a street-sweeper in Paris, wants to use it to build up his own savings so he can come back someday and get married; another portion, he writes, will go to his mother. Ibrahima gets a kind of token finder’s fee for handling it all, 2,000 francs, just because his nephew knows he’s going through hard times and is throwing him a bone. By the time Ibrahima knows how much he’s actually entitled to, he’s essentially already spent it, and that’s before he has to shell out for bribes and governmental fees. It’s before he gets conned. He doesn’t have the necessary papers or connections to pick up the money order right away, and the whole bureaucratic process grinds him down and bleeds him dry. (It doesn’t help that beneath all his bluster he’s ultimately naive: too quick to trust and too slow to lie.)

The repetitious, circular process Ibrahima goes through and the periodic sessions of meeting back up with his neighbors to rehash it all make the film feel slightly too long. And while he’s well-realized–a man with a comedic temperament caught in a building tragedy–some of the more broadly sketched characters around him don’t work quite as well.

However, when Mandabi is at its best and most energetic, it’s a kind of offhanded, breezy crime film, where corruption is as routine as breath and even the photography studio is out to get you. This is, I think, the mode of the film that best suits its bright visuals and confident direction, which do a fantastic job implicitly contrasting the solid, flesh-and-blood positives–a thorough shave, a good meal, a leg massage, soaking sore feet–with all the amorphous evils that snare Ibrahima like a web–bureaucracy, rumors, schemes, malice, the lingering impact of colonialism. From this angle, the movie makes an enticingly beautiful pitcher plant with a deadly trap of an ending.

Mandabi is streaming on the Criterion Channel.